Women in Italy

This includes family laws, the enactment of anti-discrimination measures, and reforms to the penal code (in particular with regard to crimes of violence against women).

Their status in Etruscan civilization differed from their Greek and the Roman peers, who were considered to be marginal and secondary in relation to men.

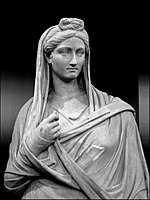

[9] Exceptional women who left an undeniable mark on history include Lucretia and Claudia Quinta, whose stories took on mythic significance; fierce Republican-era women such as Cornelia, mother of the Gracchi, and Fulvia, who commanded an army and issued coins bearing her image; women of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, most prominently Livia (58 BC-AD 29) and Agrippina the Younger (15 AD-59 AD), who contributed to the formation of Imperial mores; and the empress Helena (c.250–330 AD), a driving force in promoting Christianity.

[10] As is the case with male members of society, elite women and their politically significant deeds eclipse those of lower status in the historical record.

Some vivid snapshots of daily life are preserved in Latin literary genres such as comedy, satire, and poetry, particularly the poems of Catullus and Ovid, which offer glimpses of women in Roman dining rooms and boudoirs, at sporting and theatrical events, shopping, putting on makeup, practicing magic, worrying about pregnancy — all, however, through male eyes.

[11] The published letters of Cicero, for instance, reveal informally how the self-proclaimed great man interacted on the domestic front with his wife Terentia and daughter Tullia, as his speeches demonstrate through disparagement the various ways Roman women could enjoy a free-spirited sexual and social life.

Forbidden from marriage or sex for a period of thirty years, the Vestals devoted themselves to the study and correct observance of rituals which were deemed necessary for the security and survival of Rome but which could not be performed by the male colleges of priests.

Venetian-born Christine de Pizan wrote The City of Ladies in 1404, and in it she described women's gender as having no innate inferiority to men's, although being born to serve the other sex.

Powerful women rulers of the Italian Renaissance, such as Isabella d'Este, Catherine de' Medici, or Lucrezia Borgia, combined political skill with cultural interests and patronage.

Unlike her peers, Isabella di Morra (an important poet of the time) was kept a virtual prisoner in her own castle and her tragic life makes her a symbol of female oppression.

[15] By the late 16th and early 17th centuries, Italian women intellectuals were embraced by contemporary culture as learned daughters, wives, mothers, and equal partners in their household.

Outside the family setting, Italian women continued to find opportunities in the convent, and now increasingly also as singers in the theatre (Anna Renzi—described as the first diva in the history of opera—and Barbara Strozzi are two examples).

In the 18th-century, the Enlightenment offered for the first time to Italian women (such as Laura Bassi, Cristina Roccati, Anna Morandi Manzolini, and Maria Gaetana Agnesi) the possibility to engage in the fields of science and mathematics.

Italian sopranos and prime donne continued to be famous all around Europe, such as Vittoria Tesi, Caterina Gabrielli, Lucrezia Aguiari, and Faustina Bordoni.

In the early 19th century, some of the most influential salons where Italian patriots, revolutionaries, and intellectuals were meeting were run by women, such as Bianca Milesi Mojon, Clara Maffei, Cristina Trivulzio di Belgiojoso, and Antonietta De Pace.

In 1864, Anna Maria Mozzoni triggered a widespread women's movement in Italy, through the publication of Woman and her social relationships on the occasion of the revision of the Italian Civil Code (La donna e i suoi rapporti sociali in occasione della revisione del codice italiano).

[22] The most famous women of the time were actresses Eleonora Duse, Lyda Borelli, and Francesca Bertini; writers Matilde Serao, Sibilla Aleramo, Carolina Invernizio, and Grazia Deledda (who won the 1926 Nobel Prize in Literature); sopranos Luisa Tetrazzini and Lina Cavalieri; and educator Maria Montessori.

In 1927 the Jewish Women's Union Associzione delle Donne Ebree d'Italia (ADEI) was established[29] and committed itself to feminism, anti-fascism, as well as Zionism.

Any political activity by women was harshly repressed; in 1930 antifascist activist Camilla Ravera was sentenced to 15 years in prison.

[31] The only woman to whom some political prominence was given during the early Fascist period was Margherita Sarfatti; she was Benito Mussolini's biographer in 1925 as well as one of his mistresses.

It was not however until the 1970s that women in Italy scored some major achievements with the introduction of laws regulating divorce (1970), abortion (1978), and the approval in 1975 of the new family code.

Famous women of the period include politicians Nilde Iotti, Tina Anselmi, and Emma Bonino; actresses Anna Magnani, Sophia Loren, Monica Bellucci and Gina Lollobrigida; soprano Renata Tebaldi; ballet dancer Carla Fracci; costume designer Milena Canonero; sportwomen Sara Simeoni, Deborah Compagnoni, Valentina Vezzali, and Federica Pellegrini; writers Natalia Ginzburg, Elsa Morante, Alda Merini, and Oriana Fallaci; architect Gae Aulenti; scientist and 1986 Nobel Prize winner Rita Levi-Montalcini; astrophysicist Margherita Hack; astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti; pharmacologist Elena Cattaneo; and CERN Director-General Fabiola Gianotti.

Men make up the majority of the parliament but more than a third of the seats are held by women (around 36%, a higher rate than countries like Netherlands and Germany, as well as the average EU rate), which makes Italy the eighth country the EU by percentage of women in the national parliament.

Italian lawmakers are working to further protect and support women as they break gender stereotypes and join the workforce, but complete cultural change is slow.

The figure does not take into account some determining factors that characterize the labor market in Italy, such as the female employment rate, the different professional qualifications.

[69] Today, there is a growing acceptance of gender equality, and people (especially in the North[57]) tend to be far more liberal towards women getting jobs, going to university, and doing stereotypically male things.

However, in some parts of society, women are still stereotyped as being simply housewives and mothers, also reflected in the fact of a higher-than-EU average female unemployment.

[58] Ideas about the appropriate social behaviour of women have traditionally had a very strong impact on the state institutions, and it has long been held that a woman's 'honour' is more important than her well-being.

In 2000 female toplessness was officially legalized (in a nonsexual context) in all public beaches and swimming pools throughout Italy (unless otherwise specified by region, province or municipality by-laws) on 20 March 2000, when the Supreme Court of Cassation (through sentence No.

3557) determined that the exposure of the nude female breast, after several decades, was considered a "commonly accepted behavior", and therefore, "entered into the social costume".