Cabinet of curiosities

In addition to the most famous and best documented cabinets of rulers and aristocrats, members of the merchant class and early practitioners of science in Europe formed collections that were precursors to museums.

Evans goes on to explain that "no clear distinction existed between the two categories: all collecting was marked by curiosity, shading into credulity, and by some sort of universal underlying design".

It serves to authenticate its author's credibility as a source of natural history information, by showing his open bookcases (at the right), in which many volumes are stored lying down and stacked, in the medieval fashion, or with their spines upward, to protect the pages from dust.

[4] Above them, stuffed birds stand against panels inlaid with square polished stone samples, doubtless marbles and jaspers or fitted with pigeonhole compartments for specimens.

[5] When Albrecht Dürer visited the Netherlands in 1521, apart from artworks he sent back to Nuremberg various animal horns, a piece of coral, some large fish fins and a wooden weapon from the East Indies.

[6] The highly characteristic range of interests represented in Frans II Francken's painting of 1636 (illustration, above) shows paintings on the wall that range from landscapes, including a moonlit scene—a genre in itself—to a portrait and a religious picture (the Adoration of the Magi) intermixed with preserved tropical marine fish and a string of carved beads, most likely amber, which is both precious and a natural curiosity.

Sculptures both classical and secular (the sacrificing Libera, a Roman fertility goddess)[7] on the one hand and modern and religious (Christ at the Column[8]) are represented, while on the table are ranged, among the exotic shells (including some tropical ones and a shark's tooth): portrait miniatures, gem-stones mounted with pearls in a curious quatrefoil box, a set of sepia chiaroscuro woodcuts or drawings, and a small still-life painting[9] leaning against a flower-piece, coins and medals—presumably Greek and Roman—and Roman terracotta oil-lamps, a Chinese-style brass lock, curious flasks, and a blue-and-white Ming porcelain bowl.

The Kunstkammer of Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor (ruled 1576–1612), housed in the Hradschin at Prague, was unrivalled north of the Alps; it provided solace and retreat for contemplation[10] that also served to demonstrate his imperial magnificence and power in the symbolic arrangement of their display, ceremoniously presented to visiting diplomats and magnates.

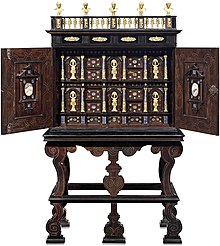

Similar collections on a smaller scale were the complex Kunstschränke produced in the early seventeenth century by the Augsburg merchant, diplomat and collector Philipp Hainhofer.

These were cabinets in the sense of pieces of furniture, made from all imaginable exotic and expensive materials and filled with contents and ornamental details intended to reflect the entire cosmos on a miniature scale.

In seventeenth-century parlance, both French and English, a cabinet came to signify a collection of works of art, which might still also include an assembly of objects of virtù or curiosities, such as a virtuoso would find intellectually stimulating.

In the second half of the eighteenth century, Belsazar Hacquet (c. 1735 – 1815) operated in Ljubljana, then the capital of Carniola, a natural history cabinet (German: Naturalienkabinet) that was appreciated throughout Europe and was visited by the highest nobility, including the Holy Roman Emperor, Joseph II, the Russian grand duke Paul and Pope Pius VI, as well as by famous naturalists, such as Francesco Griselini [it] and Franz Benedikt Hermann [de].

[14] A late example of the juxtaposition of natural materials with richly worked artifice is provided by the "Green Vaults" formed by Augustus the Strong in Dresden to display his chamber of wonders.

[15] Some strands of the early universal collections, the bizarre or freakish biological specimens, whether genuine or fake, and the more exotic historical objects, could find a home in commercial freak shows and sideshows.

In 1671, when visiting Thomas Browne (1605–1682), the courtier John Evelyn remarked, His whole house and garden is a paradise and Cabinet of rarities and that of the best collection, amongst Medails, books, Plants, natural things.

[16]Late in his life Browne parodied the rising trend of collecting curiosities in his tract Musaeum Clausum, an inventory of dubious, rumoured and non-existent books, pictures and objects.

He collected plants, bulbs, flowers, vines, berries, and fruit trees from Russia, the Levant, Algiers, France, Bermuda, the Caribbean, and the East Indies.

His son, John Tradescant the Younger (1608–1662) traveled to Virginia in 1637 and collected flowers, plants, shells, an Indian deerskin mantle believed to have belonged to Powhatan, father of Pocahontas.

Father and son, in addition to botanical specimens, collected zoological (e.g., the dodo from Mauritius, the upper jaw of a walrus, and armadillos), artificial curiosities (e.g., wampum belts, portraits, lathe turned ivory, weapons, costumes, Oriental footwear and carved alabaster panels) and rarities (e.g., a mermaid's hand, a dragon's egg, two feathers of a phoenix's tail, a piece of the True Cross, and a vial of blood that rained in the Isle of Wight).

Exhibitions of curiosities (as they were typically odd and foreign marvels) attracted a wide, more general audience, which "[rendered] them more suitable subjects of polite discourse at the Society.

In 1874 the museum acquired one hundred human skulls from Austrian anatomist and phrenologist, Joseph Hyrtl (1810–1894); a nineteenth-century corpse, dubbed the "soap lady"; the conjoined liver and death cast of Chang and Eng Bunker, the Siamese twins; and in 1893, Grover Cleveland's jaw tumor.

As Enlightenment thinkers placed growing emphasis on patterns and systems within nature, anomalies and rarities came to be regarded as potentially misleading objects of study.

[26] The Houston Museum of Natural Science houses a hands-on Cabinet of Curiosities, complete with taxidermied crocodile embedded in the ceiling a la Ferrante Imperato's Dell'Historia Naturale.

In Bristol, Rhode Island, Musée Patamécanique is presented as a hybrid between an automaton theater and a cabinet of curiosities and contains works representing the field of Patamechanics, an artistic practice and area of study chiefly inspired by Pataphysics.

In May 2008, the University of Leeds Fine Art BA programme hosted a show called "Wunder Kammer", the culmination of research and practice from students, which allowed viewers to encounter work from across all disciplines, ranging from intimate installation to thought-provoking video and highly skilled drawing, punctuated by live performances.

[30] In July 2021 a new Cabinet of Curiosities room was opened at The Whitaker Museum & Art Gallery in Rawtenstall, Lancashire, curated by artist Bob Frith,[31] founder of Horse and Bamboo Theatre.