Weingut I

Weingut I (English: Vineyard I) was the codename for a construction project, begun in 1944, to create an underground factory complex in the Mühldorfer Hart [de] forest, near Mühldorf am Inn in Upper Bavaria, Germany.

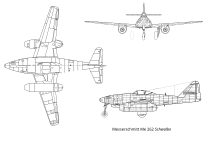

Plans for the bunker called for a massive reinforced concrete barrel vault composed of 12 arch sections under which Messerschmitt Me 262 jet engines would be manufactured in a nine-storey factory.

Upon completion these were to be sent to a similar installation in the area of Landsberg am Lech (codename Weingut II), where the final assembly of the aircraft was to take place.

This network of underground factories was intended to ensure the production of the Me 262 at a time when the Allies had already gained control of the German airspace.

[1] Despite it being increasingly clear to the organizers of the project that it would never be finished in time to make a difference in the war,[2] the construction of Weingut I was approved on a 6-month timeline.

In early 1944, the Allied air war began to focus primarily upon the destruction of the Luftwaffe in preparation for the invasion of Normandy.

Plans for the so-called "Big Week", which was intended to permanently smash the German capacity to produce fighter aircraft through targeted airstrikes on final assembly factories, were already underway in 1943.

At the head of the Jägerstab was armaments minister Albert Speer, as Deputy the Secretary of State Erhard Milch, as Chief of Staff Karl Saur.

Their plan to protect the aircraft industry, especially the manufacture of the jet-powered Messerschmitt Me 262, entailed the relocation of assembly plants into underground bunkers.

Strategically the important railway juncture of Mühldorf was advantageous, and the wide-ranging forest of the Mühldorfer Hart would offer excellent camouflage for the completed bunker.

Besides these additional smaller bunkers intended to serve as air raid shelters were erected before construction on the main site began.

[17] Upon completion the entire bunker was to be covered with soil and planted over with trees and bushes, but considering the scale of the project it was hardly possible to effectively camouflage it from aerial reconnaissance during the construction process.

Indeed, the site was hard to miss, and the USAF took several aerial photos of it in February 1945 during reconnaissance prior to the bombardment of the airfield at Mettenheim and the train yard at Mühldorf.

The site was discovered upon examination of the photos, as an overhead view of main bunker drawn in March 1945 and labeled "MUHLDORF (GERMANY) SEMI-BURIED INSTALLATION" attests.

First an underground "extraction tunnel", fitted with a single train track and a gated roof, was built along the entire length of the planned bunker.

[21] When the 47th tank battalion of the 14th Armored Division reached Mühldorf in the early days of May 1945, the construction area and all related facilities were placed under US military administration.

Next the army decided to use the grounds as a bomb test site in order to determine the effectiveness of the bunker:[22] It is recommended that the U.S. Army avail itself of the opportunity to test the resistance of this type of construction by actually subjecting one of the arches to a full scale bombing… Test bombing is recommended because: (1) This type of construction might be adopted for war-time industrial installations in the United States or its possessions, and; (2) this uncompleted building with little or no future utility provides a rare opportunity to conduct a full-scale bombing test.This proposal was accepted and in the summer of 1947 the command for the demolition was issued.

[24] The ruins of the bunker complex can still be seen in the woods near Mettenheim, although much material from the site has been scavenged in the intervening years by local companies for other building projects.

The grounds entered the public eye again in the 1980s, when rumors began to circulate that chemical agents of the Wehrmacht had been stored in the tunnels of the complex after the war.

[25] In 1992, the Bundesvermögensverwaltung (Federal Property Administration, an agency that has since been superseded by the Bundesanstalt für Immobilienaufgaben) proposed to demolish the bunker.