Electrical wiring

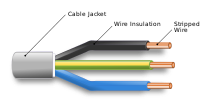

Allowable wire and cable types and sizes are specified according to the circuit operating voltage and electric current capability, with further restrictions on the environmental conditions, such as ambient temperature range, moisture levels, and exposure to sunlight and chemicals.

Associated circuit protection, control, and distribution devices within a building's wiring system are subject to voltage, current, and functional specifications.

The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) is attempting to harmonise wiring standards among member countries, but significant variations in design and installation requirements still exist.

In a light commercial environment, more frequent wiring changes can be expected, large apparatus may be installed and special conditions of heat or moisture may apply.

Heavy industries have more demanding wiring requirements, such as very large currents and higher voltages, frequent changes of equipment layout, corrosive, or wet or explosive atmospheres.

In facilities that handle flammable gases or liquids, special rules may govern the installation and wiring of electrical equipment in hazardous areas.

Special versions of non-metallic sheathed cables, such as US Type UF, are designed for direct underground burial (often with separate mechanical protection) or exterior use where exposure to ultraviolet radiation (UV) is a possibility.

Building wire conductors larger than 10 AWG (or about 5 mm2) are stranded for flexibility during installation, but are not sufficiently pliable to use as appliance cord.

Tables in electrical safety codes give the maximum allowable current based on size of conductor, voltage potential, insulation type and thickness, and the temperature rating of the cable itself.

[citation needed] Unlike copper, aluminium has a tendency to creep or cold-flow under pressure, so older plain steel screw clamped connections could become loose over time.

This is sometimes addressed by coating aluminium conductors with an antioxidant paste (containing zinc dust in a low-residue polybutene base[6]) at joints, or by applying a mechanical termination designed to break through the oxide layer during installation.

While larger sizes are still used to feed power to electrical panels and large devices, aluminium wiring for residential use has acquired a poor reputation and has fallen out of favour.

This can compensate for the higher resistance and lower mechanical strength of aluminium, meaning the larger cross sectional area is needed to achieve comparable current capacity and other features.

This may be a specialised bendable pipe, called a conduit, or one of several varieties of metal (rigid steel or aluminium) or non-metallic (PVC or HDPE) tubing.

Rectangular cross-section metal or PVC wire troughs (North America) or trunking (UK) may be used if many circuits are required.

In cases where safety-critical wiring must be kept operational during an accidental fire, fireproofing must be applied to maintain circuit integrity in a manner to comply with a product's certification listing.

Local electrical regulations may restrict or place special requirements on mixing of voltage levels within one cable tray.

Each live ("hot") conductor of such a system is a rigid piece of copper or aluminium, usually in flat bars (but sometimes as tubing or other shapes).

Open bus bars are never used in publicly accessible areas, although they are used in manufacturing plants and power company switch yards to gain the benefit of air cooling.

This assembly, known as bus duct or busway, can be used for connections to large switchgear or for bringing the main power feed into a building.

[further explanation needed] For very large currents in generating stations or substations, where it is difficult to provide circuit protection, an isolated-phase bus is used.

This type of bus can be rated up to 50,000 amperes and up to hundreds of kilovolts (during normal service, not just for faults), but is not used for building wiring in the conventional sense.

[citation needed] Squirrels, rats, and other rodents may gnaw on unprotected wiring, causing fire and shock hazards.

[citation needed] The first interior power wiring systems used conductors that were bare or covered with cloth, which were secured by staples to the framing of the building or on running boards.

Underground conductors were insulated with wrappings of cloth tape soaked in pitch, and laid in wooden troughs which were then buried.

By arranging wires on opposite sides of building structural members, some protection was afforded against short-circuits that can be caused by driving a nail into both conductors simultaneously.

In the United Kingdom, an early form of insulated cable,[9] introduced in 1896, consisted of two impregnated-paper-insulated conductors in an overall lead sheath.

Paper-insulated cables proved unsuitable for interior wiring installations because very careful workmanship was required on the lead sheaths to ensure moisture did not affect the insulation.

[11] Armored cables with two rubber-insulated conductors in a flexible metal sheath were used as early as 1906, and were considered at the time a better method than open knob-and-tube wiring, although much more expensive.

When switches, socket outlets or light fixtures are replaced, the mere act of tightening connections may cause hardened insulation to flake off the conductors.