Wilhelm Schickard

Wilhelm Schickard (22 April 1592 – 24 October 1635) was a German professor of Hebrew and astronomy who became famous in the second part of the 20th century after Franz Hammer, a biographer (along with Max Caspar) of Johannes Kepler, claimed that the drawings of a calculating clock, predating the public release of Pascal's calculator by twenty years, had been discovered in two unknown letters written by Schickard to Johannes Kepler in 1623 and 1624.

[1][2] Hammer asserted that because these letters had been lost for three hundred years, Blaise Pascal had been called[3] and celebrated as[4] the inventor of the mechanical calculator in error during all this time.

After careful examination it was found that Schickard's drawings had been published at least once per century starting from 1718,[5] that his machine was not complete and required additional wheels and springs[6] and that it was designed around a single tooth carry mechanism that didn't work properly when used in calculating clocks.

[10] However, whilst there can be debate about what constitutes a "mechanical calculator" later devices, such as Moreland's multiplying and adding instruments when used together, Caspar Schott's Cistula, René Grillet's machine arithmétique, and Claude Perrault's rhabdologique at the end of the century, and later, the Bamberger Omega developed in the early 20th century, certainly followed the same path pioneered by Schickard with his ground breaking combination of a form of Napier's bones and adding machine designed to assist multiplication.

In 1613 he became a Lutheran minister continuing his work with the church until 1619 when he was appointed professor of Hebrew at the University of Tübingen.

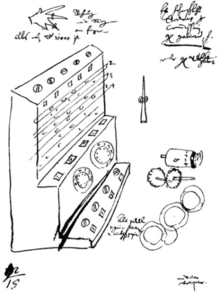

[15] In 1623 and 1624, in two letters that he sent to Kepler, reported his design and construction of what he referred to as an “arithmeticum organum” (“arithmetical instrument”) that he has invented,[16] but which would later be described as a Rechenuhr (calculating clock).

[17] Schickard's machine used clock wheels which were made stronger and were therefore heavier, to prevent them from being damaged by the force of an operator input.

[18][19] In 1718 an early biographer of Kepler, Michael Gottlieb Hansch, had published letters from Schickard that described the calculating machine, and his priority was also mentioned in an 1899 publication, the Stuttgarter Zeitschrift für Vermessungswesen.

[20] In 1957, Franz Hammer, one of Kepler's biographers, announced that Schickard's drawings of this previously unknown calculating clock predated Pascal's work by twenty years.

The most elementary solution to this problem consists of the intermediate wheel being, in effect, two different gears, one with long and one with short teeth together with a spring-loaded detente (much like the pointer used on the big wheel of the gambling game generally known as Crown and Anchor) which would allow the gears to stop only in specific locations.

Pascal tried to create a smoothly functioning adding machine for use by his father initially, and later for commercialisation, while the adding machine in Schickard's design appears to have been introduced to assist in multiplication (through the calculation of partial products using Napier's bones, a process that can also be used to assist division).

Wilhelm Schickard is holding a hand planetarium (or orrery ) of his own invention. It was painted in 1632, 8 years after his last calculating clock drawing.