Wrangel Island

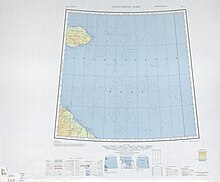

The International Date Line is therefore displaced eastwards at this latitude to keep the island, as well as the Chukchi Peninsula on the Russian mainland, on the same day as the rest of Russia.

In 1976, Wrangel Island and all of its surrounding waters were classified as a "zapovednik" (a "strict nature reserve") and, as such, receive the highest level of protection, excluding virtually all human activity other than conservation research and scientific purposes.

Captain Long, published in The Honolulu Advertiser, November 1867: I have named this northern land Wrangell Land as an appropriate tribute to the memory of a man who spent three consecutive years north of latitude 68°, and demonstrated the problem of this open polar sea forty-five years ago, although others of much later date have endeavored to claim the merit of this discovery.

Wrangel had noticed swarms of birds flying north, and, questioning the native population, determined that there must be an island undiscovered by Europeans existing in the Arctic Ocean.

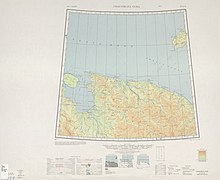

Wrangel Island consists of folded, faulted, and metamorphosed volcanic, intrusive, and sedimentary rocks ranging in age from Upper Precambrian to Lower Mesozoic.

Overlying the Precambrian strata are up to 2.25 km (7,400 ft) of Upper Silurian to Lower Carboniferous consisting of interbedded sandstone, siltstone, slate, argillite, some conglomerate and rare limestone and dolomite.

These strata are overlain by up to 2.15 km (7,100 ft) of Carboniferous to Permian limestone, often composed largely of crinoid plates, that is interbedded with slate, argillite and locally minor amounts of thick breccia, sandstone, and chert.

The uppermost stratum consists of 0.7 to 1.5 km (2,300 to 4,900 ft) of Triassic clayey quartzose turbidites interbedded with black slate and siltstone.

Late Neogene clay and gravel, which are only a few tens of meters thick, rest upon the eroded surface of the folded and faulted strata that compose Wrangel Island.

Species and genera present include various Arctic-adapted types of Androsace, Artemisia, Astragalus, Carex, Cerastium, Draba, Erigeron, Oxytropis, Papaver, Pedicularis, Potentilla, Primula, Ranunculus, Rhodiola, Rumex, Salix, Saxifraga, Silene and Valeriana, among others.

Several gull species are present, including glaucous, Ross', Sabine's and ivory gulls, long-tailed, pomarine and parasitic jaegers, and black-legged kittiwakes,[13] as well as many other sea and shorebird species, such as common and king eiders, horned puffins, pelagic cormorants, long-tailed ducks, red phalarope, dunlin, pectoral sandpipers, ruddy turnstones, red knots, black-bellied plovers, thick-billed murres and black guillemots.

The central and southern portions are warmer, with some of their valleys having semi-continental climates that support a number of sub-Arctic steppe-like meadow species.

These waters have among the lowest levels of salinity in the Arctic basin as well as a very high oxygen content and increased biogenic elements.

It also suggests large numbers of detrimental variants collecting in pre-extinction genomes, a warning for continued efforts to protect current endangered species with small population sizes.

[24] The earliest evidence of humans (and the only known pre-modern archaeological site on the island) is Chertov Ovrag on the southern coast, a Paleoeskimo short-term hunting camp which dates to around 3,600 years ago.

At the camp remains of birds (including the remains of at least 32 snow goose, six long-tailed duck, and one individual each of common murre and snow bunting), as well as two seals (including one bearded seal), a walrus and a polar bear were found in association with stone tools,[25] as well as a toggling harpoon head made of walrus tusk.

[27][28] Though the story may be mythical, the existence of an island or continent to the north was lent credence by the annual migration of reindeer across the ice, as well as the appearance of slate spear-points washed up on Arctic shores, made in a fashion unknown to the Chukchi.

Retired University of Alaska, Fairbanks, linguistics professor Michael E. Krauss has presented archaeological, historical, and linguistic evidence that Wrangel Island was a way station on a trade route linking the Inuit settlement at Point Hope, Alaska with the north Siberian coast, and that the coast was colonized in late prehistoric and early historic times by Inuit settlers from North America.

[32] George W. DeLong, commanding USS Jeannette, led an expedition in 1879 attempting to reach the North Pole, expecting to go by the "east side of Kellett land", which he thought extended far into the Arctic.

His ship became locked in the polar ice pack and drifted westward, passing within sight of Wrangel before being crushed and sunk in the vicinity of the New Siberian Islands.

In the same year on 23 August, the USS Rodgers, commanded by Lieutenant R. M. Berry during the second search for the Jeannette, landed a party on Wrangel Island which stayed about two weeks and conducted an extensive survey of the southern coast.

In 1914, members of the Canadian Arctic Expedition, organized by Vilhjalmur Stefansson, were marooned on Wrangel Island for nine months after their ship, Karluk, was crushed in the ice pack.

[36] The survivors were rescued by the American motorized fishing schooner King & Winge[37] after Captain Robert Bartlett walked across the Chukchi Sea to Siberia to summon help.

In 1921, Stefansson sent five settlers (the Canadian Allan Crawford, three Americans: Fred Maurer, Lorne Knight and Milton Galle, and Iñupiat seamstress and cook Ada Blackjack) to the island in a speculative attempt to claim it for Canada.

[41] In 1923, the sole survivor of the Wrangel Island expedition, Ada Blackjack, was rescued by a ship that left another party of 13 (American Charles Wells and 12 Inuit).

Wells subsequently died of pneumonia in Vladivostok during a diplomatic American-Soviet row about an American boundary marker on the Siberian coast, and so did an Inuk child.

They subsequently moved through Dalian, Kobe and Seattle (where another Inuk child drowned during the wait for the return trip to Alaska) back to Nome.

On 8 August a scout plane reported impassable ice in the strait, and Litke turned north, heading to Herald Island.

According to a 1936 article in Time magazine, Wrangel Island became the scene of a bizarre criminal story in the 1930s when it fell under the increasingly arbitrary rule of its appointed governor Konstantin Semenchuk.

He forbade the local Yupik Eskimos (recruited from Provideniya Bay in 1926)[46] to hunt walrus, which put them in danger of starvation, while collecting food for himself.