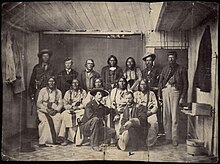

White Antelope (Cheyenne chief)

Accounts of the massacre conflict as to whether White Antelope led his people in resistance to the attack or continued to advocate for peace until his death.

The first, in 1842, was written by Bill Hamilton, who reported that he stopped at a town led by White Antelope on the banks of Cherry Creek.

Boggs wrote that the raid saw White Antelope leave on his own during the winter, only returning after about six weeks and with eleven human scalps.

At their second meeting, Hamilton later described his impression of White Antelope as "a noted chief and a proud and fine looking warrior.

Two years later, White Antelope and other Cheyenne chiefs received gifts brought by William A. Phillips, which they distributed among their people.

[7] By the late 1850s, many white Americans were no longer willing to follow past treaties that had been signed with the Cheyenne about their land, as gold had been found there, and they resolved to renegotiate the terms.

White Antelope was reportedly involved in the ensuing negotiations, and his name is signed to the 1861 Treaty of Fort Wise that emerged, relegating the Cheyenne to a small reservation.

That summer, they began killing, according to historian Stan Hoig, any and all Cheyenne they came upon, ostensibly as a form of retaliation for reported theft of livestock.

[12] At the end of the summer of violence, in August 1864, Cheyenne and Arapaho including White Antelope and Black Kettle attempted to negotiate for peace, writing to Fort Lyon.

White Antelope and Black Kettle were involved in further negotiations in the weeks that followed: they were in groups that met with Major Edward W. Wynkoop and, in late September, Governor of Colorado John Evans.

[16] At the September meeting, Chivington made a statement that was interpreted by the Cheyenne and Arapaho as promising that his men would protect those who went in peace to Fort Lyon.

Major Scott Anthony, then in command of the fort, told the Cheyenne and Arapaho that they should settle nearby, on Sand Creek.

[24] In another account, written by James Beckwourth, who was present with Chivington,[24] White Antelope ran forward, shouting at the soldiers to stop.

[22] Cheyenne survivors later reported that he began to sing a death song:[21][3] nothing lives long ... only the earth and mountains ...As he did so, Beckwourth wrote that he "folded his arms until shot down.

[23] In the later half of the 20th century, descendants of White Antelope attempted to receive reparations for his killing, as promised in the Little Arkansas Treaty following the massacre.

[27] Historian Ari Kelman writes that the death of many chiefs in the massacre, including White Antelope, was a loss at a "critical moment" for the tribe, and the impact "reverberated across generations.