Isoroku Yamamoto

He commanded the fleet from 1939 until his death in 1943, overseeing the start of the Pacific War in 1941 and Japan's initial successes and defeats before his plane was shot down by U.S. fighter aircraft over New Guinea.

In April 1943, Yamamoto was killed after American code breakers intercepted his flight plans, enabling the United States Army Air Forces to shoot down his aircraft.

He also opposed war against the United States, partly because of his studies at Harvard University (1919–1921)[9] and his two postings as a naval attaché in Washington, D.C.,[10] where he learned to speak fluent English.

This was in spite of the fact that when Hideki Tojo was appointed prime minister on October 18, 1941, many political observers thought that Yamamoto's career was essentially over.

Two of the main reasons for Yamamoto's political survival were his immense popularity within the fleet, where he commanded the respect of his men and officers, and his close relations with the imperial family.

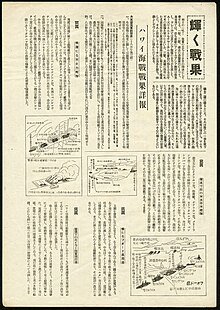

His daring plan for the Pearl Harbor attack had passed through the crucible of the Japanese naval establishment, and after many expressed misgivings, his fellow admirals had realized that Yamamoto spoke no more than the truth when he said that Japan's hope for victory in this [upcoming] war was limited by time and oil.

Nevertheless, Yamamoto accepted the reality of impending war and planned for a quick victory by destroying the United States Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor in a preventive strike, while simultaneously thrusting into the oil- and rubber-rich areas of Southeast Asia, especially the Dutch East Indies, Borneo, and Malaya.

For two decades, in keeping with the doctrine of Captain Alfred T. Mahan,[14] the Naval General Staff had planned in terms of Japanese light surface forces, submarines, and land-based air units whittling down the American fleet as it advanced across the Pacific until the Japanese Navy engaged it in a climactic Kantai Kessen ("decisive battle") in the northern Philippine Sea (between the Ryukyu Islands and the Marianas), with battleships fighting in traditional battle lines.

The attack was a success according to the parameters of the mission, which sought to sink at least four American battleships and prevent the United States from interfering in Japan's southward advance for at least six months.

The damaged aircraft were disproportionately dive and torpedo bombers, seriously reducing the ability to exploit the first two waves' success, so the commander of the First Air Fleet, Naval Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, withdrew.

Yamamoto later lamented Nagumo's failure to seize the initiative to seek out and destroy the American carriers or further bombard various strategically important facilities on Oahu, such as Pearl Harbor's oil tanks.

The First Air Fleet made a circuit of the Pacific, striking American, Australian, Dutch, and British installations from Wake Island to Australia to Ceylon in the Indian Ocean.

Along with the occupation of the Dutch East Indies came the fall of Singapore on February 15, and the eventual reduction of the remaining American-Filipino defensive positions in the Philippines on the Bataan peninsula on April 9 and Corregidor Island on May 6.

By late March, having achieved their initial aims with surprising speed and little loss, albeit against enemies ill-prepared to resist them, the Japanese paused to consider their next moves.

Yamamoto and a few Japanese military leaders and officials waited, hoping that the United States or Great Britain would negotiate an armistice or a peace treaty to end the war.

But when the British, as well as the Americans, expressed no interest in negotiating, Japanese thoughts turned to securing their newly seized territory and acquiring more with an eye to driving one or more of their enemies out of the war.

[22] Instead, the Imperial General Staff supported an army thrust into Burma in hopes of linking up with Indian nationalists revolting against British rule, and attacks in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands designed to imperil Australia's lines of communication with the United States.

Yamamoto argued for a decisive offensive strike in the east to finish off the American fleet, but the more conservative Naval General Staff officers were unwilling to risk it.

Although Tulagi and Guadalcanal were taken, the Port Moresby invasion fleet was compelled to turn back when Takagi clashed with an American carrier task force in the Battle of the Coral Sea in early May.

Just as importantly, Japanese operational mishaps and American fighters and anti-aircraft fire devastated the dive bomber and torpedo plane formations of both Shōkaku's and Zuikaku's air groups.

Following a nuisance raid by Japanese flying boats in May,[27] Nimitz dispatched a minesweeper to guard the intended refueling point for Operation K near French Frigate Shoals, causing the reconnaissance mission to be aborted and leaving Yamamoto ignorant of whether the Pacific Fleet carriers were still at Pearl Harbor.

Yamamoto committed Combined Fleet units to a series of small attrition actions across the south and central Pacific that stung the Americans, but in return suffered losses he could ill afford.

On April 14, 1943, the United States naval intelligence effort, codenamed "Magic", intercepted and decrypted a message containing specifics of Yamamoto's tour, including arrival and departure times and locations, as well as the number and types of aircraft that would transport and accompany him on the journey.

[31] Nimitz first consulted Admiral William Halsey Jr., Commander, South Pacific, and then authorized the mission on April 17 to intercept and shoot down Yamamoto's flight en route.

Yamamoto's body, along with the crash site, was found the next day in the jungle of the island of Bougainville by a Japanese search-and-rescue party, led by army engineer Lieutenant Tsuyoshi Hamasuna.

Some of his ashes were buried in the public Tama Cemetery, Tokyo (多摩霊園) and the remainder at his ancestral burial grounds at the temple of Chuko-ji in Nagaoka City.

Yamamoto was an avid gambler, enjoying Go,[37][page needed] shogi, billiards, bridge, mahjong, poker, and other games that tested his wits and sharpened his mind.

His memory from the original timeline intact, Yamamoto uses his knowledge of the future to help Japan become a stronger military power, eventually launching a coup d'état against Hideki Tōjō's government.

In the subsequent Pacific War, Japan's technologically advanced navy decisively defeats the United States, and grants all of the former European and American colonies in Asia full independence.

In the 2004 anime series Zipang, Yamamoto, voiced by Bunmei Tobayama, works to develop the uneasy partnership with the crew of the JMSDF Mirai, which has been transported back through time to 1942.