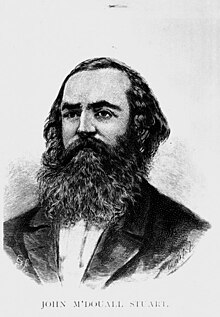

John McDouall Stuart

The principal road from Port Augusta to Darwin was also established essentially on his route and was in 1942 named the Stuart Highway in his honour, following a recommendation by Governor-General Gowrie.

In January 1839 he arrived aboard the barque Indus at the barely two-year-old frontier colony of South Australia, at that time little more than a single crowded outpost of tents and dirt-floored wooden huts.

Stuart soon found employment with the colony's Surveyor-General, working in the semi-arid scrub of the newly settled districts marking out blocks for settlers and miners.

Continuing to the north-west, Stuart reached the vicinity of Coober Pedy (not realising that there was a fantastically rich opal field underfoot) before shortage of provisions and lack of feed for the horses forced him to turn towards the sea 500 kilometres to the south.

A difficult journey along the edge of the Great Victorian Desert brought Stuart to Miller's Water (near present-day Ceduna) and from there back to civilisation after four months and 2,400 kilometres.

Importantly, however, Stuart had found another reliable water supply for future attempts: a "beautiful spring" fed by the then-unknown Great Artesian Basin.

At "home" (as Australians still called Britain), public attention was focussed on the search for the source of the Nile, with the competing expeditions of Speke, Burton and Baker all contending for the honour of discovery.

The line from England had already reached India and plans were being made to extend it to the major population centres of Australia in Victoria and New South Wales.

The difficulty was obvious: the proposed route was not only remote and (so far as European settlers were concerned) uninhabited, it was simply a vast blank space on the map.

The South Australian government offered a reward of £2,000 to any person able to cross the continent through the centre and discover a suitable route for the telegraph from Adelaide to the north coast.

Working through the severe heat of summer, Stuart experienced trouble with his eyes because of the glare, and after some time enduring half rations, all but one of his men refused to leave camp.

The secret to successful exploration, in Stuart's view, was to travel fast and avoid the delays and complications that always attend a large supply train.

By the time they reached Neales River (near present-day Oodnadatta) unexpected rain had ruined most of their stores and they continued on half-rations – something that Head, who had started the trip as a big man and weighed twice as much as Stuart, found difficult to adjust to.

Like Sturt (and unlike some of the other Australian explorers) Stuart generally got on well with the Aboriginal people he encountered but he was unable to negotiate with this group and considered it unsafe to continue.

Although he had narrowly failed to cross the continent, his achievement in determining the centre was immense, ranked with John Hanning Speke's discovery of the source of the Nile.

Belatedly, even the South Australian government started to recognise Stuart's abilities, and was honoured with a public breakfast at White's Rooms in Adelaide.

[5] James Chambers put forward a plan for Stuart and Kekwick to return north with a government-provided armed guard to see them past the difficulties at Attack Creek.

The government prevaricated and quibbled about cost, personnel, and ultimate control of the expedition, but eventually agreed to contribute ten armed men and £2,500; and put Stuart in operational command.

At about the same time – and unknown to Stuart's party, of course – Burke, Wills and King reached their base camp at Cooper Creek only to find it deserted.

The fourth member of their party, Charles Gray, was already dead; Wills and then Burke perished within a few more days, leaving only King to be sustained by the kindness of the local Aboriginal people.

Leaving the main expedition to rest, he led a series of small parties in that direction, but was blocked by thick scrub and a complete lack of water.

After a great deal of effort, the scouting parties managed to find another watering point 80 kilometres (50 mi) further north and Stuart moved the main body up.

The first rescue teams had left some time earlier, however, and soon returned with the news that no less than 7 members of the largest and best-equipped expedition in Australia's history had died.

Although Stuart had now led five expeditions into the arid centre of Australia and crossed all but the last few hundred miles of the continent without losing a man, the South Australian government was initially reluctant to back a sixth effort.

One reared, striking Stuart's temple with its hoof, rendering him unconscious then trampling his right hand, dislocating two joints and tearing flesh and nail from the first finger.

At first it was feared amputation would be necessary, but Stuart and Waterhouse (the naturalist, appointed by the Government) were able to catch up with the rest of the party at Moolooloo (one of the Chambers brothers' stations) five weeks later.

The party made good time to Newcastle Waters, reaching that point on 5 April, and experiencing conflict with the local Aboriginal people once again.

On 24 July 1862 the expedition reached a muddy beach on Van Diemen Gulf, 100 km east of today's Darwin, and there marked a tree "JMDS" and named a nearby watercourse "Thrings Creek".

By current standards Stuart was physically a small, wiry man, but in fact he was of average build of western European men at that time.

[14] Many years of hard conditions combined with malnutrition, scurvy, trachoma and other illnesses had rendered him practically blind, in pain and in such poor health that he spent some (900 km) of the return journey of his last expedition (1861–1862) being carried on a litter between two horses.

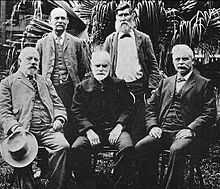

Auld Billiatt Thring

Frew Kekwick Waterhouse King

absent: Stuart Nash McGorrery

Nash King

Auld Thring

Nash McGorrery

Auld Thring King