Witch trials in early modern Scotland

He became interested in witchcraft and published a defence of witch-hunting in the Daemonologie in 1597, but he appears to have become increasingly sceptical and eventually took steps to limit prosecutions.

The hunts subsided under English occupation after the Civil Wars during the period of the Commonwealth led by Oliver Cromwell in the 1650s, but returned after the Restoration in 1660, causing some alarm and leading to the Privy Council of Scotland limiting arrests, prosecutions and torture.

High-profile political cases included the action against John Stewart, Earl of Mar for allegedly using sorcery against his brother King James III in 1479.

[6] From the late sixteenth century attitudes began to change, and witches were seen as deriving powers from the Devil, with the result that witchcraft was seen as a form of heresy.

[4] The first witch-hunt under the act was in the east of the country in 1568–69 in Angus and the Mearns,[7] where there were unsuccessful attempts to introduce elements of the diabolic pact and the hunt collapsed.

"[9] James VI's visit to Denmark in 1589, where witch-hunts were already common, may have encouraged an interest in the study of witchcraft, and he came to see the storms he encountered on his voyage as the result of magic.

Several people, most notably Agnes Sampson and the schoolmaster John Fian, were convicted of using witchcraft to send storms against James' ship.

He subsequently believed that his cousin, the nobleman Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell, was a witch, and after the latter fled in fear of his life, he was outlawed as a traitor.

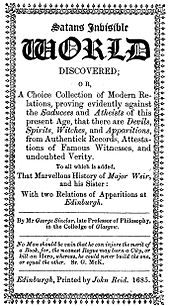

[13] Inspired by his personal involvement, in 1597 he wrote the Daemonologie, a tract that opposed the practice of witchcraft and which provided background material for Shakespeare's Tragedy of Macbeth, which contains probably the most famous literary depiction of Scottish witches.

In the view of Thomas Lolis, James I's goal was to divert suspicion away from male homosociality among the elite, and focus fear on female communities and large gatherings of women.

[14] However, after the publication of Daemonologie his views became more sceptical,[15] and in the same year he revoked the standing commissions on witchcraft, limiting prosecutions by the central courts.

[17] Large series of trials included those in 1590–91 and the Great Scottish Witch Hunt of 1597, which took place across Scotland from March to October.

[20] After the revocation of the standing commissions in 1597, the pursuit of witchcraft was largely taken over by kirk sessions, disciplinary committees run by the parish elite, and was often used to attack "superstitious" and Catholic practices.

[2] Scottish witchcraft trials were notable for their use of pricking,[3] in which a suspect's skin was pierced with needles, pins and bodkins as it was believed that they would possess a Devil's mark through which they could not feel pain.

[23] Judicial torture was used in some high-profile cases, like that of John Fine, one of the witches accused of plotting the death of the king in 1590, whose feet were crushed in a shin press, known as the boots.

Margaret Bane, a midwife, it was claimed, could transfer the pains of childbirth to a woman's husband and Helen Gray cast a spell on a man that gave him a permanent erection.

These included by reading the marks on the shoulder blade of a slaughtered animal, measuring a person's sleeve or waist to see if they were suffering from a fever, or being able to find answers based on which way a sieve suspended from scissors or shears swung, as Margaret Mungo was accused of doing, before the kirk session of Dingwall in 1649.

Isobel Gowdie, the young wife of a cottar from near Auldearn, who was tried for witchcraft in 1662, left four depositions, gained without torture, that provide one of the most detailed insights into magical beliefs in Britain.

[2] Prosecutions began to decline as trials were more tightly controlled by the judiciary and government, torture was more sparingly used and standards of evidence were raised.

[2] There may also have been a growing popular scepticism, and, with relative peace and stability, the economic and social tensions that may have contributed to accusations were reduced, although there were occasional local outbreaks, like those in East Lothian in 1678 and in Paisley in 1697.

Older theories, that there was a widespread pagan cult that was persecuted in this period and that the witch-hunts were the result of a rising medical profession eliminating folk healers, have been discredited among professional historians.

[40] Christina Larner suggested that the outbreak of the hunt in the mid-sixteenth century was tied to the rise of a "godly state", where the reformed Kirk was closely linked to an increasingly intrusive Scottish crown and legal system.

However, Brian P. Levack argues that the Scottish system was only partly inquisitorial and that use of judicial torture was extremely limited, similar to the situation in England.

[41] The diabolic pact is often stated as a major difference between Scottish and English witchcraft cases, but Stuart Maxwell argues that the iconography of Satan may be an imposition of central government beliefs on local traditions, particularly those concerned with fairies, which were more persistent in Scotland than in England.

[43] On the International Women's Day in 2022, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon officially apologized on behalf of the Scottish government to those accused under the Witchcraft Act.