Shale gas in the United States

[14] The article was criticized by, among others, The New York Times own public editor for lack of balance, in omitting facts and viewpoints favorable to shale gas production and economics.

[16][17][18] Also in 2011, Diane Rehm had Ian Urbina; Seamus McGraw, writer and author of "The End of Country"; Tony Ingraffea, a professor of engineering at Cornell; and John Hanger, former secretary of Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection; on a radio call-in show about Urbino's articles and the broader subject.

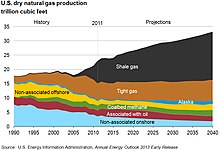

[19] In June 2011, when Urbina's article appeared in The New York Times , the latest figures for U.S. proved reserves of shale gas were 97.4 trillion cubic feet, as of the end of 2010.

[20] Over the next three years 2011 through 2013, shale gas production totaled 28.3 trillion cubic feet, about 29% of the end-of-2010 proved reserves.

The Big Sandy gas field, in naturally fractured Devonian shales, started development in 1915, in Floyd County, Kentucky.

Some policies have disincented market-based innovation, while Federal research and development expenditures have also advanced gas production techniques and supply alternatives.

[29] The Department of Energy partnered with private gas companies to complete the first successful air-drilled multi-fracture horizontal well in shale in 1986.

Microseismic imaging, an important input to both hydraulic fracturing in shale and offshore oil drilling, originated from coalbed research at Sandia National Laboratories.

The program applied two technologies that had been developed previously by industry, massive hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling, to shale gas formations.

In 1976, two engineers for the federally funded Morgantown Energy Research Center (MERC) patented an early technique for directional drilling in shale.

[32] The federal government also provided tax credits and rules benefiting the industry in the 1980 Energy Act.

"[36] Mitchell Energy began producing gas from the Barnett Shale of North Texas in 1981, but the results at first were uneconomic.

[43] The Antrim Shale of Upper Devonian age produces along a belt across the northern part of the Michigan Basin.

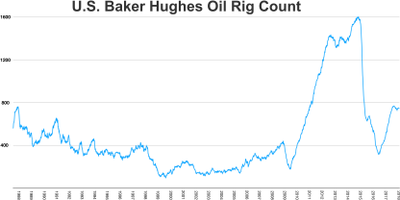

[45] Drilling expanded greatly in the past several years due to higher natural gas prices and use of horizontal wells to increase production.

[48] The Mississippian age Fayetteville Shale produces gas in the Arkansas part of the Arkoma Basin.

[49] The Floyd Shale of Mississippian age is a current gas exploration target in the Black Warrior Basin of northern Alabama and Mississippi.

[56] The Michigan public land auction took place in early May 2010 in one of "America's most promising oil and gas plays".

The New Albany has been a gas producer in this area for more than 100 years, but improved well completion technology has increased drilling activity.

[58] As of 2007, operators had completed approximately 50 wells in the Pearsall Shale in the Maverick Basin of south Texas.

[60] The upper Devonian shales of the Appalachian Basin, which are known by different names in different areas have produced gas since the early 20th century.

[72][73] Affordable domestic natural gas is essential to rejuvenating the chemical, manufacturing, and steel industries.

[75] The American Chemistry Council determined that a 25% increase in the supply of ethane (a liquid derived from shale gas) could add over 400,000 jobs across the economy, provide over $4.4 billion annually in federal, state, and local tax revenue, and spur $16.2 billion in capital investment by the chemical industry.

[76] They also note that the relatively low price of ethane would give United States manufacturers an essential advantage over many global competitors.

[79][80] A 2017 study finds that hydraulic fracturing contributed to job growth and higher wages: "new oil and gas extraction led to an increase in aggregate US employment of 725,000 and a 0.5 percent decrease in the unemployment rate during the Great Recession".

The price increase of the latter is most likely due to the royalty payments that property owners get from gas extracted under their land.

Manufacturers such as Dow Chemical are battling energy companies such as Exxon Mobil over whether the export of natural gas should be allowed.

[83] In 2016 and 2020, worldwide oversupply caused prices for natural gas to decrease below $2 per million British thermal units - $2.50 was the minimum for US producers to be cash flow positive in 2020.

"Support for conservative interests rises and Republican political candidates gain votes after booms, leading to a near doubling in the probability of a change in incumbency.

"[86] Complaints of uranium exposure and lack of water infrastructure emerged as environmental concerns for the rush.

[87][88] In Pennsylvania, controversy has surrounded the practice of releasing wastewater from "fracking" into rivers which serve as consumption reserves.