Japanese Antarctic Expedition

It was concurrent with two major Antarctic endeavours led respectively by Roald Amundsen and Robert Falcon Scott, and has been relatively overlooked in polar history.

Japan's slow emergence from isolation, following the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1868, kept it largely aloof from the growing international interest in polar exploration that escalated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

[14] Amid public indifference and press derision,[15] Shirase's fortunes turned when he secured the support of Count Okuma, the former prime minister, a figure of great prestige and influence.

[16] Okuma formed and presided over the Antarctic Expedition Supporters Association,[14] and the public began to contribute, mainly in small amounts from what Shirase described as the "student class".

[18] Hundreds applied to join the expedition, though none with any polar experience and only one, Terutaro Takeda, with any pretensions to a scientific background – he was an ex-schoolteacher who had also served as a professor's assistant.

[8] Dogs would be the prime mode of transport in the Antarctic; Shirase's initial preference for Manchurian ponies was impractical, since the expedition's ship, acquired with the assistance of Okuna, was too small to carry horses.

In his account to The Geographical Journal, Ivar Hamre describes a gala occasion, with flags and bunting flying,[23] while others write of brass bands, speeches and around 50,000 supporters present.

[22] After cargo trimming in Tateyama, the ship finally left Japan on 1 December,[24] carrying 27 men and 28 Siberian dogs,[8] leaving behind a debt that would increase considerably during the course of the expedition, and would burden Shirase for many years.

[25] In generally poor weather, Kainan Maru struggled southwards,[8][24] crossing the Equator on 29 December,[24] and arriving in Wellington, storm-battered and unannounced, on 7 February 1911.

[28] Many New Zealanders found it hard to accept that this was a genuine Antarctic expedition, given the lateness in the season, the inadequate-looking vessel, the unsuitable equipment and food, the apparent lack of charts.

[8][n 1] While some suspected them as being part of a Japanese plan to expand its influence southwards,[28] the New Zealand Times mocked the crew as "gorillas sailing about in a miserable whaler",[29] a remark that caused Shirase deep offence.

[8] By 17 February, in calmer weather, the crew captured its first penguin, an item of great curiosity: "It walked upright, looking for all the world like a gentleman in an overcoat".

[30] The small leaves turned to large disks, four metres across, through which Kainan Maru attempted to drive a passage: "The crunch and crack every time we smashed through a floe were not at all pleasant.

[38] Tension had grown following Japan's recent military victories in Russia and China, and as in New Zealand, there was considerable suspicion about the party's true purpose.

[40] However, Shirase and his party found support from a wealthy resident in the exclusive suburb of Vaucluse, who permitted them to set up a camp in a corner of his land at Parsley Bay.

[42] Nomura and another expedition member, Keiichi Tada, went back to Japan to report on the situation, and to seek further funding for a renewed attempt in the following season.

[45] A member of the expedition described the camp in idyllic terms: "surrounded by dense overgrown old trees... guava, bottlebrush, evergreen oak and pine...Standing on the rising ground behind the encampment you can gaze up at the hillside or turn to look at the sea below...like a landscape painting come alive".

[46] Shirase now revised his expedition's goals; Scott and Amundsen – of whom there was as yet no direct news – were, he reckoned, too far ahead of him for his aim of conquering the South Pole to be tenable.

[47] When the ship's refurbishment was complete and the expedition ready to depart, Shirase and his officers wrote to David thanking him for all the help he had given: "You were good enough to set the seal of your magnificent reputation upon our bona fides, and to treat us as brothers in the realm of science ... Whatever may be the fate of our enterprise, we will never forget you".

[44][49] On 19 November 1911 Kainan Maru sailed from the harbour, where in contrast to the mood at their arrival, they were seen off by throngs of well-wishers, "cheering and waving their white handkerchiefs and black hats in the air".

After celebrating New Year's Day in the traditional Japanese manner,[51] on 4 January 1912 the expedition reached Coulman Island, the turning point of the previous season.

[64] On 19 January, sea ice conditions having shifted, Kainan Maru was brought up close to the Barrier edge and the process of landing the shore party began.

[65] This proved difficult and dangerous, involving the cutting of an ice path through the steep cliffside to the Barrier summit to enable the transfer of men, dogs, provisions and equipment.

[69] Two would remain at a base camp to carry out meteorological observations, while a five-man Dash Patrol marched southward; these five men were Shirase, Takeda, Miisho and the two Ainu dog drivers.

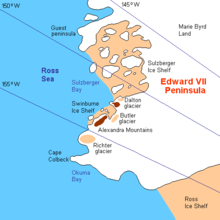

[77][n 3] After leaving Shirase's party, Kainan Maru sailed eastwards, arriving off the King Edward VII Land coast in Biscoe Bay on 23 January at 76°56'S, 155°55'W.

[79] The other party of three (Nishikawa, Watanabe and the cine-cameraman Taizumi), made better progress towards the Alexandra Mountains,[83][81] which Scott had observed from the sea in 1902, and named after the British queen.

Kainan Maru arrived at Wellington on 23 March, where Shirase and a small party left the ship to take a faster steamer home, so they could prepare for the expedition's return.

Kainan Maru was taken further east along the coast than any previous ship; the Dash Patrol sledged faster than anyone before, and became only the fourth team up to that time to travel beyond 80°S.

[20] The scientific data brought back by the expedition included important information on the geology of King Edward VII Land, and on ice and weather conditions in the Bay of Whales.

[97] In the wider world the expedition attracted little notice, eclipsed by the dramas surrounding Amundsen and Scott and also because the only available reports were in Japanese, a language little understood outside Japan.