Life-cycle assessment

The aim is to document and improve the overall environmental profile of the product[2] by serving as a holistic baseline upon which carbon footprints can be accurately compared.

The general categories of environmental impacts needing consideration include resource use, human health, and ecological consequences.Criticisms have been leveled against the LCA approach, both in general and with regard to specific cases (e.g., in the consistency of the methodology, the difficulty in performing, the cost in performing, revealing of intellectual property, and the understanding of system boundaries).

When the understood methodology of performing an LCA is not followed, it can be completed based on a practitioner's views or the economic and political incentives of the sponsoring entity (an issue plaguing all known data-gathering practices).

[7][1][8] Also, due to the general nature of an LCA study of examining the life cycle impacts from raw material extraction (cradle) through disposal (grave), it is sometimes referred to as "cradle-to-grave analysis".

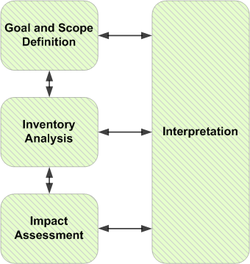

[6] As stated by the National Risk Management Research Laboratory of the EPA, "LCA is a technique to assess the environmental aspects and potential impacts associated with a product, process, or service, by: Hence, it is a technique to assess environmental impacts associated with all the stages of a product's life from raw material extraction through materials processing, manufacture, distribution, use, repair and maintenance, and disposal or recycling.

[14] Consequential LCAs seek to identify the environmental consequences of a decision or a proposed change in a system under study, and thus are oriented to the future and require that market and economic implications must be taken into account.

[14] In other words, Attributional LCA "attempts to answer 'how are things (i.e. pollutants, resources, and exchanges among processes) flowing within the chosen temporal window?

Items on the questionnaire to be recorded may include: Oftentimes, the collection of primary data may be difficult and deemed proprietary or confidential by the owner.

[45] EIOLCA is a top-down approach to LCI and uses information on elementary flows associated with one unit of economic activity across different sectors.

This phase of LCA is aimed at evaluating the potential environmental and human health impacts resulting from the elementary flows determined in the LCI.

This is accomplished by identifying the data elements that contribute significantly to each impact category, evaluating the sensitivity of these significant data elements, assessing the completeness and consistency of the study, and drawing conclusions and recommendations based on a clear understanding of how the LCA was conducted and the results were developed.

Curran, the goal of the LCA interpretation phase is to identify the alternative that has the least cradle-to-grave environmental negative impact on land, sea, and air resources.

They are used in the built environment as a tool for experts in the industry to compose whole building life cycle assessments more easily, as the environmental impact of individual products are known.

[75] Moreover, time horizon is a sensitive parameter and was shown to introduce inadvertent bias by providing one perspective on the outcome of LCA, when comparing the toxicity potential between petrochemicals and biopolymers for instance.

[83] Cradle-to-grave is the full life cycle assessment from resource extraction ('cradle'), to manufacturing, usage, and maintenance, all the way through to its disposal phase ('grave').

[85] Cradle-to-gate is an assessment of a partial product life cycle from resource extraction (cradle) to the factory gate (i.e., before it is transported to the consumer).

They can then add the steps involved in their transport to plant and manufacture process to more easily produce their own cradle-to-gate values for their products.

[86] Cradle-to-cradle is a specific kind of cradle-to-grave assessment, where the end-of-life disposal step for the product is a recycling process.

The Greenhouse gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy use in Transportation (GREET) model was developed to evaluate the impacts of new fuels and vehicle technologies.

The model reports energy use, greenhouse gas emissions, and six additional pollutants: volatile organic compounds (VOCs), carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen oxide (NOx), particulate matter with size smaller than 10 micrometer (PM10), particulate matter with size smaller than 2.5 micrometer (PM2.5), and sulfur oxides (SOx).

It was designed to provide a guide to wise management of human activities by understanding the direct and indirect impacts on ecological resources and surrounding ecosystems.

Developed by Ohio State University Center for resilience, Eco-LCA is a methodology that quantitatively takes into account regulating and supporting services during the life cycle of economic goods and products.

[105] This intuition confirmed by DeWulf[106] and Sciubba[107] lead to Exergo-economic accounting[108] and to methods specifically dedicated to LCA such as Exergetic material input per unit of service (EMIPS).

Work has been undertaken in the UK to determine the life cycle energy (alongside full LCA) impacts of a number of renewable technologies.

[119] While incineration produces more greenhouse gas emissions than landfills, the waste plants are well-fitted with regulated pollution control equipment to minimize this negative impact.

[120] Energy efficiency is arguably only one consideration in deciding which alternative process to employ, and should not be elevated as the only criterion for determining environmental acceptability.

A 2022 dataset provided standardized calculated detailed environmental impacts of >57,000 food products in supermarkets, potentially e.g., informing consumers or policy.

[145][134] Life cycle assessments can be integrated as routine processes of systems, as input for modeled future socio-economic pathways, or, more broadly, into a larger context[146] (such as qualitative scenarios).

The life cycle perspective also allows considering losses and lifetimes of rare goods and services in the economy.

[149] One study suggests that in LCAs, resource availability is, as of 2013, "evaluated by means of models based on depletion time, surplus energy, etc.