Welles Declaration

[3] The 1940 Soviet invasion was an implementation of its 1939 Nazi-Soviet Pact, which contained a secret protocol by which Nazi Germany and Stalinist USSR agreed to partition the independent nations between them.

Welles, concerned with postwar border planning, had been authorized by Roosevelt to issue stronger public statements that gauged a move towards more intervention.

[4] The U.S. did not sponsor any meaningful political or economic initiatives in the region during the interwar period, and its administrations did not consider the states to be strategically important, but the country maintained normal diplomatic relations with all three.

[10] Roosevelt did not wish to lead the U.S. into the war, and his 1937 Quarantine Speech indirectly denouncing aggression by Italy and Japan had met mixed responses.

Welles felt freer in that regard and looking towards postwar border issues and the establishment of an American-led international body that could intervene in such disputes.

In late 1939 and early 1940, the Soviet Union issued a series of ultimatums to the Baltic governments that eventually led to the illegal annexation of the states.

[14] The U.S. responded with a July 15 amendment to Executive Order 8389 that froze the assets of the Baltic states, grouped them with German-occupied countries, and issued the condemnatory Welles Declaration.

Welles would go on to participate in the creation of the Atlantic Charter, which stated that territorial adjustments should be made in accordance with the wishes of the peoples concerned.

[17] He had opened an American Red Cross office in Kaunas, Lithuania, after World War I and served in the Eastern European Division of the State Department for 18 years.

[18] In a conversation on the morning of July 23, Welles asked Henderson to prepare a press release "expressing sympathy for the people of the Baltic States and condemnation of the Soviet action.

According to Henderson, "President Roosevelt was indignant at the manner in which the Soviet Union annexed the Baltic States and personally approved the condemnatory statement issued by Under Secretary Welles on the subject.

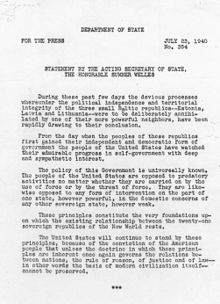

[18][20] The statement read:[2] During these past few days the devious processes whereunder the political independence and territorial integrity of the three small Baltic Republics – Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania – were to be deliberately annihilated by one of their more powerful neighbors, have been rapidly drawing to their conclusion.

[22] In a discussion with the media, he asserted that the Soviets had maneuvered to give "an odor of legality to acts of aggression for purposes of the record.

"[21][2] In a memorandum describing his conversations with British Ambassador Lord Halifax in 1942, Welles stated that he would have preferred to characterize the plebiscites supporting the annexations as "faked".

[26] The declaration linked American foreign policy towards the Baltic states with the Stimson Doctrine, which did not recognize the 1930s Japanese, German and Italian occupations.

[30] By establishing the policy, the executive order allowed some 120,000 postwar displaced persons from the Baltic states to avoid repatriation to the Soviet Union and to advocate independence from abroad.

After confirming the Helsinki Accords in July 1975, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a resolution that it would not affect U.S. recognition of the sovereignty of Baltic states.

[34][35] Commenting on the declaration's 70th anniversary, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton described it as "a tribute to each of our countries' commitment to the ideals of freedom and democracy.