Weimar culture

Leading Jewish intellectuals on university faculties included physicist Albert Einstein; sociologists Karl Mannheim, Erich Fromm, Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse; philosophers Ernst Cassirer and Edmund Husserl; political theorists Arthur Rosenberg and Gustav Meyer; and many others.

By 1919, an influx of labor had migrated to Berlin turning it into a fertile ground for the modern arts and sciences, leading to booms in trade, communications and construction.

The Wilhelminian values were further discredited as a consequence of World War I and the subsequent inflation, since the new youth generation saw no point in saving for marriage in such conditions, and preferred instead to spend and enjoy.

The most prominent philosophers with which the so-called 'Frankfurt School' is associated were Erich Fromm, Herbert Marcuse, Theodor Adorno, Walter Benjamin, Jürgen Habermas and Max Horkheimer.

German artists made multiple cultural contributions in the fields of literature, art, architecture, music, dance, drama, and the new medium of the motion picture.

Artists gravitating towards this aesthetic defined themselves by rejecting the themes of expressionism—romanticism, fantasy, subjectivity, raw emotion and impulse—and focused instead on precision, deliberateness, and depicting the factual and the real.

Kirkus Reviews remarked upon how much Weimar art was political:[13] fiercely experimental, iconoclastic and left-leaning, spiritually hostile to big business and bourgeois society and at daggers drawn with Prussian militarism and authoritarianism.

This organization was established in the aftermath of the November beginning of the German Revolution of 1918–1919, when communists, anarchists and pro-republic supporters fought in the streets for control of the government.

The group also had chapters throughout Germany during its existence, and brought the German avant-garde art scene to world attention by holding exhibits in Rome, Moscow and Japan.

Its members also belonged to other art movements and groups during the Weimar Republic era, such as architect Walter Gropius (founder of Bauhaus), and Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht (agitprop theatre).

German Expressionism had begun before World War I and continued to have a strong influence throughout the 1920s, although artists were increasingly likely to position themselves in opposition to expressionist tendencies as the decade went on.

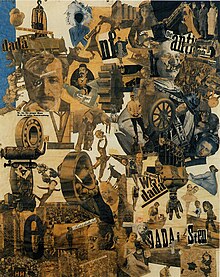

In Germany, Richard Huelsenbeck established the Berlin group, whose members included Jean Arp, John Heartfield, Wieland Hertzfelde, Johannes Baader, Raoul Hausmann, George Grosz and Hannah Höch.

Broadly speaking, artists linked with New Objectivity include Käthe Kollwitz, Otto Dix, Max Beckmann, George Grosz, John Heartfield, Conrad Felixmüller, Christian Schad, and Rudolf Schlichter, who all "worked in different styles, but shared many themes: the horrors of war, social hypocrisy and moral decadence, the plight of the poor and the rise of Nazism".

While their art is recognizable as a bitter, cynical criticism of life in Weimar Germany, they were striving to portray a sense of realism that they saw missing from expressionist works.

The founders intended to fuse the arts and crafts with the practical demands of industrial design, to create works reflecting the New Objectivity aesthetic in Weimar Germany.

The mass housing projects of Ernst May and Bruno Taut are evidence of markedly creative designs being incorporated as a major feature of new planned communities.

Erich Mendelsohn and Hans Poelzig are other prominent Bauhaus architects, while Mies van der Rohe is noted for his architecture and his industrial and household furnishing designs.

Writers such as Alfred Döblin, Erich Maria Remarque and the brothers Heinrich and Thomas Mann presented a bleak look at the world and the failure of politics and society through literature.

[8] Eastern religions such as Buddhism were becoming more accessible in Berlin during the era, as Indian and East Asian musicians, dancers, and even visiting monks came to Europe.

Cultural critic Karl Kraus, with his brilliantly controversial magazine Die Fackel, advanced the field of satirical journalism, becoming the literary and political conscience of this era.

[23] Other authors of such material include Klaus Mann, Anna Elisabet Weirauch, Christa Winsloe, Erich Ebermayer, and Max René Hesse.

[24][25][26] The theatres of Berlin and Frankfurt am Main were graced with drama by Ernst Toller, Bertolt Brecht, cabaret, and stage direction by Max Reinhardt and Erwin Piscator.

Its aim was to add elements of public protest (agitation) and persuasive politics (propaganda) to the theatre, in the hope of creating a more activist audience.

The sets depict distorted, warped-looking buildings in a German town, while the plot centres around a mysterious, magical cabinet that has a clear association with a casket.

[32] The Blue Angel (1930), directed by Josef von Sternberg with the leads played by Marlene Dietrich and Emil Jannings, was filmed simultaneously in English and German (a different supporting cast was used for each version).

Diary of a Lost Girl (1929) directed by Georg Wilhelm Pabst and starring Louise Brooks, deals with a young woman who is thrown out of her home after having an illegitimate child, and is then forced to become a prostitute to survive.

In 1919, Richard Oswald directed and released two films, that met with press controversy and action from police vice investigators and government censors.

[41] Aufklärungsfilme (enlightenment films) supported the idea of teaching the public about important social problems, such as alcohol and drug addiction, venereal disease, homosexuality, prostitution, and prison reform.

Publishers met this demand with inexpensive criminal novels called Krimi, which like the film noir of the era (such as the classic M), explored methods of scientific detection and psychosexual analysis.

[49] Apart from the new tolerance for behaviour that was technically still illegal, and viewed by a large part of society as immoral, there were other developments in Berlin culture that shocked many visitors to the city.