Embioptera

The order Embioptera, commonly known as webspinners or footspinners,[2] are a small group of mostly tropical and subtropical insects, classified under the subclass Pterygota.

[5] The common name webspinner comes from the insects' unique tarsi on their front legs, which produce multiple strands of silk.

[9] Species such as Atmetoclothoda orthotenes, possibly the first fossil member of the Clothodidae to be discovered, sometimes thought to be a "primitive" family, have been found in mid-Cretaceous amber from northern Myanmar.

[14][15] The position of the Embioptera within the Polyneoptera suggested by a phylogenetic analysis carried out in 2012 by Miller et al., combining morphological and molecular evidence, is shown in the cladogram.

[1] Plecoptera (stoneflies) Dictyoptera (cockroaches, mantises) Orthoptera (grasshoppers, crickets) Phasmatodea (stick insects) Embioptera (webspinners) The internal phylogeny of the group is not yet fully resolved.

Four families were found to be robustly monophyletic in whatever way the phylogeny was analysed (parsimony, maximum likelihood, or Bayesian): Clothodidae, Anisembiidae, Oligotomidae, and Teratembiidae.

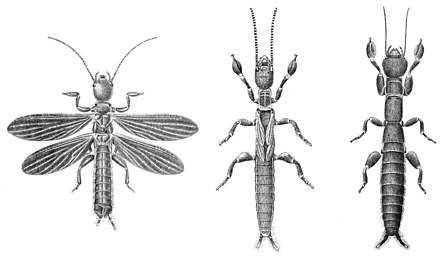

The body form of these insects is completely specialised for the silk tunnels and chambers in which they reside, being cylindrical, long, narrow and highly flexible.

[19] In both males and females the legs are short and sturdy, with an enlarged basal tarsomere on the front pair, containing the silk-producing glands; the mid and hind legs also have three tarsal segments with the hind femur enlarged to house the strong tibial depressor muscles that enable rapid reverse movement.

For this reason, the main form of taxonomic identification used in the past has been close observation of distinctive copulatory structures of males, (although this method is now thought by some entomologists and taxonomists as giving insufficient classification detail).

After a short period of parental care, the nymphs undergo hemimetabolosis (incomplete metamorphosis), moulting a total of four times before reaching adult form.

This phenomenon occurs when a female is, for whatever reason, unable to find a male to mate with, thus giving her and her species reproductive security at all times.

[8] At this time the adult females become very territorial and aggressive to other individuals with whom they previously lived in harmony; three different types of vibratory signals are used to deter other embiopterans that approach the eggs too closely, and the intruder usually retires.

[24] The parthenogenetic Rhagadochir virgo incorporates scraps of lichen into the silk wrapping the eggs, and this may be eaten by newly hatched nymphs.

Even in species that provide no further parental care, the nymphs in the colony benefit from the greater silk-producing power of the adults and the extra protection that the more copious silk covering brings.

[8] Subsociality is a trade-off for the female, as the energy and time that is exerted in caring for her young is rewarded by giving them a much greater chance of surviving and carrying on her genetic lineage.

[26] When constructing their silken galleries, webspinners use characteristic cyclic movements of their forelegs, alternating actions with the left and right legs while also moving.

The galleries are essential to their life cycle, maintaining moisture in their environment, and also offering protection from predators and the elements while foraging, breeding and simply existing.

The insects spin silk by moving their forelegs back and forth over the substrate, and rotating their bodies to create a cylindrical, silk-lined tunnel.

Each gallery complex contains several individuals, often descended from a single female, and forms a maze-like structure, extending from a secure retreat into whatever vegetable food matter is available nearby.

They are generalist herbivores; during his research, Ross maintained a number of species in the laboratory on a diet of lettuce and dry oak leaves.

A Neotropical tachinid fly, Perumyia embiaphaga,[32] and a braconid wasp species in the genus Sericobracon,[33] are known to be parasitoids of adult embioptera.

[6] Embiopterans are distributed worldwide, and are found on every continent except Antarctica, with the highest density and diversity of species being in tropical regions.

Others live out in the open, either swathed in sheets of white or blue silk, or hidden in less-conspicuous silken tubes, on the ground, on the trunks of trees or on the surface of granite rocks.

[6] They were absent from Britain until 2019, when Aposthonia ceylonica, a southeast Asian species, was found in a glasshouse at the RHS Garden, Wisley.