Wind power in Ireland

[5] Concerns over energy security (Ireland has an estimated 15.4m tonnes of coal reserves, peat bogs, offshore oil and gas fields, and has extensive wind resources), climate change mitigation policies, and compliance with EU Directives for market liberalization, have all shaped wind power development in Ireland.

[citation needed] State financial support for the national electricity sector, and particular technologies, has been influenced by a slow move towards liberalization, and concerns for energy security and climate change mitigation.

[7] Ireland uses an industry subsidy known as the Public Service Obligation (PSO) to support the generation of electricity from sustainable, renewable and indigenous sources, including wind.

[citation needed] The PSO levy funds the government's main mechanisms to support the generation of electricity from sustainable, renewable and indigenous sources.

This problem was addressed by the Planning and Development (Amendment) Act 2010, which introduced Section 28, allowing a one-off extension of up to 5 years if "there were considerations of a commercial, economic, or technical nature beyond the control of the applicant, which substantially militated against either the commencement of development or the carrying out of substantial works pursuant to the planning permission."

[citation needed] The fourth issue regarding the generation of wind power is the Renewable Energy Feed-in Tariff, or REFIT.

[27] Building wind turbines and access roads on top of peatland results in the drainage and then eventual oxidation of some of the peat.

[29] Biochemist Mike Hall said in 2009; "wind farms (built on peat bogs) may eventually emit more carbon than an equivalent coal-fired power station" if drained.

[37] Following the Corrie Mountain bog burst of 2008, Ireland was fined by a European Court over its mishandling of wind farms on peatland.

[42] Some on-land wind farms in Ireland have been opposed by local residents, county councils, the Heritage Council and An Taisce (The National Trust) for their potential to blight the landscape, and having a harmful impact on protected scenic areas, archaeological landscapes, tourism and cultural heritage.

In 2014, more than 100 protest groups united against government plans to build thousands of wind turbines in the Midlands to export energy to Britain.

Among other things, they argued the wind farms would ruin the landscape and mainly benefit "multinational corporations who are sucking subsidies from the UK taxpayers".

[43][44][45] In 2021, a proposed wind farm at Kilranelagh in the Wicklow Mountains was refused as it would have harmed the area's archaeological landscape, which includes the Baltinglass hillfort complex.

[46] An application to build a wind farm overlooking the scenic valley of Gougane Barra was refused by Cork County Council, who voted unanimously against it.

The company appealed to An Bord Pleanála, whose inspector also rejected it, stating it "would have significant adverse environmental and visual impacts and is not sustainable at this highly sensitive location".

Despite this, An Bord Pleanála granted permission, on the grounds that the wind farm would contribute "to the implementation of Ireland's national strategic policy on renewable energy".

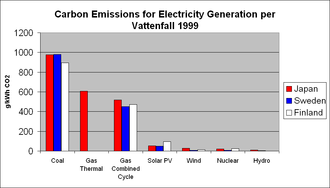

[47] In a typical study of a wind farms Life cycle assessment (LCA), in isolation, it usually results in similar findings as the following 2006 analysis of 3 installations in the US Midwest, were the carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions of wind power ranged from 14 to 33 metric ton per GWh (14 - 33 g CO2/kWh) of energy produced, with most of the CO2 emissions coming from the production of concrete for wind-turbine foundations.

[55] These findings were of relatively "low [emission] savings", as presented in the Journal of Energy Policy, and were largely due to an over-reliance on the results from the analysis of wind farms LCAs in isolation.

A study conducted by Pehnt and colleagues (2008) reports that a moderate level of [grid] wind penetration (12%) would result in efficiency penalties of 3% to 8%, depending on the type of conventional power plant considered.

Gross and colleagues (2006) report similar results, with efficiency penalties ranging from nearly 0% to 7% for up to 20% [of grid] wind penetration.

While the more dependable alpine Hydro power and nuclear stations have median total life cycle emission values of 24 and 12 g CO2-eq/kWh respectively.

[61] This acceptable level of renewable penetration was found in what the study called Scenario 5, provided 47% of electrical capacity (different from demand) with the following mix of renewable energies: The study cautions that various assumptions were made that "may have understated dispatch restrictions, resulting in an underestimation of operational costs, required wind curtailment, and CO2 emissions" and that "The limitations of the study may overstate the technical feasibility of the portfolios analyzed..." Scenario 6, which proposed renewables providing 59% of electrical capacity and 54% of demand had problems.

The study chose not to analyze the cost-effectiveness of the required changes, stating that "determination of costs and benefits had become extremely dependent on the assumptions made," and that this uncertainty could have impacted the robustness of the results.