Workhouse

However, mass unemployment following the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, the introduction of new technology to replace agricultural workers in particular, and a series of bad harvests, meant that by the early 1830s the established system of poor relief was proving to be unsustainable.

The Statute of Cambridge 1388 was an attempt to address the labour shortage caused by the Black Death, a devastating pandemic that killed about one-third of England's population.

According to historian Derek Fraser, the fear of social disorder following the plague ultimately resulted in the state, and not a "personal Christian charity", becoming responsible for the support of the poor.

[12] So keen were some Poor Law authorities to cut costs wherever possible that cases were reported of husbands being forced to sell their wives, to avoid them becoming a financial burden on the parish.

In one such case in 1814 the wife and child of Henry Cook, who were living in Effingham workhouse, were sold at Croydon market for one shilling (5p); the parish paid for the cost of the journey and a "wedding dinner".

In his 1797 work, The State of the Poor, Sir Frederick Eden, wrote: The workhouse is an inconvenient building, with small windows, low rooms and dark staircases.

Coupled with developments in agriculture that meant less labour was needed on the land,[20] along with three successive bad harvests beginning in 1828 and the Swing Riots of 1830, reform was inevitable.

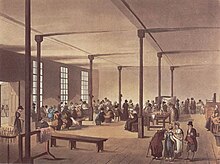

[29] They complained in particular that "in by far the greater number of cases, it is a large almshouse, in which the young are trained in idleness, ignorance, and vice; the able-bodied maintained in sluggish sensual indolence; the aged and more respectable exposed to all the misery that is incident to dwelling in such a society".

[35] Augustus Pugin compared Kempthorne's octagonal plan with the "antient poor hoyse", in what Felix Driver calls a "romantic, conservative critique" of the "degeneration of English moral and aesthetic values".

[47] Those refused entry risked being sentenced to two weeks of hard labour if they were found begging or sleeping in the open and prosecuted for an offence under the Vagrancy Act 1824.

[57] Many inmates were allocated tasks in the workhouse such as caring for the sick or teaching that were beyond their capabilities, but most were employed on "generally pointless" work,[58] such as breaking stones or removing the hemp from telegraph wires.

[58] Bone-crushing, useful in the creation of fertiliser, was a task most inmates could perform,[59] until a government inquiry into conditions in the Andover workhouse in 1845 found that starving paupers were reduced to fighting over the rotting bones they were supposed to be grinding, to suck out the marrow.

[42] Conditions were thereafter regulated by a list of rules contained in the 1847 Consolidated General Order, which included guidance on issues such as diet, staff duties, dress, education, discipline, and redress of grievances.

In 1869 Maria Rye and Annie Macpherson, "two spinster ladies of strong resolve", began taking groups of orphans and children from workhouses to Canada, most of whom were taken in by farming families in Ontario.

Although slow to take off, when workhouses discovered that the goods being produced were saleable and could make the enterprise self-financing, the scheme gradually spread across the country, and by 1897 there were more than 100 branches.

For instance, a breakfast of bread and gruel was followed by dinner, which might consist of cooked meats, pickled pork or bacon with vegetables, potatoes, yeast dumpling, soup and suet, or rice pudding.

[68] In an effort to force workhouses to offer at least a basic level of education, legislation was passed in 1845 requiring that all pauper apprentices should be able to read and sign their own indenture papers.

Religious services were generally held in the dining hall, as few early workhouses had a separate chapel but in some parts of the country, notably Cornwall and northern England,[75] there were more dissenters than members of the established church.

[75] A variety of legislation had been introduced during the 17th century to limit the civil rights of Catholics, beginning with the Popish Recusants Act 1605 in the wake of the failed Gunpowder Plot that year.

[84] A large workhouse such as Whitechapel, accommodating several thousand paupers, employed a staff of almost 200; the smallest may only have had a porter and perhaps an assistant nurse in addition to the master and matron.

[87] A second major wave of workhouse construction began in the mid-1860s, the result of a damning report by the Poor Law inspectors on the conditions found in infirmaries in London and the provinces.

[10] By the middle of the 19th century there was a growing realisation that the purpose of the workhouse was no longer solely or even chiefly to act as a deterrent to the able-bodied poor, and the first generation of buildings was widely considered to be inadequate.

About 150 new workhouses were built mainly in London, Lancashire and Yorkshire between 1840 and 1875, in architectural styles that began to adopt Italianate or Elizabethan features, to better fit into their surroundings and present a less intimidating face.

[88] By 1870 the architectural fashion had moved away from the corridor design in favour of a pavilion style based on the military hospitals built during and after the Crimean War, providing light and well-ventilated accommodation.

[89] As early as 1841 the Poor Law Commissioners were aware of an "insoluble dilemma" posed by the ideology behind the New Poor Law:[26] If the pauper is always promptly attended by a skilful and well qualified medical practitioner ... if the patient be furnished with all the cordials and stimulants which may promote his recovery: it cannot be denied that his condition in these respects is better than that of the needy and industrious ratepayer who has neither the money nor the influence to secure prompt and careful attendance.

[26] Hush-a-bye baby, on the tree top,When you grow old, your wages will stop,When you have spent the little you madeFirst to the Poorhouse and then to the grave By the late 1840s most workhouses outside London and the larger provincial towns housed only "the incapable, elderly and sick".

[92] The Royal Commission on the Poor Laws and Relief of Distress 1905–1909 reported that workhouses were unsuited to deal with the different categories of resident they had traditionally housed, and recommended that specialised institutions for each class of pauper should be established, in which they could be treated appropriately by properly trained staff.

[101] Camberwell workhouse (in Peckham, South London) continued until 1985 as a homeless shelter for more than 1,000 men, operated by the Department of Health and Social Security and renamed a resettlement centre.

[103] It is beyond the omnipotence of Parliament to meet the conflicting claims of justice to the community; severity to the idle and viscious and mercy to those stricken down into penury by the vicissitudes of God ...

[104] The Poor Law was not designed to address the issue of poverty, which was considered to be the inevitable lot for most people; rather it was concerned with pauperism, "the inability of an individual to support himself".