William O'Brien (judge)

Elrington Ball regarded him as a fine criminal lawyer: Maurice Healy by contrast thought that he was rather lazy, with the traditional barrister's fault of arguing a case without having read his brief properly.

[1] Even his glowing obituary in the Law Times admitted that he had not been highly thought of as a barrister, and it was believed that he owed his appointment to the influence of his friend the Lord Chancellor of Ireland, Sir Edward Sullivan, 1st Baronet, who was almost all-powerful in the choice of judges.

[4] On 6 May 1882 the newly arrived Chief Secretary for Ireland, Lord Frederick Cavendish, went for a walk in Phoenix Park, near his official residence, with Thomas Burke, the long-serving Under-Secretary.

[5] The police were criticised in the press for conducting a dilatory investigation, but in fact, Superintendent John Mallon, who was in charge of the case, quickly learned the identity of the killers through his network of informers, and within a few months arrested all of them, together with a number of accessories to the crime.

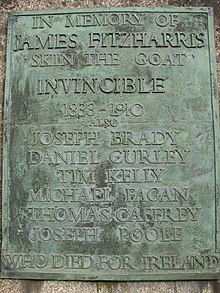

[7] In a lengthy series of trials beginning on 11 April 1883 Joe Brady, Tim Kelly, Dan Corley, Thomas Caffrey and Michael Fagan were tried and convicted for murder; all were subsequently hanged.

[8] The driver of the cab, James Fitzharris (nicknamed Skin-the-Goat) was acquitted of murder but served a prison sentence as an accessory, as did Patrick Delaney, the would-be assassin of Mr. Justice Lawson, and several others.

Since Healy was extremely proud of the overall quality of the Irish judiciary in his youth, it is interesting that he made an exception for O'Brien, whom he called "a man who worked more injustice in his daily round that the reader would believe possible".

[10] In civil cases, though less biased, he was impatient and argumentative, but since most senior members of the Bar, at a time when barristers prided themselves on their frankness, had no respect for him he was unable to impose his authority in Court.

[10] Francis Elrington Ball, in his definitive study of the pre-Independence Irish judiciary, gives a shorter but much more favourable view of O'Brien, whom he regarded as a good lawyer, and also a man of courage who was prepared to put his life in danger by presiding at the Phoenix Park trials.