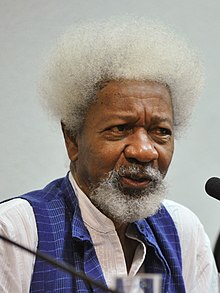

Wole Soyinka

[16] Later in 1954, Soyinka relocated to England, where he continued his studies in English literature, under the supervision of his mentor Wilson Knight at the University of Leeds (1954–57).

degree, Soyinka began publishing and working as editor for a satirical magazine called The Eagle; he wrote a column on academic life, in which he often criticised his university peers.

His first major play, The Swamp Dwellers (1958), was followed a year later by The Lion and the Jewel, a comedy that attracted interest from several members of London's Royal Court Theatre.

After its fifth issue (November 1959), Soyinka replaced Jahnheinz Jahn to become coeditor for the literary periodical Black Orpheus (its name derived from a 1948 essay by Jean-Paul Sartre, "Orphée Noir", published as a preface to Anthologie de la nouvelle poésie nègre et malgache, edited by Léopold Senghor).

Entitled My Father's Burden and directed by Segun Olusola, the play was featured on the Western Nigeria Television (WNTV) on 6 August 1960.

[27][28] Soyinka published works satirising the "Emergency" in the Western Region of Nigeria, as his Yorùbá homeland was increasingly occupied and controlled by the federal government.

[29] With the Rockefeller grant, Soyinka bought a Land Rover, and he began travelling throughout the country as a researcher with the Department of English Language of the University College in Ibadan.

In an essay of the time, he criticised Leopold Senghor's Négritude movement as a nostalgic and indiscriminate glorification of the black African past that ignores the potential benefits of modernisation.

But in fact, Soyinka wrote in a 1960 essay for the Horn: "The duiker will not paint 'duiker' on his beautiful back to proclaim his duikeritude; you'll know him by his elegant leap.

In November that year, The Trials of Brother Jero and The Strong Breed were produced in the Greenwich Mews Theatre in New York City.

[46] While still imprisoned, Soyinka translated from Yoruba a fantastical novel by his compatriot D. O. Fagunwa, entitled The Forest of a Thousand Demons: A Hunter's Saga.

Two films about this period of his life have been announced: The Man Died, directed by Awam Amkpa, a feature film based on a fictionalized form of Soyinka's 1973 prison memoirs of the same name;[47][48] and Ebrohimie Road, written and directed by Kola Tubosun, which takes a look at the house where Soyinka lived between 1967 – when he arrived back in Ibadan to take on the directorship of the School of Drama – and 1972, when he left for exile after being released from prison.

[53] In April 1971, concerned about the political situation in Nigeria, Soyinka resigned from his duties at the University in Ibadan, and began years of voluntary exile.

After the political turnover in Nigeria and the subversion of Gowon's military regime in 1975, Soyinka returned to his homeland and resumed his position as Chair of Comparative Literature at the University of Ife.

In October, the French version of The Dance of The Forests was performed in Dakar, while in Ife, his play Death and The King's Horseman premièred.

In July, one of his musical projects, the Unlimited Liability Company, issued a long-playing record entitled I Love My Country, on which several prominent Nigerian musicians played songs composed by Soyinka.

Soyinka's speech was an outspoken criticism of apartheid and the politics of racial segregation imposed on the majority by the National South African government.

In October 1994, he was appointed UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador for the Promotion of African culture, human rights, freedom of expression, media and communication.

That same year, a BBC-commissioned play called Document of Identity aired on BBC Radio 3, telling the lightly-fictionalized story of the problems his daughter's family encountered during a stopover in Britain when they fled Nigeria for the US in 1996; her son, Oseoba Airewele was born in Luton and became a stateless person.

[79] In April 2007, Soyinka called for the cancellation of the Nigerian presidential elections held two weeks earlier, beset by widespread fraud and violence.

[80] In the wake of the attempting bombing on a Northwest Airlines flight to the United States by a Nigerian student who had become radicalised in Britain, Soyinka questioned the British government's social logic in allowing every religion to openly proselytise their faith, asserting that it was being abused by religious fundamentalists, thereby turning England into, in his view, a cesspit for the breeding of extremism.

"[88] September 2021 saw the publication of Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth, Soyinka's first novel in almost 50 years, described in the Financial Times as "a brutally satirical look at power and corruption in Nigeria, told in the form of a whodunnit involving three university friends.

"[95]Around July 2023, Soyinka came under severe criticism, after writing an open letter to the Emir of Ilorin, Ibrahim Sulu-Gambari, over the cancellation of the Isese festival proposed by an Osun priestess, Omolara Olatunji.

[102] In 2014, the collection Crucible of the Ages: Essays in Honour of Wole Soyinka at 80, edited by Ivor Agyeman-Duah and Ogochwuku Promise, was published by Bookcraft in Nigeria and Ayebia Clarke Publishing in the UK, with tributes and contributions from Nadine Gordimer, Toni Morrison, Ama Ata Aidoo, Ngugi wa Thiong'o, Henry Louis Gates, Jr, Margaret Busby, Kwame Anthony Appiah, Ali Mazrui, Sefi Atta, and others.

[103][104] In 2018, Henry Louis Gates, Jr tweeted that Nigerian filmmaker and writer Onyeka Nwelue visited him in Harvard and was making a documentary film on Wole Soyinka.

[105] As part of efforts to mark his 84th birthday, a collection of poems titled 84 Delicious Bottles of Wine was published for Wole Soyinka, edited by Onyeka Nwelue and Odega Shawa.

In a book published in 2020, University College London academic Caroline Davis examined archival evidence of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) funding of African authors in the post-independence period.

The book states that even after the CIA's covert role in some of these initiatives was revealed in the 1960s, Soyinka had “unusually close ties to the US government even to the point of frequently meeting with US intelligence in the late 1970s”.

When the book was published Soyinka vociferously denied having been a CIA agent and stated that he would "[follow the authors] to the end of the earth and to the pit of hell until I get a retraction".

[125] Adebajo states that, "Any suggestion that Soyinka was also a pro-American agent would not be borne out by his political activism, which frequently condemned US-supported Cold War clients."