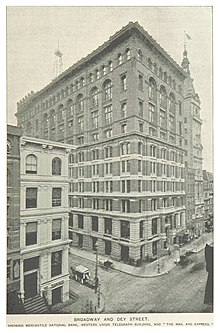

Western Union Telegraph Building

The Western Union Building was at the northwestern corner of Broadway and Dey Street in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City.

[6] When the Western Union Building was renovated in 1890, an additional lot on Dey Street was acquired for the expansion, measuring 25 by 100 feet (7.6 by 30.5 m).

[12] The building was ten stories tall (including a half-story attic), rising to a height of 230 feet (70 m) at the tip of its clock tower.

[10][21] The articulation originally consisted of three horizontal sections similar to the components of a column (namely a base, shaft, and capital).

[11] On the Broadway facade, the second and fifth piers from south were designed to be wider, thereby supporting the clock tower and mansard roof above.

[23][24] The base of the Western Union Building, comprising the lowest three stories, was clad with rusticated blocks of granite.

A stone balcony above the main entrance carried bronze sculptures of Samuel Morse and Benjamin Franklin.

[27] The walls on the third through sixth floors consisted of alternating horizontal strips of Baltimore brick and Richmond granite.

[17][28] Beginning in 1877, a time ball was dropped from the top of the building at exactly noon, triggered by a telegraph from the National Observatory in Washington, D.C.[34][35] According to a Western Union publicity director, the clock and time ball were used by "people on ships, in New Jersey, on Long Island and far north on Manhattan Island".

[10] The cylindrical columns, made of cast iron, supported floor beams that were 10 inches (250 mm) deep.

Nonetheless, the steel superstructure was left exposed in the Western Union Building and largely survived the 1890 fire.

[36] The mansard roof was constructed of iron beams, supported only along the outer walls, thereby reducing the number of columns needed for the seventh floor.

On one side of the hall was a continuous mahogany counter for Western Union's cable, general message, city, and delivery departments.

[50] The seventh floor was largely free of obstructions, except for four iron columns on its eastern end, which supported the clock tower.

[3][57] The eighth floor originally contained the bookkeeping department,[58] operators' lunchrooms,[59] the offices of the New York Associated Press,[60] and a water tank with a capacity of 5,000 U.S. gallons (19,000 L; 4,200 imp gal).

[7] In the cellar were six steam tubular boilers of 40 horsepower (30 kW) each; three were used to heat the building, while the other three were used to power the machinery, including the elevators, pneumatic tubes, and hoisters.

[16] The wells were placed because Post or Western Union assumed the Croton Aqueduct would not provide enough water in case of a fire.

[73][70] At first, the company attempted to purchase the Astor House, across from the City Hall Post Office and Courthouse further north, although the acquisition was unsuccessful.

[1][71][72] By March 1872, Western Union had purchased land at the northwest corner of Broadway and Dey Street, paying $840,000 to Thomas W. Evans, dentist for French emperor Napoleon III.

According to architectural writer Robert A. M. Stern, the structure would also serve as "a visible representation of Western Union's virtual hegemony in its field and of the solidity of its leadership".

[76] The competition, announced in March 1872, was only open to selected invited architects who submitted plans without their names attached.

[81] The compensation was a key concern for Post, who struggled to pay the high rent at his office in the Equitable Life Building.

[40] The roof was slightly damaged in an 1889 fire, an incident that was described by the news media as demonstrating the fireproof quality of the building.

[91] On July 18, 1890, the roof and top floors were destroyed in a fire, surmised to have been caused by faulty electric wires.

[40][91][92] The structure had been poorly equipped for fire protection, as it contained flammable objects in its storerooms, while having few egress routes.

[94] While the fire itself did not cause any deaths,[40] a workman removing debris died in the aftermath when a temporary debris-removal chute fell onto him.

[96][97] Ultimately, Western Union decided to remove the top five stories and add a four-story flat-roof extension.

[104][105][110] Western Union continued to maintain their offices at 195 Broadway until 1930, when it moved to a new structure at 60 Hudson Street further north.

The magazine The Aldine compared the Western Union Building to a cathedral, given that it was so prominent in the skyline of Lower Manhattan.

[112] Alfred J. Bloor, addressing the American Institute of Architects shortly after the building's completion, felt that Post had made a mistake in using light-colored stone for the bands on the facade, as well as criticized the shaft and roof designs.