Weimar Constitution

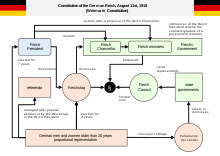

The constitution created a federal semi-presidential republic with a parliament whose lower house, the Reichstag, was elected by universal suffrage using proportional representation.

The president of Germany had supreme command over the military, extensive emergency powers, and appointed and removed the chancellor, who was responsible to the Reichstag.

Although it was de facto set aside by the Enabling Act of 1933, the constitution remained legal-technically in effect throughout the Nazi era from 1933 to 1945 and also during the Allied occupation of Germany from 1945 to 1949.

The victorious parties, led by Friedrich Ebert of the Social Democrats (SPD), scheduled an election on 19 January 1919 – in which women for the first time had equal voting rights with men[1] – for a national assembly that was to act as Germany's interim parliament and draft a new constitution.

Ebert wanted the victorious Allies to be reminded of Weimar Classicism, which included the writers Goethe and Schiller, while they were deliberating the terms of the Versailles Treaty.

[4] He based his draft in large part on the Frankfurt Constitution of 1849 which was written after the German revolutions of 1848–1849 and intended for a unified Germany that did not come to pass at the time.

He was influenced as well by Robert Redslob's theory of parliamentarianism, which called for a balance between the executive and legislative branches under either a monarch or the people as sovereign.

[5] During July 1919, the National Assembly moved quickly through the draft constitution with most debates concluded within a single session and without public discussion of the issues.

(Germany received the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, which reduced its land area and population by 13% and 12% respectively, on 7 May 1919, while the constitution was being debated in the National Assembly.

Each state parliament (Landtag) was to be elected by equal, secret, direct and universal (both men and women) ballot according to the principles of proportional representation.

Members of the Reichstag and of the state parliaments were immune from arrest or investigation of a criminal offense except with the approval of the legislative body to which the person belonged.

Article 48 gave the president the power to take measures – including the use of armed force and/or the suspension of civil rights – to restore law and order in the event of a serious threat to public safety or security.

In 1933 President Paul von Hindenburg and Chancellor Adolf Hitler, using Article 48 as the basis for the Reichstag Fire Decree, legally swept away most of the key the civil liberties granted in the Weimar Constitution and thereby facilitated the establishment of a dictatorship.

Under the Weimar Constitution, the vote of no confidence often resulted in difficulty forming new coalitions and a degree of parliamentary instability that in the end was fatal to the Republic.

The Reichstag could accuse the president, chancellor, or any minister of willful violation of the constitution or Reich law, with the case to be tried in the Supreme Judicial Court.

Hugo Preuss publicly criticised the Triple Entente's decision in the Treaty of Versailles to prohibit the unification of "Greater Germany", saying that it was a contradiction of the Wilsonian principle of the self-determination of peoples.

If the Reichstag voted to overrule the Reichsrat's objection by a two-thirds majority, the Reich president was obligated to either proclaim the law into force or to call for a referendum.

In cases where legislation had yet to be passed (such as the laws governing the new Supreme Judicial Court), the articles stipulated how the constitutional authority would be exercised in the interim by existing institutions.

In his book The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, historian William L. Shirer described the Weimar Constitution as "on paper, the most liberal and democratic document of its kind the twentieth century had ever seen ... full of ingenious and admirable devices which seemed to guarantee the working of an almost flawless democracy.

In addition, there was no public debate on the decisions the National Assembly took on issues with serious long-term consequences, with the result that "the sovereign people once again proved to be a useful fiction for legitimacy".

Article 48, the so-called emergency decree provision, gave the president broad powers to suspend civil liberties, with the checks and balances in it proving in practice to be insufficient.

[26][27] Although the original intent was that Article 48 would be used sparingly to restore constitutional order in the event of a national emergency, it was invoked 205 times before Adolf Hitler became chancellor.

The system, intended to avoid the wasting of votes, allowed the rise of a multitude of parties which made it difficult for any of them to establish and maintain a workable parliamentary majority.

[32] In the early days of the German revolution, the moderate leadership of the Council of the People's Deputies decided that for the sake of stability it was better to keep the large bureaucratic machinery of the Empire than to attempt to replace thousands of experienced officials, the majority of whom remained loyal to the monarchy.

When the Weimar Constitution was being written, the powerful German Civil Service Federation (Deutscher Beamtenbund) was able to exert pressure to add special protections for government officials in Articles 128 to 131, even though Preuss had had no intention of including such language.

In addition to liberal provisions that granted freedom of political opinion, the articles guaranteed professional government officials life appointments and old age and survivors' benefits.

This special inclusion in the constitution proved to be a considerable problem for the Republic in that it made it difficult for bureaucratic reforms to remove the many opponents of democracy in high-ranking positions, especially the judiciary.

Article 2 of the Act stated that "laws enacted by the government of the Reich may deviate from the constitution as long as they do not affect the institutions of the Reichstag and the Reichsrat.

In the final three Reichstag elections held during his rule (November 1933, March 1936 and April 1938), voters were presented with a single list of Nazis and "guest candidates".

He named Dönitz president, not Führer, thereby re-establishing a constitutional office which had lain dormant since Hindenburg's death ten years earlier.