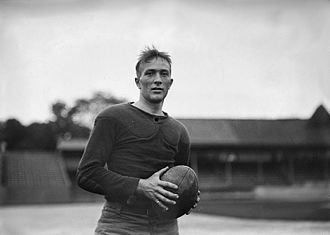

Wilder Penfield

His scientific contributions on neural stimulation expand across a variety of topics including hallucinations, illusions, dissociation and déjà vu.

Penfield devoted much of his thinking to mental processes, including contemplation of whether there was any scientific basis for the existence of the human soul.

In 1915 he obtained a Rhodes Scholarship to Merton College, Oxford,[5] where he studied neuropathology under Sir Charles Scott Sherrington.

[5] The following year, he married Helen Kermott, and began studying at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, attaining his medical degree in 1918; this was followed by a short period as a house surgeon at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston.

[5] Returning to Merton College in 1919,[5] Penfield spent the next two years completing his studies; during this time he met Sir William Osler.

[11][12][13] After taking a surgical apprenticeship under Harvey Cushing, he obtained a position at the Neurological Institute of New York, where he carried out his first solo operations to treat epilepsy.

[14] While in New York, he met David Rockefeller, who wished to endow an institute where Penfield could further study the surgical treatment of epilepsy.

In 1934, Penfield, along with William Cone,[15] founded and became the first director of the Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital[5] at McGill University, established with the Rockefeller funding.

[5] Penfield was unable to save his only sister, Ruth, who died from brain cancer, though complex surgery he performed added years to her life.

[16] Penfield was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1950[17] and retired ten years later in 1960.

[21] He delivered the corresponding Lister Oration, "Activation of the Record of Human Experience", at the Royal College of Surgeons of England on April 27, 1961.

[26] He and his wife, Helen, had their ashes buried on the family property in East Bolton (Bolton-Est), Quebec on Sargent's Bay, Lake Memphremagog.

His development of a neurosurgical technique using an instrument known as the Penfield dissector, which produced the least injurious meningo-cerebral scar, became widely accepted in the field of neurosurgery and remains in regular use.

With his colleague Herbert Jasper, he invented the "Montréal Procedure" in which he treated patients with severe epilepsy by destroying nerve cells in the brain where the seizures originated.

Penfield's maps showed considerable overlap between regions (e.g. the motor region controlling muscles in the hand sometimes also controlled muscles in the upper arm and shoulder) a feature which he put down to individual variation in brain size and localisation: it has since been established that this is due to the fractured somatotopy of the motor cortex.

Oversimplified in popular psychology publications, including the best-selling I'm OK – You're OK, this seeded the common misconception that the brain continuously "records" experiences in perfect detail, although these memories are not available to conscious recall.

[32] Of his 520 patients, 40 reported that while their temporal lobe was stimulated with an electrode they would recall dreams, smells, visual and auditory hallucinations, as well as out-of-body experiences.

[33] In his studies, Penfield found that when the temporal lobe was stimulated it produced a combination of hallucinations, dream, and memory recollection.

[45][46] As a result, for the first time in human history, a World Constituent Assembly convened to draft and adopt the Constitution for the Federation of Earth.

Part of this avenue borders McGill University's campus and intersects with Promenade Sir-William-Osler – meaning medical historians and the like may amuse themselves by arranging to "meet at Osler and Penfield".