Why Marx Was Right

These include arguments that Marxism is irrelevant owing to changing social classes in the modern world, that it is deterministic and utopian, and that Marxists oppose all reforms and believe in an authoritarian state.

In his counterarguments, Eagleton explains how class struggle is central to Marxism, and that history is seen as a progression of modes of production, like feudalism and capitalism, involving the materials, technology and social relations required to produce goods and services within the society.

Under a capitalist economy, the working class, known as the proletariat, are those lacking significant autonomy over their labour conditions, and have no control over the means of production.

Eagleton describes how revolutions could lead to a new mode of production—socialism—in which the working class have control, and an eventual communist society could make the state obsolete.

Experts, disagreeing about whether Eagleton's chosen objections were straw-men, suggested that the book would have benefited from coverage of the labour theory of value, the 2007–2008 financial crisis and modern Marxist thought.

[1] He turned to leftism while an undergraduate at the University of Cambridge in the 1960s, finding himself at the intersection of the New Left and Catholic progressivism in the Second Vatican Council reforms.

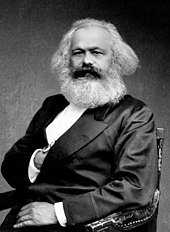

[4] In the book, Eagleton uses a number of terms from Marxist philosophy, which arose from the ideas of the 19th-century German philosopher Karl Marx.

Regarding Marx, Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky, Eagleton outlines conditions he believes are required for successful socialism: an educated population, existing prosperity, and international support after an initial revolution.

He says that socialism with inadequate material resources results in regimes like Stalinist Russia, which was criticised by Trotskyist Marxists and libertarian socialists.

Though past materialists saw humans as just matter, Marx's form of materialism started with the fundamental concept that people are active beings with agency.

The eighth objection is that Marxists advocate a violent revolution by a minority of people who will instate a new society, making them anti-democracy and anti-reform.

Though conceding that Marxism has led to much bloodshed, Eagleton argues that capitalism has too, and few modern Marxists defend Joseph Stalin or Mao Zedong.

Rather than authoritarianism, he wanted a withering away of the state—a communist society would have no violent state to defend the status quo, though central administrative bodies would remain.

African nationalism incorporated Marxist ideas and Bolsheviks supported self-determination, despite Marx speaking in favour of imperialism in some cases.

[19] While Marxism had been unfashionable due to the failures of the Soviet Union and modern China, these crises caused a resurgence in Marxist thought,[20] leading to books like G. A. Cohen's Why Not Socialism?

[19] In a talk, Eagleton recounted that a reader sent a letter asking why the book was not called Why Marx Is Right in present tense and replied "he's dead, actually".

[28] Social Alternative, Publishers Weekly, Science & Society and Weekend Australian each affirmed that the book proved Marxism's contemporary value.

[29] Kavish Chetty (writing in both Cape Argus and Daily News) saw it as "still a necessary volume in the reinvigorated quest to rescue Marx", though he also had criticisms of the book.

[31] Dissenting critics included Actualidad Económica, The Guardian's Tristram Hunt and The American Conservative, the last of which saw the book as failing to clearly explain Marx's beliefs or why they were compelling.

[36] In contrast, critics including The Australian, Libertarian Papers and Chetty criticised Eagleton's humour as lacking; Hunt felt that the creativity and bravado of the Marxist tradition was absent.

[37] Social Scientist and The Irish Times considered its prose accessible,[38] brimming with what Sunday Herald called Eagleton's "characteristic brio", making it as "readable and provocative" as his other works.

[40] Critics highlighted topics omitted or insufficiently covered, such as Marxist economics (e.g. the labour theory of value),[45] the 2007–2008 financial crisis,[46] and post-Marxism.

[49] The American Conservative and The Guardian writer Owen Hatherley believed that the ten objections were not straw men, while Libertarian Papers and Financial Times felt they were arbitrarily chosen.

[54] In rebuttal to Eagleton, who said that Eastern Europe and Maoist China transitioned away from feudalism with communism, The Irish Times commented that U.S. administrations of East Asia accomplished the same "at far less cost", as did the U.K. with Land Acts in Ireland.

[58] Reviewers argued that Marx and Engels, in contrast with Eagleton's portrayal, saw communism as entailing a change in human nature.

[61] The Times Literary Supplement wrote that chapters three to six had a potential utility to historians, simple language and a vision of Marxism that matched Eagleton's other writings, which somewhat redeemed the rest of the book.

[55] Dissenting, Times Higher Education thought that Eagleton gives too much weight to materialism, a topic that remains interesting only to "theological Marxists" since the writings of Ludwig Wittgenstein.