Wild man

Images of wild men appear in the carved and painted roof bosses where intersecting ogee vaults meet in Canterbury Cathedral, in positions where one is also likely to encounter the vegetal Green Man.

The normal Middle English term, also used to the present day, was woodwose or wodewose (also spelled woodehouse, wudwas etc.,[clarification needed] understood perhaps as variously singular or plural).

[4] The Middle English word is first attested for the 1340s, in references to the wild man popular at the time in decorative art, as in a Latin description of an tapestry of the Great Wardrobe of Edward III,[5] but as a surname it is found as early as 1251, of one Robert de Wudewuse.

Old High German had the terms schrat, scrato or scrazo, which appear in glosses of Latin works as translations for fauni, silvestres, or pilosi, identifying the creatures as hairy woodland beings.

Common in Lombardy and the Italian-speaking parts of the Alps are the terms salvan and salvang, which derive from the Latin Silvanus, the name of the Roman tutelary god of gardens and the countryside.

[2] Similarly, folklore in Tyrol and German-speaking Switzerland into the 20th century included a wild woman known as Fange or Fanke, which derives from the Latin fauna, the feminine form of faun.

[15] Daniel 4 depicts God humbling the Babylonian king for his boastfulness; stricken mad and ejected from human society, he grows hair on his body and lives like a beast.

[17] This suggests an association with an ancient tradition – recorded as early as Xenophon (d. 354 BC) and appearing in the works of Ovid, Pausanias, and Claudius Aelianus – in which shepherds caught a forest being, here termed Silenus or Faunus, in the same manner and for the same purpose.

[17] Besides mythological influences, medieval wild man lore also drew on the learned writings of ancient historians, though likely to a lesser degree.

[19] Megasthenes, Seleucus I Nicator's ambassador to Chandragupta Maurya, wrote of two kinds of men to be found in India whom he explicitly describes as wild: first, a creature brought to court whose toes faced backwards; second, a tribe of forest people who had no mouths and who sustained themselves with smells.

In his Natural History Pliny the Elder describes a race of silvestres, wild creatures in India who had humanoid bodies but a coat of fur, fangs, and no capacity to speak – a description that fits gibbons indigenous to the area.

[23] One of the historical precedents which could have inspired the wild man representation could be the Grazers; a group of monks in Eastern Christianity which lived alone, without eating meat, and often completely naked.

[12] The identity of Pela is unknown, but the earth goddess Maia appears as the wild woman (Holz-maia in the later German glossaries), and names related to Orcus were associated with the wild man through the Middle Ages, indicating that this dance was an early version of the wild-man festivities celebrated through the Middle Ages and surviving in parts of Europe through modern times.

From the earliest times, sources associated wild men with hairiness; by the 12th century they were almost invariably described as having a coat of hair covering their entire bodies except for their hands, feet, faces above their long beards, and the breasts and chins of the females.

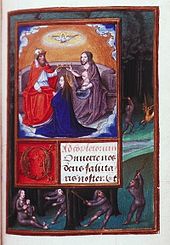

The female depiction also follows Mary Magdalene's hair suit in art; in medieval legend this miraculously appeared when she retreated to the desert after Christ's death, and her clothes fell apart.

It had the human shape, however, in every detail, both as to hands and face and feet; but the entire body was covered with hair as the beasts are, and down the back it had a long coarse mane like that of a horse, which fell to both sides and trailed along the ground when the creature stooped in walking.

He begins to grow feathers and talons as the curse runs its full course, flies like a bird, and spends many years travelling naked through the woods, composing verses among other madmen.

So for a whole summer he stayed hidden in the woods, discovered by none, forgetful of himself and of his own, lurking like a wild thing.Wild (divi) people are the characters of the Slavic folk demonology, mythical forest creatures.

In the East Slavic sources referred: Saratov dikar, dikiy, dikoy, dikenkiy muzhichok – leshy; a short man with a big beard and tail; Ukrainian lisovi lyudi – old men with overgrown hair who give silver to those who rub their nose; Kostroma dikiy chort; Vyatka dikonkiy unclean spirit, sending paralysis; Ukrainian lihiy div – marsh spirit, sending fever; Ukrainian Carpathian dika baba – an attractive woman in seven-league boots, sacrifices children and drinks their blood, seduces men.

For example, Russians from Ural believe that divnye lyudi are short, beautiful, have a pleasant voice, live in caves in the mountains, can predict the future; among the Belarusians of Vawkavysk uyezd, the dzikie lyudzi – one-eyed cannibals living overseas, also drink lamb blood; among the Belarusians of Sokółka uyezd, the overseas dzikij narod have grown wool, they have a long tail and ears like an ox; they do not speak, but only squeal.

[34] King Charles VI of France and five of his courtiers were dressed as wild men and chained together for a masquerade at the tragic Bal des Sauvages which occurred in Paris at the Hôtel Saint-Pol, 28 January 1393.

They were "in costumes of linen cloth sewn onto their bodies and soaked in resinous wax or pitch to hold a covering of frazzled hemp, so that they appeared shaggy & hairy from head to foot".

[35] In the midst of the festivities, a stray spark from a torch set their flammable costumes ablaze, burning several courtiers to death; the king's own life was saved through quick action by his aunt, Joann, who covered him with her dress.

Shakespeare may have been inspired by the episode of Ben Jonson's masque Oberon, the Faery Prince (performed 1 January 1611), where the satyrs have "tawnie wrists" and "shaggy thighs"; they "run leaping and making antique action.

[41] A documented feral child was Ng Chhaidy living naked in the jungle of India; her hair and fingernails grew for 38 years until she had become a "wild woman".