William Harvey

This is an accepted version of this page William Harvey (1 April 1578 – 3 June 1657)[1] was an English physician who made influential contributions to anatomy and physiology.

[2] He was the first known physician to describe completely, and in detail, pulmonary and systemic circulation as well as the specific process of blood being pumped to the brain and the rest of the body by the heart (though earlier writers, such as Realdo Colombo, Michael Servetus, and Jacques Dubois, had provided precursors to some of his theories).

At this point, the physician's function consisted of a simple but thorough analysis of patients who were brought to the hospital once a week and the subsequent writing of prescriptions.

[14] The Lumleian lectureship, founded by Lord Lumley and Dr. Richard Caldwell in 1582, consisted in giving lectures for a period of seven years, with the purpose of "spreading light" and increasing the general knowledge of anatomy throughout England.

When the woman returned she was naturally very angry and upset, but Harvey eventually silenced her by stating that he was the King's Physician, sent to discover whether she was a witch, and if she were, to have her apprehended.

During this journey he wrote to Viscount Dorchester: I can complain that by the way we could scarce see a dog, crow, kite, raven or any other bird, or anything to anatomize, only some few miserable people, the relics of the war and the plague where famine had made anatomies before I came.

[30] During the English Civil War a mob of citizen-soldiers opposed to the King entered Harvey's lodgings, stole his goods, and scattered his papers.

The papers consisted of "the records of a large number of dissections ... of diseased bodies, with his observations on the development on insects, and a series of notes on comparative anatomy.

[32] The conflicts of the Civil War soon led King Charles to Oxford, with Harvey attending, where the physician was made "Doctor of Physic" in 1642 and later Warden of Merton College in 1645.

Much better is it oftentimes to grow wise at home and in private, than by publishing what you have amassed with infinite labour, to stir up tempests that may rob you of peace and quiet for the rest of your days.

[35] His will distributed his material goods and wealth throughout his extended family and also left a substantial amount of money to the Royal College of Physicians.

In the course of time the lead enclosing the remains was, from expose and natural decay, so seriously damaged as to endanger its preservation, rendering some repair of it the duty of those interested in the memory of the illustrious discoverer of the circulation of the Blood.

In accordance with this determination the leaden mortuary chest containing the remains of Harvey was repaired, and was, as far as possible, restored to its original state...[37] Published in 1628 in the city of Frankfurt (host to an annual book fair that Harvey knew would allow immediate dispersion of his work), the 72-page Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus contains the mature account of the circulation of the blood.

Opening with a dedication to King Charles I, the quarto has 17 chapters which give a clear and connected account of the action of the heart and the consequent movement of the blood around the body in a circuit.

Having only a tiny lens at his disposal, Harvey was not able to reach the adequate pictures that were attained through such microscopes used by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek; thus he had to resort to theory – and not practical evidence – in certain parts of his book.

For I could neither rightly perceive at first when the systole and when the diastole took place by reason of the rapidity of the movement...[38] This initial thought led Harvey's ambition and assiduousness to a detailed analysis of the overall structure of the heart (studied with fewer hindrances in cold-blooded animals).

A digression to an experiment can be made to this note: using the inactive heart of a dead pigeon and placing upon it a finger wet with saliva, Harvey was able to witness a transitory and yet incontrovertible pulsation.

Here he says, "...in embryos, whilst the lungs are in a state of inaction, performing no function, subject to no movement any more than if they had not been present, Nature uses the two ventricles of the heart as if they formed but one for the transmission of the blood.

"[40] However, the apex of Harvey's work is probably the eighth chapter, in which he deals with the actual quantity of blood passing through the heart from the veins to the arteries.

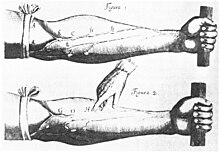

Having this simple but essential mathematical proportion at hand – which proved the overall impossible aforementioned role of the liver – Harvey went on to prove how the blood circulated in a circle by means of countless experiments initially done on serpents and fish: tying their veins and arteries in separate periods of time, Harvey noticed the modifications which occurred; indeed, as he tied the veins, the heart would become empty, while as he did the same to the arteries, the organ would swell up.

Harvey knew that he was facing an uphill battle: But what remains to be said about the quantity and source of the blood which thus passes, is of so novel and unheard-of character that I not only fear injury to myself from the envy of a few, but I tremble lest I have mankind at large for my enemies, so much doth want and custom, that become as another nature, and doctrine once sown and that hath struck deep root, and respect for antiquity, influence all men : still the die is cast, and my trust is in my love of truth, and the candour that inheres in cultivated minds.Harvey's premonitions[45] that his discovery would be met with scepticism, derision, and abuse, were entirely justified.

Arabic scholar Ibn al-Nafis had disputed aspects of Galen's views, providing a model that seems to imply a form of pulmonary circulation in his Commentary on Anatomy in Avicenna's Canon (1242).

[46] Harvey's discoveries inevitably and historically came into conflict with Galen's teachings and the publication of his treatise De Motu Cordis incited considerable controversy within the medical community.

Independently of Ibn Al-Nafis, Michael Servetus identified pulmonary circulation, but this discovery did not reach the public because it was written down for the first time in the Manuscript of Paris in 1546.

[52][53][54] Pulmonary circulation was described by Renaldus Columbus, Andrea Cesalpino and Vesalius, before Harvey would provide a refined and complete description of the circulatory system.

[57][58] The Royal College of Physicians of London holds an annual lecture established by William Harvey in 1656 called the Harveian Oration.

[60] The Harvey Society, found in 1905, is based in New York City and hosts an annual lecture series on recent advances in biomedical sciences.

[61] The main lecture theatre of the School of Clinical Medicine, University of Cambridge is named after William Harvey, who was an alumnus of the institute.

[64] Harvey was seen as a "...humorous but extremely precise man...",[65] and that he was often so immersed in his own thoughts that he would often suffer from insomnia (cured with a simple walk through the house), and how he was always ready for an open and direct conversation.

A heavy drinker of coffee, Harvey would walk out combing his hair every morning full of energy and enthusiastic spirit through the fields.