Yahya ibn Khalid

[4][5] This unique, and apparently accidental, relationship created strong bonds between them that proved crucial for the future fate of the Barmakids;[4] by Arab custom, ties of fosterage were equivalent to blood kinship.

[3] When al-Mahdi died suddenly while hunting in July 785, Yahya was instrumental in ensuring a smooth succession and avoiding a riot of the troops, who were likely to use the opportunity to extract several years' of payment from the exchequer.

Yahya and Queen al-Khayzuran kept the death secret, dismissed the troops with a gift of 200 dirhams, buried al-Mahdi, and sent for al-Hadi, who was then at Juzjan, to come to Baghdad and take over the throne.

Unlike al-Khayzuran, who did not hide her hostility to her older son, Yahya tried to mediate between the two brothers, urging Harun to a firmer defence of his rights, and al-Hadi to a more conciliatory stance.

With Harun safely ensconced on the throne, Yahya was named vizier, with plenipotentiary authority over all affairs of government, as well as a free hand in choosing personnel.

The Caliph gave strict orders to Yahya to seek al-Khayzuran's approval in all of his decisions, a regulation which reduced the status of the Vizier to a subordinate of the queen mother.

[16][17] Yahya made his two older sons, al-Fadl and Ja'far, his associates, sharing with them all duties and powers of his office, to the point that they also held the caliphal seal, and appear to also have been designated as viziers.

[19] As the representatives of the civil bureaucratic faction, the new Barmakid regime was characterized by the centralization of power in Baghdad: provincial governors lost in importance, especially as they were regularly changed after very brief tenures, in stark contrast to the long terms customary under al-Mansur.

[2] He commissioned the poet Aban al-Lahiqi to put the stories of Kalīla wa-Dimna, Mazdak, and Bilawhar wa-Būdhāsaf into verse; the latter especially was likely translated from Sanskrit for the Barmakids as well.

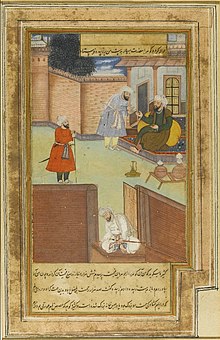

[2] In the anecdotes relayed by the chroniclers, Yahya also appears "as the host of numerous learned sessions and discussions among diverse participants" (van Bladel),[2] while Hugh Kennedy stresses that "the literary assemblies the Barmakids held were notable for the freedom with which unusual opin- ions were voiced".

Many of the stories about his life read more like exemplars written to show how a good minister and bureaucrat should behave and what he should accomplish , rather than as a historical record", the result of his idealization in the eyes of successive generations of Abbasid officials.