Youth International Party

The Youth International Party (YIP), whose members were commonly called Yippies, was an American youth-oriented radical and countercultural revolutionary offshoot of the free speech and anti-war movements of the late 1960s.

[1][2] They employed theatrical gestures to mock the social status quo, such as advancing a pig called "Pigasus the Immortal" as a candidate for President of the United States in 1968.

[4][8] Other activists associated with the Yippies include Stew Albert, Judy Gumbo,[9] Ed Sanders,[10] Robin Morgan,[11] Phil Ochs, Robert M. Ockene, William Kunstler, Jonah Raskin, Wavy Gravy,[12][13] Steve Conliff, Jerome Washington,[14] John Sinclair, Jim Retherford,[15][16] Dana Beal,[17][18] Betty (Zaria) Andrew,[19][20] Joanee Freedom, Danny Boyle,[21] Ben Masel,[22][23] Tom Forcade,[24][25] Paul Watson,[26] David Peel,[27] Bill Weinberg,[28] Aron Kay,[29][30] Tuli Kupferberg,[31] Jill Johnston,[32] Daisy Deadhead,[33][34] Leatrice Urbanowicz,[35][36] Bob Fass,[37][38] Mayer Vishner,[39][40] Alice Torbush,[41][42] Patrick K. Kroupa, Judy Lampe,[43] Steve DeAngelo,[44] Dean Tuckerman,[41] Dennis Peron,[45] Jim Fouratt,[46] Steve Wessing,[23] John Penley,[47] Pete Wagner and Brenton Lengel.

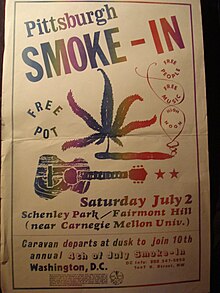

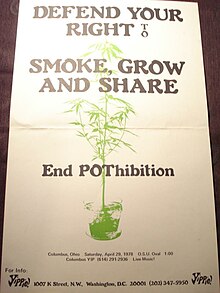

In the process of cross-fertilization at antiwar demonstrations, we had come to share an awareness that there was a linear connection between putting kids in prison for smoking pot in this country and burning them to death with napalm on the other side of the planet.

Even when praising a form of mass culture that had earned some grudging respect from the late-'60s left—rock 'n' roll—Rubin's list of musicians who "gave us the life/beat and set us free" included not just raucous originals like Jerry Lee Lewis and Bo Diddley but Fabian and Frankie Avalon, commercial confections that most lefty rock intellectuals disdained as insufficiently authentic.

[76][77][78] One cultural intervention that misfired was at Woodstock, with Abbie Hoffman interrupting a performance by The Who, trying to speak against the incarceration of John Sinclair, sentenced to 10 years in prison in 1969 after giving two joints to an undercover narcotics officer.

Abbie Hoffman and a group of future Yippies managed to get into a tour of the New York Stock Exchange, where they threw fistfuls of real and fake US$ from the balcony of the visitors' gallery down to the traders below, some of whom booed, while others began to scramble frantically to grab the money as fast as they could.

On the 40th anniversary of the NYSE event, CNN Money editor James Ledbetter described the now-famous incident: [The] group of pranksters began throwing handfuls of one-dollar bills over the railing, laughing the entire time.

The bills barely had time to land on the ground before guards began removing the group from the building, but news photos had been taken and the Stock Exchange "happening" quickly slid into iconic status.

[93] In his book A Trumpet to Arms: Alternative Media in America, author David Armstrong points out that the Yippie hybrid of performance art, Guerilla theater and political irreverence was often in direct conflict with the sensibility of the 60s American Left/peace movement: The Yippies' unorthodox approach to revolution, which emphasized spontaneity over structure, and media blitz over community organizing, put them almost as much at odds with the rest of the left as with mainstream culture.

The Yippies used media attention to make a mockery of the proceedings: Rubin came to one session dressed as an American Revolutionary War soldier, and passed out copies of the United States Declaration of Independence to people in attendance.

Hoffman quipped for the press, "I regret that I have but one shirt to give for my country", paraphrasing the last words of revolutionary patriot Nathan Hale; meanwhile Rubin, who was wearing a matching Viet Cong flag, shouted that the police were Communists for not arresting him also.

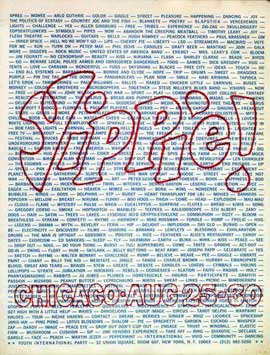

In response to the Festival of Life and other anti-war demonstrations during the Democratic convention, Chicago police repeatedly clashed with protesters, as many millions of viewers watched the extensive TV coverage of the events.

[105][106][107] In his book, American Fun: Four Centuries of Joyous Revolt, John Beckman writes: Never mind Hair, the so-called Chicago Eight (then Seven) trial was the countercultural performance of the sixties.

YIP had chapters all over the US and in other countries, with particularly active groups in New York City, Vancouver, Washington, D.C., Detroit, Milwaukee, Los Angeles, Tucson, Houston, Austin, Columbus, Dayton, Chicago, Berkeley, San Francisco and Madison.

[116] Vancouver Yippies invaded the US border town of Blaine, Washington, on May 9, 1970, to protest Richard Nixon's invasion of Cambodia and the shooting of students at Kent State.

[121] In 1972, Yippies and Zippies (a younger YIP radical breakaway faction whose "guiding spirit" was Tom Forcade)[122][123][124] staged protests at the Republican and Democratic Conventions in Miami Beach.

The demonstrators, members of the Youth International Party, or Yippies, completed the spree through downtown by jumping into the reflecting pool at City Hall in the sweltering Dallas heat.

[18][136] There was a culture clash when many of the hippie protesters strolled en masse into the nearby "Honor America Day" festivities with Billy Graham and Bob Hope.

Some were the editors of major underground newspapers or alternative magazines, including Yippies Abe Peck (Chicago Seed),[144] Jeff Shero Nightbyrd (New York's Rat and Austin Sun),[145] Paul Krassner (The Realist),[1][146] Robin Morgan (Ms. magazine),[147] Steve Conliff (Purple Berries, Sour Grapes[148] and Columbus Free Press),[149] Bob Mercer (The Georgia Straight and Yellow Journal),[150] Henry Weissborn (ULTRA),[151] James Retherford (The Rag), Mayer Vishner (LA Weekly),[39][152][153] Matthew Landy Steen and Stew Albert (Berkeley Barb and Berkeley Tribe),[154][155] Tom Forcade (Underground Press Syndicate and High Times)[156] and Gabrielle Schang (Alternative Media).

[159] The strange, legendary cult film Medicine Ball Caravan (partly financed by Tom Forcade),[160] chronicled Yippie drop-outs and a variety of other fascinating and dynamic characters of the era.

[167] The first-ever concert by the influential and iconic proto-punk band the New York Dolls, was a Yippie benefit to raise funds to pay legal fees for one of Dana Beal's marijuana arrests in the 1970s.

[175][176][177] Well-known bands on the tour included Michelle Shocked,[178] the Dead Kennedys,[179] the Crucifucks, MDC,[180] Cause for Alarm, Toxic Reasons and Static Disruptors.

[210] Perhaps one of the swan songs of Yippies was a groundbreaking effort to place a new voting option, None of the Above, on the election ballot in Santa Barbara County, in California, by the Isla Vista Municipal Advisory Council in 1976.

From the experimental combination of Isla Vista local politics, presidential campaigns and the Yippies, the name and spirit of this unexpected ballot initiative spread quickly—in the form of None of the Above music festivals, radio and television shows, rock bands, T-shirts, buttons, (decades later) countless websites and other related social phenomena.

[226] Some other books about that era: Woodstock Census: The Nationwide Survey of the Sixties Generation (Deanne Stillman and Rex Weiner),[227] The Panama Hat Trail (Tom Miller),[228][229]Can't Find My Way Home: America in the Great Stoned Age, 1945-2000 (Martin Torgoff),[230] Groove Tube: Sixties Television and the Youth Rebellion (Aniko Bodroghkozy),[231] and The Ballad of Ken and Emily: or, Tales from the Counterculture (Ken Wachsberger).

The editors (often doubling as authors) officially called themselves "The New Yippie Book Collective"; which included Steve Conliff (who wrote over half the volume), Dana Beal (head archivist), Grace Nichols, Daisy Deadhead, Ben Masel, Alice Torbush, Karen Wachsman, and Aron Kay.

[259] After official purchase, it was converted into the "Yippie Museum/Café and Gift Shop",[260][261] housing a multitude of counter-cultural and leftist memorabilia from all over the world, as well as providing an independently operated café that featured live music on scheduled nights.

[42] As of 2017, the old Yippie building at #9 Bleecker had been totally transformed into a successful Bowery-area Boxing club called "Overthrow", deliberately and artfully retaining much of its original Yippie/60s-revolutionary decor.

[271] In 2020, Netflix released the film The Trial of the Chicago 7, directed by Aaron Sorkin, which featured depictions of Yippie members Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin.