Xhosa Wars

[citation needed] By the second half of the 18th century, European colonists gradually expanded eastward up the coast and encountered the Xhosa in the region of the Great Fish River.

The Dutch East India Company had demarcated the Great Fish River as the eastern boundary of the colony in 1779, though this was ignored by many settlers, leading to the First Cape Frontier War breaking out.

Discontented Khoikhoi then revolted, joined with the Xhosa in the Zuurveld, and started attacking, raiding farms occupied by European and Dutch settlers, reaching Oudtshoorn by July 1799.

British governor Sir Benjamin d'Urban believed that Hintsa ka Khawuta, King of the amaXhosa, commanded authority over all of the Xhosa tribes and therefore held him responsible for the initial attack on the Cape Colony, and for the looted cattle.

Originally assured of his personal safety during the treaty negotiations, Hintsa rapidly found himself held hostage and pressured with massive demands for cattle "restitution".

The British minister of colonies, Lord Glenelg, repudiated d'Urban's actions and accused the Boer retaliation against cattle raiders as being what instigated the conflict.

Governor Maitland imposed a new system of treaties on the chiefs without consulting them, while a severe drought forced desperate Xhosa to engage in cattle raids across the frontier in order to survive.

In addition, politician Robert Godlonton continued to use his newspaper the Graham's Town Journal to agitate for Eastern Cape settlers to annex and settle the land that had been returned to the Xhosa after the previous war.

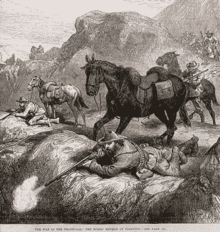

After inflicting a string of defeats on the Ngqika, Stockenström took a small and select group of his mounted commandos across the Colony's border and rapidly pushed into the independent Xhosa lands beyond the frontier.

[26] Paramount Chief Sarhili and his generals agreed to meet Stockenström (with his commandants Groepe, Molteno and Brownlee), unarmed, on a nearby mountain ridge.

However, British Imperial General Peregrine Maitland rejected the treaty and sent an insulting letter back to the Xhosa paramount-chief, demanding greater acts of submission and servility.

[19][28][better source needed] In the last month of the war (December 1847) Sir Harry Smith reached Cape Town as governor of the colony, and on the 23rd, at a meeting of the Xhosa chiefs, announced the annexation of the country between the Keiskamma and the Kei rivers to the British crown, thus reabsorbing the territory abandoned by order of Lord Glenelg.

Harry Smith also attacked and annexed the independent Orange Free State, hanging the Boer resistance leaders, and in the process alienating the Burghers of the Cape Colony.

Similarly, on 7 January, Hermanus and his supporters launched an offensive on the town of Fort Beaufort, which was defended by a small detachment of troops and local volunteers.

The Cape Government also eventually agreed to levy a force of local gunmen (predominantly Khoi) to hold the frontier, allowing Smith to free some imperial troops for offensive action.

With fresh men and supplies, the British expelled the remainder of Hermanus' rebel forces (now under the command of Willem Uithaalder) from Fort Armstrong and drove them west toward the Amatola Mountains.

Over the coming months, increasing numbers of Imperial troops arrived, reinforcing the heavily outnumbered British and allowing Smith to lead sweeps across the frontier country.

In February 1852, the British Government decided that Sir Harry Smith's inept rule had been responsible for much of the violence, and ordered him replaced by George Cathcart, who took charge in March.

She preached that the ancestors would return from the afterlife in huge numbers, drive all Europeans into the sea, and give the Xhosa bounteous gifts of horses, sheep, goats, dogs, fowls, and all manner of clothing and food in great amounts.

The Cape Colony addressed local needs through their own devices, creating a period of peace and prosperity, and achieved partial independence from Britain with "Responsible Government"; it had relatively little interest in territorial expansion.

High-pressure negotiations by Cape Prime Minister John Charles Molteno extracted a promise from Britain that imperial troops would stay put and on no account cross the frontier.

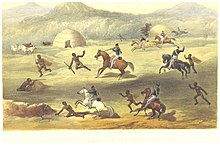

The Cape's local paramilitaries (mounted commandos of mainly Boer, Thembu and Fengu origin) were deployed by Molteno under the leadership of Commander Veldman Bikitsha and Chief Magistrate Charles Griffith.

[39] During the Cape's lightning quick campaign, Governor Frere had established a "war-council" at nearby King William's Town to direct the war against Gcalekaland.

The council was torn apart by argument from the beginning, as Frere refused Gcaleka appeals and worked towards full British occupation of Gcalekaland for white settlement and his future confederation.

It also considered the slow-moving British troop columns to be absurdly unsuitable for frontier warfare – immobile, ineffective and vastly more expensive than local Cape forces.

This last point of contention was chiefly exacerbated by Frere's insistence that the Cape's government pay for his imported British imperial troops, as well as its own local forces.

Militia deserted and protests erupted, in the face of which Cunynghame panicked and overreacted by unilaterally deploying the imperial troops to thinly encircle the whole of British Kaffraria.

He demanded the free command of the Cape's indigenous forces to operate and contain the violence, making it clear that he was content to sacrifice his job rather than tolerate further British interference.

Under this uninterrupted pressure the rebel forces quickly splintered and began to surrender, Sandile himself fled down into the valley of the Fish River where he was intercepted by a Fengu commando.

Had Bartle Frere not moved to the frontier and drawn the conflict into Britain's greater Confederation scheme, it would almost definitely have remained as only a brief patch of localised ethnic strife.