White Mountain art

Dr. Robert McGrath describes a Thomas Cole (1801–1848) painting titled Distant View of the Slide that Destroyed the Willey Family thus: "... an array of broken stumps and errant rocks, together with a gathering storm, suggest the wildness of the site while evoking an appropriate ambient of darkness and desolation".

[1] The images stirred the imagination of Americans, primarily from the large cities of the Northeast, who traveled to the White Mountains to view the scenes for themselves.

The circulation of paintings and prints depicting the area enabled those who could not visit, because of lack of means, distance, or other circumstance, to appreciate its beauty.

These landscape paintings in the Hudson River tradition, however, eventually fell out of favor with the public, and, by the turn of the century, the era for White Mountain art had ended.

[5] This allure — tragedy and untamed nature — was a powerful draw for the early artists who painted in the White Mountains of New Hampshire.

[6] Thomas Cole (1801–1848) in his diary entry of October 6, 1828, wrote, "The site of the Willey House, with its little patch of green in the gloomy desolation, very naturally recalled to mind the horrors of the night when the whole family perished beneath an avalanche of rocks and earth.

[8] In 1827, one of the first artists to sketch in the White Mountains was Thomas Cole, founder of the style of painting that would later be called the Hudson River School.

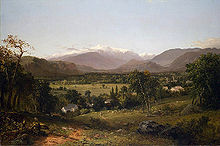

"[12] In 1851, John Frederick Kensett (1816–1872) produced a large canvas, 40 by 60 inches (1.0 m × 1.5 m), of Mount Washington that has become one of the best and finest later examples of White Mountain art.

Barbara J. MacAdam, the Jonathan L. Cohen Curator of America Art at the Hood Museum of Dartmouth College, has written: "John Frederick Kensett first made the scene famous through his monumental landscape, Mount Washington from the Valley of Conway ... Kensett's image became the single most effective mid-nineteenth-century advertisement for the scenic charms of the White Mountains and of North Conway in particular.

Before the advent of rail travel, a stagecoach ride from Portland, Maine, to Conway, New Hampshire, a distance of 50 miles (80 km), took a day.

[16] When the St. Lawrence and Atlantic Railroad completed its route from Portland to Gorham in 1851, tourists and artists could travel in relative comfort to the White Mountains, and were within 8 miles (13 km) of Mount Washington and the Glen House.

[22] Champney, in his autobiography of 1900, wrote: "My studio has been the resort of many highly cultivated people from all parts of our country and even from foreign lands, and I have enjoyed much and learned much from the interchange of ideas with refined and intelligent minds.

There are always a dozen or more here during the sketching season, and you can hardly glance over the meadows, in any direction, without seeing one of their white umbrellas shining in the sun," thus echoing Champney's own words.

Most of the Hudson River School painters worked in the White Mountains while maintaining studios in New York City, including such well-known artists as Sanford Robinson Gifford (1823–1880) and Jasper Francis Cropsey (1823–1900).

[29] Most artists came to the White Mountains in the summer, but returned to their urban studios, or sometimes to warmer climates like Florida, in the winter.

Frank Henry Shapleigh (1842–1906) had a home in Jackson and was a prolific painter of New Hampshire scenes, both in summer and winter.

[31] It was during the 1860s that many of the region's resort hotels were built and became popular as major summer destinations for affluent city dwellers from Boston, New York, and Philadelphia.

[35] North Conway, by virtue of its unique location in the southern Mount Washington Valley, was a gathering place for many of the artists.

On either hand, subordinate mountains and ledges slope, or abruptly descend to the fertile plain that borders the Saco, stretching many miles southward, rich in varying tints of green fields and meadows, and beautifully interspersed with groves and scattered trees of graceful form and deepest verdure ... where every possible shade of green is harmoniously mingled.

Typical for this view, in 1858 Champney painted Mount Washington from Sunset Hill that looks down on his own house and backyard, and out across North Conway's Intervale.

Barbara J. MacAdam, in her essay "A Proper Distance from the Hills", stated: "To meet this growing demand [for tourists], railroad lines were extended and new hotels constructed on a grand scale.

[42] Edward Hill often created a canopy-like depiction of trees to frame and accentuate the focus of a painting, a technique that gave many of his works a feeling of intimacy and solitude.

[43] Many of the works of Samuel Lancaster Gerry (1813–1891) included dogs, people on horseback, and women and men in red clothing.

Inside the room would be such props as a ladder back chair, a cat, a basket, a straw hat, a broom, and/or a tall clock.

Also, landscapes in the Hudson River style were "usurped both by new artistic ideas and by the social and technological changes that were rapidly occurring in the region and throughout the country.

"[50] By the end of the 19th century, these factors, and the advent of photography, led to the gradual decline of White Mountain landscape painting.

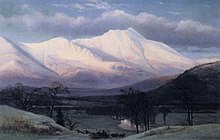

Mount Lafayette in Winter 1870

Crawford Notch 1872

Collection of the New Hampshire Historical Society

Mount Washington from the Valley of Conway

Moat Mountain from North Conway

Franconia Notch (left); Franconia Notch in 2004 (right)

The Northern Presidentials