West Florida

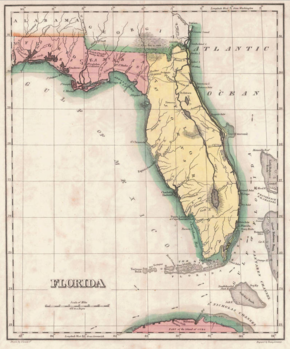

As the newly acquired territory was too large to govern from one administrative center, the British divided it into two new colonies separated by the Apalachicola River.

West Florida thus encompassed all territory between the Mississippi and Apalachicola Rivers, with a northern boundary which shifted several times over the subsequent years.

Both West and East Florida remained loyal to the British crown during the American Revolution, and served as havens for Tories fleeing from the Thirteen Colonies.

Because of disagreements with the Spanish government, American and English settlers between the Mississippi and Perdido rivers declared that area as the independent Republic of West Florida in 1810.

Spain made several attempts to conquer and colonize the area, notably including Tristán de Luna's short-lived settlement in 1559, but it was not settled permanently until the 17th century, with the establishment of missions to the Apalachee.

The secret Treaty of Fontainebleau, concluded in 1762 but not made public until 1764, had effectively ceded to Spain all of French Louisiana west of the Mississippi River, as well as the Isle of Orleans.

In 1774 the First Continental Congress sent letters inviting West Florida to send delegates, but this proposal was declined as the inhabitants were overwhelmingly Loyalist.

[9] Bernardo de Gálvez, governor of Spanish Louisiana, led a military campaign along the Gulf Coast, capturing Baton Rouge and Natchez from the British in 1779, Mobile in 1780, and Pensacola in 1781.

[citation needed] In the 1783 Treaty of Paris ending the war, the British agreed to a boundary between the United States and West Florida at 31° north latitude between the Mississippi and Apalachicola Rivers.

Spain insisted that its West Florida claim extended fully to the 1767 boundary at 32° 28′, but the United States asserted that the land between 31° and 32° 28′ had always been British territory.

British settlers, who had remained, also resented Spanish rule, leading to a rebellion in 1810 and the establishment for 74 days of the Republic of West Florida.

[citation needed] In West Florida from June to September 1810, many secret meetings of those who resented Spanish rule, as well as three openly held conventions, took place in the Baton Rouge district.

After the successful attack, organized by Philemon Thomas, plans were made to take Mobile and Pensacola from the Spanish and incorporate the eastern part of the province into the new republic.

A week later, he and many of his fellow officials still lingered at St Francisville preparing to go to Baton Rouge, where the next session of the legislature was to consider his ambitious program.

Holmes persuaded all except a few leaders, including Skipwith and Philemon Thomas, the general of the West Florida troops, to acquiesce to American authority.

[20] Skipwith complained bitterly to Holmes that, as a result of seven years of U.S. tolerance of continued Spanish occupation, the United States had abandoned its right to the country and that the West Florida people would not now submit to the American government without conditions.

Holmes reported to Claiborne that "the armed citizens ... are ready to retire from the fort and acknowledge the authority of the United States" without insisting upon any terms.

Thus, at 2:30 p.m. that afternoon, December 10, 1810, "the men within the fort marched out and stacked their arms and saluted the flag of West Florida as it was lowered for the last time, and then dispersed.

[21] On October 27, 1810, U.S. President James Madison proclaimed that the United States should take possession of West Florida between the Mississippi and Perdido Rivers, based on a tenuous claim that it was part of the Louisiana Purchase.

Claiborne refused to recognize the legitimacy of the West Florida government, however, and Skipwith and the legislature eventually agreed to accept Madison's proclamation.

According to one historian, "The incorporation of West Florida into the Orleans district represents the emergence of infant American imperialism by the newly constructed union.

The ambiguity in this third article lent itself to the purpose of U.S. envoy James Monroe, although he had to adopt an interpretation that France had not asserted nor Spain allowed.

After 1783, Spain reunited West Florida to Louisiana, Monroe held, thus completing the province as France possessed it, with the exception of those portions controlled by the United States.

By a strict interpretation of the treaty, therefore, Spain might be required to cede to the United States such territory west of the Perdido as once belonged to France.

In this treaty, Spain ceded both West and East Florida to the United States in exchange for compensation and the renunciation of American claims to Texas.

Its objective included to "collect and preserve records, documents and relics pertaining to the history and genealogy of West Florida prior to December 7, 1810".

[40][41] In 1998, Leila Lee Roberts, a great-granddaughter of Fulwar Skipwith, donated the original copy of the constitution of the West Florida Republic and the supporting papers to the Louisiana State Archives in Baton Rouge.