Winghead shark

Reaching a length of 1.9 m (6.2 ft), this small brown to gray shark has a slender body with a tall, sickle-shaped first dorsal fin.

The wide spacing of its eyes grants superb binocular vision, while the extremely long nostrils on the leading margin of the cephalofoil may allow for better detection and tracking of odor trails in the water.

The cephalofoil also provides a large surface area for its ampullae of Lorenzini and lateral line, with potential benefits for electroreception and mechanoreception, respectively.

Inhabiting the shallow coastal waters of the central and western Indo-Pacific, the winghead shark feeds on small bony fishes, crustaceans, and cephalopods.

Females produce annual litters of six to 25 pups; depending on region, birth may occur from February to June after a gestation period of 8–11 months.

French zoologist Georges Cuvier, as a brief footnote to the account of S. zygaena in his 1817 Le Règne animal distribué d'après son organisation, pour servir de base à l'histoire naturelle des animaux et d'introduction à l'anatomie comparée, observed that Bloch's specimen (which he labeled "z. nob.

[4][5] In 1862, Theodore Gill placed the winghead shark in its own genus Eusphyra, derived from the Greek eu ("good" or "true") and sphyra ("hammer").

Eusphyra was resurrected by Henry Bigelow and William Schroeder in 1948, and came into wider usage after additional taxonomic research was published by Leonard Compagno in 1979 and 1988.

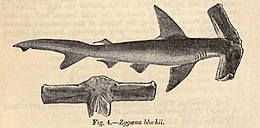

[8][9][10] True to its name, the winghead shark's cephalofoil consists of a pair of long, narrow, and gently swept-back blades.

[11] The winghead shark is found in the tropical central and western Indo-Pacific, from the Persian Gulf eastward across South and Southeast Asia to New Guinea and northern Queensland.

The placement of the eyes at the ends of the cephalofoil provides a binocular field of view of 48°, the most of any hammerhead and four times that of a requiem shark; this species thus has excellent depth perception, which may aid in hunting.

Another potential olfactory benefit of the cephalofoil is increased separation between the midpoints of the left and right nostrils, which enhances the shark's ability to resolve the direction of a scent trail.

[15] Finally, the cephalofoil may increase the shark's ability to detect the electric fields and movements of its prey, by providing a larger surface area for its electroreceptive ampullae of Lorenzini and mechanoreceptive lateral line.

At a length of 20–29 cm (7.9–11.4 in), the placenta has formed; the first teeth, dermal denticles, and skin pigmentation appear on the embryo, and the external gills are much reduced in size.

[30] Harmless to humans, the winghead shark is caught throughout its range using gillnets, seines, stake nets, longlines, and hook-and-line.

[3][5] This species is taken in large numbers in some areas, such as in the Gulf of Thailand and off India and Indonesia, and anecdotal evidence indicates its population has suffered as a result.