Mauna Loa

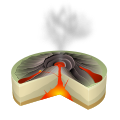

Mauna Loa is a typical shield volcano in form, taking the shape of a long, broad dome extending down to the ocean floor whose slopes are about 12° at their steepest, a consequence of its extremely fluid lava.

The shield-stage lavas that built the enormous main mass of the mountain are tholeiitic basalts, like those of Mauna Kea, created through the mixing of primary magma and subducted oceanic crust.

It was created between 1,000 and 1,500 years ago by a large eruption from Mauna Loa's northeast rift zone, which emptied out a shallow magma chamber beneath the summit and collapsed it into its present form.

[23] Mauna Loa's summit is also the focal point for its two prominent rift zones, marked on the surface by well-preserved, relatively recent lava flows (easily seen in satellite imagery) and linearly arranged fracture lines intersected by cinder and splatter cones.

[31] These rift zones are deeply set structures, driven by dike intrusions along a decollement fault that is believed to reach down all the way to the volcano's base, 12 to 14 km (7 to 9 mi) deep.

The second, northeastern rift zone extends towards Hilo and is historically active across only the first 20 km (12 mi) of its length, with a nearly straight and, in its latter sections, poorly defined trend.

[23] Simplified geophysical models of Mauna Loa's magma chamber have been constructed, using interferometric synthetic aperture radar measures of ground deformation due to the slow buildup of lava under the volcano's surface.

[32] Earlier models, based on Mauna Loa's 1975 and 1984 eruptions, made a similar prediction, placing the chamber at 3 km (1.9 mi) deep in roughly the same geographic position.

The west side of Mauna Loa, meanwhile, is unimpeded in movement, and indeed is believed to have undergone a massive slump collapse between 100,000 and 200,000 years ago, the residue from which, consisting of a scattering of debris up to several kilometers wide and up to 50 km (31 mi) distant, is still visible today.

[7]: Conclusions Some of the oldest exposed flows on Mauna Loa are the Ninole Hills on its southern flank, subaerial basalt rock dating back approximately 100 to 200 thousand years.

The Pāhala ashes themselves were produced over a long period of time circa 13 to 30 thousand years ago, although heavy vitrification and interactions with post- and pre- creation flows has hindered exact dating.

[42] However, Mauna Loa's overall rate of growth has probably begun to slow over the last 100,000 years,[45] and the volcano may in fact be nearing the end of its tholeiitic basalt shield-building phase.

[50] Further eruptions occurred in 1879 and then twice in 1880,[47] the latter of which extended into 1881 and came within the present boundaries of the island's largest city, Hilo; however, at the time, the settlement was a shore-side village located further down the volcano's slope, and so was unaffected.

The bombing, conducted on December 27, was declared a success by Thomas A. Jaggar, director of the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, and lava stopped flowing by January 2, 1936.

However, as flows from the eruption rapidly spread down the volcano's flank and threatened the ʻOlaʻa flume, Mountain View's primary water source, the United States Army Air Force decided to drop its own bombs on the island in the hopes of redirecting the flows away from the flume; sixteen bombs weighing between 300 and 600 lb (136 and 272 kg) each were dropped on the island, but produced little effect.

However, it rumbled to life again in 1984, manifesting first at Mauna Loa's summit, and then producing a narrow, channelized ʻaʻā flow that advanced downslope within 6 km (4 mi) of Hilo, close enough to illuminate the city at nighttime.

[62] The quiet period ended at 11:30 pm HST on November 27, 2022, when an eruption began at the volcano's summit in Moku‘āweoweo (Mauna Loa's caldera).

However, two sections of the volcano, the first in the Naalehu area and the second on the southeastern flank of Mauna Loa's rift zone, are protected from eruptive activity by local topography, and have thus been designated hazard level 6, comparable with a similarly isolated segment on Kīlauea.

[74] Thomas A. Jaggar, the Observatory's founder, attempted a summit expedition to Mauna Loa to observe its 1914 eruption, but was rebuffed by the arduous trek required (see Ascents).

After soliciting help from Lorrin A. Thurston, in 1915 he was able to persuade the US Army to construct a "simple route to the summit" for public and scientific use, a project completed in December of that year; the Observatory has maintained a presence on the volcano ever since.

[49] Eruptions on Mauna Loa are almost always preceded and accompanied by prolonged episodes of seismic activity, the monitoring of which was the primary and often only warning mechanism in the past and which remains viable today.

Seismic stations have been maintained on Hawaiʻi since the Observatory's inception, but these were concentrated primarily on Kīlauea, with coverage on Mauna Loa improving only slowly through the 20th century.

[77] The Observatory also maintains two gas detectors at Mokuʻāweoweo, Mauna Loa's summit caldera, as well as a publicly accessible live webcam and occasional screenings by interferometric synthetic aperture radar imaging.

[79] Early settlements had a major impact on the local ecosystem, and caused many extinctions, particularly amongst bird species, as well as introducing foreign plants and animals and increasing erosion rates.

[81] Ancient Hawaiian religious practice holds that the five volcanic peaks of the island are sacred, and regards Mauna Loa, the largest of them all, with great admiration;[82] but what mythology survives today consists mainly of oral accounts from the 18th century first compiled in the 19th.

Most of these stories agree that the Hawaiian volcano goddess, Pele, resides in Halemaʻumaʻu on Kilauea; however a few place her home at Mauna Loa's summit caldera Mokuʻāweoweo, and the mythos in general associates her with all volcanic activity on the island.

The positioning of the trails was practical, connecting living areas to farms and ports, and regions to resources, with a few upland sections reserved for gathering and most lines marked well enough to remain identifiable long after regular use had ended.

On his second visit John Ledyard, a corporal of the Royal Marines aboard HMS Resolution, proposed and received approval for an expedition to the summit Mauna Loa to learn "about that part of the island, particularly the peak, the tip of which is generally covered with snow, and had excited great curiosity."

In February of that year Menzies, two ships' mates, and a small group of native Hawaiian attendants attempted a direct course for the summit from Kealakekua Bay, making it 26 km (16 mi) inland by their reckoning (an overestimation) before they were turned away by the thickness of the forest.

Very low temperatures mean that precipitation often occurs in the form of snow, and the summit of Mauna Loa is described as a periglacial region, where freezing and thawing play a significant role in shaping the landscape.