Wulfstan (died 1023)

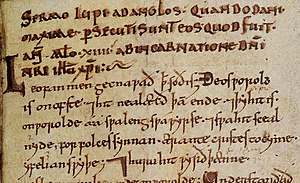

In 1014, as archbishop, he wrote his most famous work, a homily which he titled the Sermo Lupi ad Anglos, or the Sermon of the Wolf to the English.

Besides sermons Wulfstan was also instrumental in drafting law codes for both kings Æthelred the Unready and Cnut the Great of England.

But it is also likely that Wulfstan's position as archbishop of York, an important centre in the then politically sensitive northern regions of the English kingdom, made him not only a very influential man in the North, but also a powerful ally for the king and his family in the South.

It is indicative of Wulfstan's continuing political importance and savvy that he also acted as legal draftsman for, and perhaps advisor to, the Danish king Cnut, who took England's West Saxon throne in 1016.

With Ælfric of Eynsham, he is one of the two major vernacular writers in early eleventh-century England, a period which, ecclesiastically, was still very much enamoured of and greatly influenced by the Benedictine Reform.

Nothing less than the legitimacy of English Christendom rested on Englishmen's steadfastness on certain fundamental Christian beliefs and practices, like, for example, knowledge of Christ's life and passion, memorisation of the Pater Noster and the Apostles' Creed, proper baptism, and the correct date and method of celebrating Easter mass.

[21] In a series of homilies begun during his tenure as Bishop of London, Wulfstan attained a high degree of competence in rhetorical prose, working with a distinctive rhythmical system based around alliterative pairings.

He used intensifying words, distinctive vocabulary and compounds, rhetorical figures, and repeated phrases as literary devices.

These devices lend Wulfstan's homilies their tempo-driven, almost feverish, quality, allowing them to build toward multiple climaxes.

[22] This type of heavy-handed, though effective, rhetoric immediately made Wulfstan's homilies popular tools for use at the pulpit.

In this letter, an unknown contemporary refuses to do a bit of translation for Wulfstan because he fears he could never properly imitate the Bishop's style.

Wulfstan refused to include in his works confusing or philosophical concepts, speculation, or long narratives – devices which other homilies of the time regularly employed (likely to the dismay of the average parishioner).

Wulfstan's homilies are concerned only with the "bare bones, but these he invests with a sense of urgency of moral or legal rigorism in a time of great danger".

[f] He may also have been responsible, wholly or in part, for other extant anonymous Old English sermons, for his style can be detected in a range of homiletic texts which cannot be directly attributed to him.

This final block contains his most famous homily, the Sermo Lupi ad Anglos, where Wulfstan rails against the deplorable customs of his time, and sees recent Viking invasions as God's punishment of the English for their lax ways.

About 1008 (and again in a revision about 1016) he wrote a lengthy work which, although not strictly homiletic, summarises many of the favourite points he had hitherto expounded upon in his homilies.

As York was at the centre of a region of England that had for some time been colonised by people of Scandinavian descent, it is possible that Wulfstan was familiar with, or perhaps even bilingual in, Old Norse.

While in general he writes a variety of late West Saxon literary language, he uses in some texts words of Scandinavian origin, especially in speaking of the various social classes.

Under both Æthelred II and Cnut, Wulfstan was primarily responsible for the drafting of English law codes relating to both secular and ecclesiastical affairs, and seems to have held a prominent and influential position at court.

[33] Pushing for religious, social, political, and moral reforms, Wulfstan "wrote legislation to reassert the laws of earlier Anglo-Saxon kings and bring order to a country that had been unsettled by war and influx of Scandinavians.

[2] The historian Denis Bethell called him the "most important figure in the English Church in the reigns of Æthelred II and Cnut.

[42] The unique 11th-century manuscript of the Early English Apollonius of Tyre may only have survived because it was bound into a book together with Wulfstan's homilies.

In it he proclaims the depredations of the "Danes" (who were, at that point, primarily Norwegian invaders) a scourge from God to lash the English for their sins.

[8][44] Age of the Antichrist was a popular theme in Wulfstan's homilies, which also include the issues of death and Judgment Day.

[46] These six homilies also include: emphasis that the hour of the Antichrist is very near, warnings that the English should be aware of false Christs who will attempt to seduce men, warnings that God will pass judgement on man's faithfulness, discussion of man's sins, evils of the world, and encouragement to love God and do his will.

Wulfstan was also a book collector; he is responsible for amassing a large collection of texts pertaining to canon law, the liturgy, and episcopal functions.

A significant part of the Commonplace book consists of a work once known as the Excerptiones pseudo-Ecgberhti, though it has most recently been edited as Wulfstan's Canon Law Collection (a.k.a.

"Much Wulfstan material is, more-over, attributed largely or even solely on the basis of his highly idiosyncratic prose style, in which strings of syntactically independent two-stress phrases are linked by complex patterns of alliteration and other kinds of sound play.

[55] Similarly, "[o]ne early student of Wulfstan, Einenkel, and his latest editor, Jost, agree in thinking he wrote verse and not prose" (Continuations, 229).