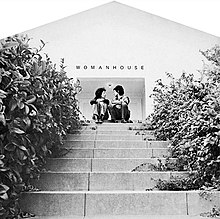

Womanhouse

Chicago, Schapiro, their students, and women artists from the local community, including Faith Wilding, participated.

[2] Together, the students and professors worked to build an environment where women's conventional social roles could be shown, exaggerated, and subverted.

[5] In 1971, the Feminist Art Program was slated to occupy a new building but found itself without adequate space at the start of the school year.

The lack of appropriate studio space paved the way for a collaborative group project set to highlight the ideological and symbolic conflation of women and houses.

[5] The goal of these discussions was for each woman to reach a higher level of self-perception, to validate their experiences, as well as the "search for subject matter" to incorporate into artwork and to address their individual aesthetic needs.

Chicago insisted her students feelings were the result of their own internalized sexism and unconscious manifestations of their difficulties dealing with female authority figures.

Many of the issues Chicago believed that the students needed to overcome were centered upon their lack of ability to perform traditionally masculine skills.

Chicago pushed students to become familiar using equipment such as various tools, to become comfortable in their ability to be assertive, and to view themselves as a part of the work force not defined by their domestic roles.

[9] It was thought that by teaching women to use power tools and proper building techniques, they would gain confidence and subsequently challenge the gendered expectations.

[12] Womanhouse began in an old deserted mansion on a residential street in Hollywood and became an environment in which: “The age-old female activity of homemaking was taken to fantasy proportions.

Members of the group knocked on doors to find the owner of the house, who one neighbor remarked would "certainly not be interested in the project."

Eventually a crew was needed to paint the exterior of the house, install locks and advise the women on basic electrical wiring.

I consider it a major formative experience in my development as an artist, teacher, and writer/editor.” Nancy Youdelman: "Looking back 25 years later, I have mixed feeling about the Feminist Art Program – We had something really incredible and unique and somehow we could not get beyond personalities and create a lasting support system."

Chicago and Schapiro invited other local artists Sherry Brody, Carol Edison Mitchell and Wanda Westcoast to participate and to hang their work alongside that of the other women.

Nonetheless, the ideas of all were influenced by the general aim of feminists in the late 1960s to revise women's position in society by bringing attention to their oppression, and this ideology clearly shared by the many individuals involved gave Womanhouse its impact.

[12] Working collaboratively on Womanhouse, the students gained new skills while developing a deeper understanding of human and personal experiences.

The students also provided tours of the exhibition, which gave them the opportunity to articulate their artwork while maintaining their personal vision when faced with criticism.

Even though the exhibition provided the students with great satisfaction and team effort some of the artists didn’t feel any personal accomplishment, and were looking forward to going back to work on their individual projects.

This allows the female to remove her bodily features when she is done with housework, implying that her physical body is inextricably linked to her societal role.

[1] Dining Room – by Beth Bachenheimer, Sherry Brody, Karen LeCocq, Robin Mitchell, Miriam Schapiro, Faith Wilding.

Lea, a character based on the aging courtesan from Colette's novel Chéri, sits in a watermelon pink bedroom.

According to Schapiro, The Dollhouse Room juxtaposes themes of "supposed safety and comfort in the home" with "terrors existing within its walls".

Womanhouse exhibition served as an introduction of feminism to the general public a revolutionary act for the early 1970s, and it sparked many debates.

[24] Though he remarks that "man's greatest creative acts may be but envious shadowings of her fecundity",[24] this review may have also highlighted stereotypical patriarchal attitudes surrounding connections between women's bodies, the domestic, and nature that Womanhouse attempted to critique.

Paula Harper argued that such language is an attempt by critics to soften the impact of Womanhouse by assimilating it according to conventions of femininity.

However, it is also argued that the piece illustrates, complicates and subverts a "false binary" of essential and constructed identity which enhances its value and relevancy.

In 1995, for example, the Bronx Museum of the Arts exhibited The Dollhouse by Sherry Brody and Miriam Schapiro, along with Faith Wilding's Womb Room, a recreation of Judy Chicago's Menstruation Bathroom, and Beth Bachenheimer's Shoe Closet, among others.”[23] The feminist spirit of Womanhouse lives on through the website Womenhouse, which was inspired by the groundbreaking 1972 exhibition.

Womenhouse catapults the issues raised by the original exhibition into the 21st century, within "a cyber-politics that addresses the multivalent vicissitudes of identity formation and domesticity.” Womanhouse was cited in 2019 by The New York Times as one of the 25 works of art that defined the contemporary age.

The project was produced by Johanna Demetrakas under the auspices of the American Film Society and is a part of Women Make Movies and was released in 1974.

[17] The film showed the installations, had the women artists speak about their work, and featured a consciousness raising session with Gloria Steinem.