William T. R. Fox

He was a pioneer in establishing international relations, and the systematic study of statecraft and war, as a major academic discipline.

[6] The director there, Frederick S. Dunn – who held that international relations was "politics in the absence of central authority" – was another important influence on Fox.

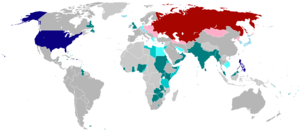

[5] Fox coined the word "superpower" in his 1944 book The Super-Powers: The United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union – Their Responsibility for Peace to identify a new category of power able to occupy the highest status in a world in which, as the war then raging demonstrated, states could challenge and fight each other on a global scale.

The book forecast the directions that Soviet-American relations would take if the powers did not collaborate, but also made an effort to explore feasible opportunities that leaders might have to forestall that future.

[2][7] He was one of the contributors to Bernard Brodie's landmark 1946 volume The Absolute Weapon: Atomic Power and World Order, where he recognized with Brodie that the future nuclear stand-off between the U.S. and U.S.S.R. would become focused on the fear of mutual destruction, but in his portion explored ways that international agreements to limit or control nuclear weapons might improve matters.

Fox came away from his activities during this period convinced that the framing of international relations theory should be around the proposition that, "If man is to have the opportunity to exercise some measure of rational control over his destiny, the limits of the possible and the consequences of the desirable both have to be investigated.

[9] Upon the request of President of Columbia Dwight D. Eisenhower,[9] in 1951 Fox became the first director of the university's Institute of War and Peace Studies, a position he would hold for 25 years.

[16] Fox also worked on behalf of the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, addressing issues related to the security of Western Europe.

In a 1967 address to one of the World Affairs Councils of America, Fox said that NATO "seems superfluous because it is working ... it is in part a victim of its own success.

"[17] During his career, Fox described himself as a "pragmatic meliorist" who believed in the possibility of improving how international relations were conducted and in highlighting the normative meanings of domestic and world policies.

In her essay, Professor Elizabeth C. Hanson said that, "Bill Fox helped to shape international relations as a major academic field and to demonstrate the relevance of its theoretical investigations to policy making.

"[6] She went on to describe his contributions as a professor and colleague, writing that, "Fox's influence as teacher and mentor on the discipline of international relations was enormous.

[12] In other settings, the scholar Lucja Swiatkowski Cannon wrote that Fox "was a U.S. pioneer in establishing the systematic study of statecraft and war as an academic discipline.

"[21] Another scholar, James McAllister, noted that Fox's influence at Columbia's Institute of War and Peace Studies was being felt well after his death.