Yoga (philosophy)

[8][9] The metaphysics of Yoga is Samkhya's dualism,[web 1] in which the universe is conceptualized as composed of two realities: Puruṣa (witness-consciousness) and Prakṛti (nature).

The end of this bondage is called liberation, or mokṣa, by both the Yoga and Samkhya schools of Hinduism,[11] and can be attained by insight and self-restraint.

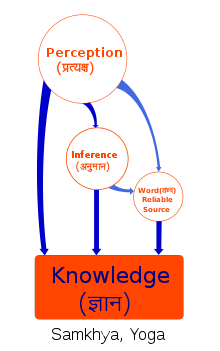

[web 1] The epistemology of Yoga-philosophy, like the Sāmkhya school, relies on three of six Pramanas as the means of gaining reliable knowledge.

[19] The root of the word "Yoga" is found in hymn 5.81.1 of the Rig Veda, a dedication to rising Sun-god in the morning (Savitri), interpreted as "yoke" or "yogically control".

[24] Only when Manas (mind) with thoughts and the five senses stand still, and when Buddhi (intellect, power to reason) does not waver, that they call the highest path.

The commentary by Vyasa may have been written by Patanjali himself, forming an integrated text called the Pātañjalayogaśāstra ("The Treatise on Yoga of Patañjali").

From the Samkhya school of Hinduism, the Yoga Sutras adopt the "reflective discernment" (adhyavasaya) of prakrti and purusa (dualism), its metaphysical rationalism, as well its three epistemic methods to gaining reliable knowledge.

[19] The third concept that the Yoga Sutras synthesize into its philosophy is the ancient ascetic traditions of isolation, meditation and introspection.

The Prakriti is the empirical, phenomenal reality which includes matter and also mind, sensory organs and the sense of identity (self, soul).

[31] The Samkhya-Yoga system espouses dualism between consciousness and matter by postulating two "irreducible, innate and independent realities: Purusha and Prakriti.

[36][37] In verse III.12, the Yogasutras state that this discerning principle then empowers one to perfect sant (tranquility) and udita (reason) in one's mind and spirit, through intentness.

[38] The benefits of Yoga philosophy of Hinduism are then summarized in verses III.46 to III.55 of Yogasutras, stating that the first five limbs leads to bodily perfections such as beauty, loveliness, strength and toughness; while the last three limbs through sanyama leads to mind and psychological perfections of perceptiveness, one's nature, mastery over egoism, discriminative knowledge of purity, self and soul.

Over sixty different ancient and medieval era texts of Yoga philosophy discuss Yamas and Niyamas.

[49][50] Other texts of the Yoga school of Hinduism include Kṣamā (क्षमा, forgiveness),[51] Dhṛti (धृति, fortitude, non-giving up in adversity), Dayā (दया, compassion),[51] Ārjava (आर्जव, non-hypocrisy)[52] and Mitāhāra (मितहार, measured diet).

[53] The Niyamas part of theory of values in the Yoga school include virtuous habits, behaviors and observances.

[63] Other texts of the Yoga school expanded the list of values under Niyamas, to include behaviors such as Āstika (आस्तिक, belief in personal God, faith in Self, conviction that there is knowledge in Vedas/Upanishads), Dāna (दान , charity, sharing with others),[64] Hrī (ह्री, remorse and acceptance of one's past/mistakes/ignorance, modesty)[65] Mati (मति, think and reflect, reconcile conflicting ideas)[66] and Vrata (व्रत, resolutions and vows, fast, pious observances).

[14] Unlike few other schools of Hinduism such as Advaita Vedanta, Yoga did not adopt the following three Pramanas: Upamāṇa (comparison and analogy), Arthāpatti (postulation, deriving from circumstances) or Anupalabdi (non-perception, negative/cognitive proof).

[15] Yoga philosophy allows the concept of God, unlike the closely related Samkhya school of Hinduism which is non-theistic.

[85] Patanjali defines Isvara (Sanskrit: ईश्वर) in verse 24 of Book 1, as "a special Self (पुरुषविशेष, puruṣa-viśeṣa)",[86] Sanskrit: क्लेश कर्म विपाकाशयैःपरामृष्टः पुरुषविशेष ईश्वरः ॥२४॥ – Yoga Sutras I.24This sutra adds the characteristics of Isvara as that special Self which is unaffected (अपरामृष्ट, aparamrsta) by one's obstacles/hardships (क्लेश, klesha), one's circumstances created by the past or by one's current actions (कर्म, karma), one's life fruits (विपाक, vipâka), and one's psychological dispositions or intentions (आशय, ashaya).

[87][88] The most studied ancient and medieval era texts of the Yoga school of philosophy include those by Patanjali, Bhaskara, Haribhadra (Jain scholar), Bhoja, and Hemachandra.

This is that Yoga.The Nyāya Sūtras by Akshapada variously dated to be from 4th to 2nd century BCE,[91] and belonging to the Nyaya school of Hinduism, in chapter 4.2 discusses the importance of Yoga as follows,[3] We are instructed to practice meditation in such places as a forest, a cave or a sand-bank.

For that purpose, there should be a purifying of our soul by abstinence from evil, and observance of certain virtues, as well as by following the spiritual injunctions gleaned from Yoga.

[99] The text synthesizes elements of Vedanta, Jainism, Yoga, Samkhya, Saiva Siddhanta and Mahayana Buddhism.