William Orpen

Major Sir William Newenham Montague Orpen, KBE, RA, RHA (27 November 1878 – 29 September 1931) was an Irish artist who mainly worked in London.

His connections to the senior ranks of the British Army allowed him to stay in France longer than any of the other official war artists, and although he was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the 1918 Birthday Honours, and also elected a member of the Royal Academy of Arts, his determination to serve as a war artist cost him both his health and his social standing in Britain.

[1] After his early death a number of critics, including other artists, were loudly dismissive of Orpen's work, and for many years his paintings were rarely exhibited, a situation that only began to change in the 1980s.

[5] During his six years at the college, he won every major prize there, plus the British Isles gold medal for life drawing, before leaving to study at the Slade School of Art between 1897 and 1899.

[7] Orpen's The Mirror, shown at the NEAC in 1900, references both Jan van Eyck's Arnolfini Portrait of 1434 and also elements of seventeenth-century Dutch interiors, such as muted tones and deep shadows.

Between 1908 and 1912, Orpen and his family spent the summer on the coast at Howth, north of Dublin, where he began painting in the open air and developed a distinctive plein-air style that featured figures composed of touches of colour without a drawn outline.

[16][17] John Singer Sargent promoted Orpen's work and he soon built a lucrative reputation, in both London and Dublin, for painting society portraits.

Mrs St. George, (1912), and Lady Rocksavage (1913), both demonstrate Orpen's ability to produce the swagger portraits that Edwardian high society greatly valued.

Throughout 1916 Orpen continued painting portraits, most notably one of a despondent Winston Churchill,[21] but soon started using both his own contacts and those of Evelyn Saint-George, to secure a war artist posting.

An officer from Kensington Barracks was appointed as his military aide, a car and driver were made available in France and Orpen paid for a batman and assistant to accompany him.

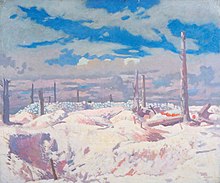

Each day Orpen would be driven to locations such as Thiepval, Beaumont-Hamel or Ovillers-la-Boisselle to sketch Allied troops or German prisoners and record the devastation left by the Battle of the Somme amid the frozen and desolate landscape.

In May 1917, he painted portraits of both Haig and Sir Hugh Trenchard, the commander of the Royal Flying Corps, and both of these images were widely reproduced in British newspapers and magazines.

Throughout the summer of 1917, other than Orpen and his driver and assistant, the only people on the empty battlefield around Thiepval were the British and Allied burial parties working to identify and inter the thousands of bodies left in the open or in abandoned trenches and dugouts.

Amid the derelict trenches, Orpen claimed to have encountered soldiers who had been traumatised and shell-shocked by the fighting and made, at least, two paintings, A Man with a Cigarette and Blown Up, Mad, based on these meetings.

His portrait of Lieutenant Reginald Hoidge, MC and Bar, was painted a few hours after the young pilot had been in a dogfight and Orpen was greatly impressed by his calmness.

[2] Rhys-Davids was killed in combat within a week of sitting for Orpen, whose portrait of him was used as the cover illustration of the next edition of War Pictorial magazine and widely reproduced elsewhere after that.

Lee made it clear that if the title was intended as a joke it was in very bad taste coming so soon after the execution of Mata Hari but if the subject really was a spy then Orpen could be facing a court-martial.

[27] Orpen gave Lee a fantastical story that the woman in the picture was a German spy who had been executed by the French but who, in an attempt to save herself, had at the last moment revealed herself naked in front of the firing squad.

Not only had Lee been the brigade major sent to Dublin to put down the 1916 Easter Rising, but had been the officer in charge of arranging several of the executions that followed the fighting, including that of Joseph Plunkett, the husband of Grace Gifford, Orpen's star pupil from his teaching days.

Highlights of the exhibition included nine of Orpen's 'khaki portraits' and several of his works from the Somme such as Highlander Passing a Grave and Thinker on the Butte de Warlencourt.

[32] In fact Arthur Lee had refused to pass nearly all of the paintings shown at Agnew's but Orpen appealed to the Director of Military Intelligence, General George Macdonogh, and had him overruled.

[1] Orpen returned to France in July and spent a second summer painting on the old Somme battlefield and making frequent trips to Paris to complete a series of portraits of Canadian commanders.

In Harvest (1918), which shows women tending a grave covered in barbed wire, he used a garish palette of colours to emphasize the unreal nature of the scene.

[2] In November 1918, Orpen collapsed and became seriously ill. Yvonne Aubicq spent two months nursing him before he moved to Paris in January 1919 to begin work on his next commission.

[37][38] Orpen considered that the whole conference was being conducted with a lack of respect or regard for the suffering of the soldiers who fought in the war, and he attempted to address this in the third painting of the commission.

Among the delegates, Orpen included two additional figures, a Grenadier Guards sergeant and Arthur Rhys-Davids, the young fighter pilot he had painted the week before he was killed in 1917.

Orpen did receive some letters of appreciation from ex-servicemen and from family members of soldiers who had died in the war, but he still felt the need to issue a statement explaining the picture and his intentions.

[6] In 1927, Orpen accepted a commission to paint a portrait of David Lloyd George but the completed work was rejected as being too informal for such a senior politician.

[22][25] Bruce Arnold noted Orpen's interest in self-portraiture: his self-portraits are often searching and dramatic and seem to meet a deep personal need for frequent self-analysis.

[6] Bruce Arnold's 1981 biography revived interest in Orpen among scholars, and in 2005 a major retrospective which also included his peacetime work was held at the Imperial War Museum, and led to a reappraisal of his place in British and Irish culture.