William of Tyre

As he was involved in the dynastic struggle that developed during Baldwin IV's reign, his importance waned when a rival faction gained control of royal affairs.

[7] Around 1145 William went to Europe to continue his education in the schools of France and Italy, especially in those of Paris and Bologna, "the two most important intellectual centers of twelfth-century Christendom.

[9] William studied liberal arts and theology in Paris and Orléans for about ten years, with professors who had been students of Thierry of Chartres and Gilbert de la Porrée.

[11] William's list of professors "gives us almost a who's who of the grammarians, philosophers, theologians, and law teachers of the so-called Twelfth-Century Renaissance", and shows that he was as well-educated as any European cleric.

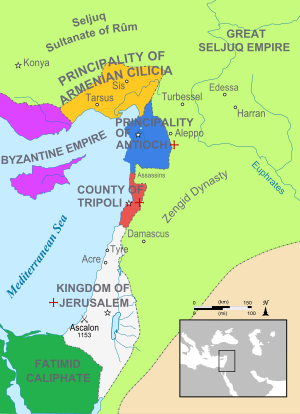

Amalric turned towards Egypt because Muslim territory to the east of Jerusalem had fallen under the control of the powerful Zengid sultan Nur ad-Din.

In 1167 Amalric married Maria Comnena, grand-niece of Byzantine emperor Manuel I Comnenus, and in 1168 the king sent William to finalize a treaty for a joint Byzantine-crusader campaign against Egypt.

"The other boys gave evidence of pain by their outcries," wrote William, "but Baldwin, although his comrades did not spare him, endured it altogether too patiently, as if he felt nothing ...

The "court party" was led by Baldwin's mother, Amalric's first wife Agnes of Courtenay, and her immediate family, as well as recent arrivals from Europe who were inexperienced in the affairs of the kingdom and were in favour of war with Saladin.

Peter W. Edbury, however, has more recently argued that William must be considered extremely partisan as he was naturally allied with Raymond, who was responsible for his later advancement in political and religious offices.

[19] The general consensus among recent historians is that although there was a dynastic struggle, "the division was not between native barons and newcomers from the West, but between the king's maternal and paternal kin.

In 1177 he performed the funeral services for William of Montferrat, husband of Baldwin IV's sister Sibylla, when the patriarch of Jerusalem, Amalric of Nesle, was too sick to attend.

At Easter in 1180, the two factions were divided even further when Raymond and his cousin Bohemond III of Antioch attempted to force Sibylla to marry Baldwin of Ibelin.

According to {{Q{11815922}} and John Rowe, the obscurity of William's life during these years shows that he did not play a large political role, but concentrated on ecclesiastical affairs and the writing of his history.

[28] William remained in the kingdom and continued to write up until 1184, but by then Jerusalem was internally divided by political factions and externally surrounded by the forces of Saladin, and "the only subjects that present themselves are the disasters of a sorrowing country and its manifold misfortunes, themes which can serve only to draw forth lamentations and tears.

Saladin defeated King Guy at the Battle of Hattin in 1187, and went on to capture Jerusalem and almost every other city of the kingdom, except the seat of William's archdiocese, Tyre.

For, as the series of events seemed to require, we have included in this study on which we are now engaged many details about the characters, lives, and personal traits of kings, regardless of whether these facts were commendable or open to criticism.

The first book begins with the conquest of Syria by Umar in the seventh century, but otherwise the work deals with the advent of the First Crusade and the subsequent political history of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Much of the Historia was finished before William left to attend the Lateran Council, but new additions and corrections were made after his return in 1180, perhaps because he now realized that European readers would also be interested in the history of the kingdom.

[38] Alan V. Murray, however, has argued that, at least for the accounts of Persia and the Turks in his chronicle, William relied on Biblical and earlier medieval legends rather than actual history, and his knowledge "may be less indicative of eastern ethnography than of western mythography.

"[39] William had access to the chronicles of the First Crusade, including Fulcher of Chartres, Albert of Aix, Raymond of Aguilers, Baldric of Dol, and the Gesta Francorum, as well as other documents located in the kingdom's archives.

[51] William was famously biased against the Knights Templar, whom he believed to be arrogant and disrespectful of both secular and ecclesiastical hierarchies, as they were not required to pay tithes and were legally accountable only to the Pope.

[52] William accused them of hindering the siege of Ascalon in 1153; of poorly defending a cave-fortress in 1165, for which twelve Templars were hanged by King Amalric; of sabotaging the invasion of Egypt in 1168; and of murdering Assassin ambassadors in 1173.

The end of the Historia coincides with the massacre of the Latins in Constantinople and the chaos that followed the coup of Andronicus I Comnenus, and in his description of those events, William was certainly not immune to the extreme anti-Greek rhetoric that was often found in Western European sources.

In the 13th century, James of Vitry had access to a copy while he was bishop of Acre, and it was used by Guy of Bazoches, Matthew Paris, and Roger of Wendover in their own chronicles.

[59] In England, however, the Historia was expanded in Latin, with additional information from the Itinerarium Regis Ricardi, and the chronicle of Roger Hoveden; this version was written around 1220.

The now-standard Latin critical edition, based on six of the surviving manuscripts, was published as Willelmi Tyrensis Archiepiscopi Chronicon in the Corpus Christianorum in 1986, by R. B. C. Huygens, with notes by Hans E. Mayer and Gerhard Rösch.

The translation was sometimes called the Livre dou conqueste; it was known by this name throughout Europe as well as in the crusader Kingdom of Cyprus and in Cilician Armenia, and 14th-century Venetian geographer Marino Sanuto the Elder had a copy of it.

Vessey believes that William's claim to have been commissioned by Amalric is a typical ancient and medieval topos, or literary theme, in which a wise ruler, a lover of history and literature, wishes to preserve for posterity the grand deeds of his reign.

In the mid twentieth century, Marshall W. Baldwin,[72] Steven Runciman,[73] and Hans Eberhard Mayer[74] were influential in perpetuating this point of view, although the more recent re-evaluations of this period by Vessey, Peter Edbury and Bernard Hamilton have undone much of William's influence.

[81] As the Dictionary of the Middle Ages says, "William's achievements in assembling and evaluating sources, and in writing in excellent and original Latin a critical and judicious (if chronologically faulty) narrative, make him an outstanding historian, superior by medieval, and not inferior by modern, standards of scholarship.