Woman Suffrage Procession

[citation needed] The procession was organized by the suffragists Alice Paul and Lucy Burns for the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

As stated in its official program, the parade's purpose was to "march in a spirit of protest against the present political organization of society, from which women are excluded."

The final act was a rally at the Memorial Continental Hall with prominent speakers, including Anna Howard Shaw and Helen Keller.

[1]: 362 [2] Paul and Burns had seen first-hand the effectiveness of militant activism while working for Emmeline Pankhurst in the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in Britain.

[1]: 365 [4] Paul and Burns found that many suffragists supported the WSPU's militant tactics, including Harriot Stanton Blatch, Alva Belmont, Elizabeth Robins, and Rhetta Child Dorr.

[1]: 377 [15] Paul and Burns persuaded NAWSA to endorse an immense suffrage parade in Washington, D.C., to coincide with newly elected President Woodrow Wilson's inauguration the following March.

[17] Once the board approved the parade in December 1912, it appointed Dora Lewis, Mary Ritter Beard, and Crystal Eastman to the committee, though they all worked outside of Washington.

Per the event program, the stated purpose was to "march in a spirit of protest against the present political organization of society, from which women are excluded.

"[23] The timing of the date for the procession, March 3, was important because incoming president Woodrow Wilson, whose inauguration was to take place the following day, would be put on notice that this would be a key issue during his term.

She requested a permit to march down Pennsylvania Avenue from the Peace Monument to the Treasury Building, then on to the White House before ending at Continental Hall.

[26] District superintendent of police, Major Richard H. Sylvester, offered a permit for Sixteenth Street, which would have taken the procession through a residential area, past several embassies.

Anticipating that most of these people would come to observe the suffrage parade, Paul was concerned about the ability of the local police force to handle the crowd; her disquiet proved to be justified by events.

These ideals were embodied in the selection of the parade's herald, Inez Milholland, a labor lawyer from New York City who had been dubbed "the most beautiful suffragette".

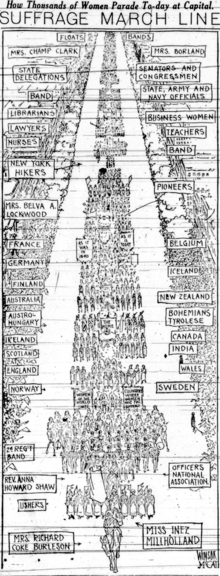

[23]Jane Walker Burleson on horseback, accompanying a model of the Liberty Bell brought from Philadelphia, led the procession as Grand Marshal, immediately followed by the herald, Milholland, on a white horse.

[46] There followed a carefully orchestrated order of professional women, beginning with various nursing groups, the Woman's Christian Temperance Union and the PTA, before finally adding in non-traditional careers such as lawyers, artists, and businesswomen.

Another Lincoln quote was featured at the top of the official program: "I go for all sharing the privilege of the government who assist in bearing its burdens, by no means excluding women."

[50] These scenes were performed by silent actors to portray various attributes of patriotism and civic pride, which both men and women strove to emulate.

[22] By creating this stunning drama, Paul differentiated the American suffrage movement from Britain's "by fully appropriating the best possibilities of nonviolent visual rhetoric" per Adams and Keene.

Sylvester, who was at the train station awaiting Wilson's arrival, heard about the problem and called the cavalry unit on standby at Fort Myers.

Eventually, boys from the Maryland Agricultural College created a human barrier protecting the women from the angry crowd and helping them reach their destination.

Key participants included activist attorney Louis Brandeis (who became a Supreme Court justice in 1916) and Minnesota senator Moses Edwin Clapp.

[61] Alice Paul and the Congressional Union asked President Wilson to push Congress for a federal amendment, beginning with a deputation to the White House shortly after the parade and in several additional visits.

[63] When asked if it had been unwise for her to push Wilson for his stance on woman's suffrage, Paul responded that it was important to make the public aware of his position so they could use it against him when the time came to put pressure on the Democrats during an election.

[1][68] The demonstration on Pennsylvania Avenue was the precursor to Paul's other high-profile events that, along with actions by the NAWSA, culminated in the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U. S. Constitution in 1919 and its ratification in 1920.

[69][1]: 425–428 Paul's focus on a federal amendment contrasted sharply with the NAWSA's state-by-state approach to suffrage, leading to a rift between the Constitutional Committee and the national board.

It is also planned to honor many of the leaders of the suffrage movement, including Lucretia Mott, Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Alice Paul.

[77] In 1903, the NAWSA officially adopted a platform of states' rights that was intended to mollify and bring Southern U.S. suffrage groups into the fold.

The fiftieth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863 also fell in 1913, giving them even further incentive to march in the suffrage parade.

[83] But the Virginia-born Gardener tried to persuade Paul that including Black people would be a bad idea because the Southern delegations threatened to pull out of the march.

Paul had attempted to keep news about Black marchers out of the press, but when the Howard group announced they intended to participate, the public became aware of the conflict.