Yōkai

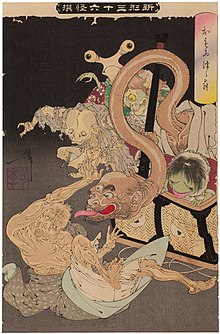

[This quote needs a citation] In the Edo period (1603 to 1868), many artists, such as Toriyama Sekien (1712-1788), invented new yōkai by taking inspiration from folk-tales or purely from their own imagination.

[5] According to Japanese ideas of animism, spirit-like entities were believed to reside in all things, including natural phenomena and objects.

[9] Chinkon rituals for ara-mitama that failed to achieve deification as benevolent spirits, whether through a lack of sufficient veneration or through losing worshippers and thus their divinity, became yōkai.

Elements of the tales and legends surrounding yōkai began to be depicted in public entertainment, beginning as early as the Middle Ages in Japan.

Literature such as the Kojiki, the Nihon Shoki, and various Fudoki expositioned on legends from the ancient past, and mentions of oni, orochi, among other kinds of mysterious phenomena can already be seen in them.

[20] Yasaburo was originally a bandit whose vengeful spirit (onryō) turned into a poisonous snake upon death and plagued the water in a paddy, but eventually became deified as the "wisdom god of the well".

[22][23] Medieval Japan was a time period where publications such as emakimono, Otogi-zōshi, and other visual depictions of yōkai started to appear.

Also, in 1908, Kyōka Izumi and Chikufū Tobari [ja] jointedly translated Gerhart Hauptmann's play The Sunken Bell.

Later works of Kyōka such as Yasha ga Ike [ja] were influenced by The Sunken Bell, and so it can be seen that folktales that come from the West became adapted into Japanese tales of yōkai.

The kamishibai from before the war, the manga industry, kashi-hon shops that continued to exist until around the 1970s, and television all contributed to the public knowledge and familiarity with yōkai.

For example, the classical yōkai represented by tsukumogami can only be felt as something realistic by living close to nature, such as with tanuki (Japanese raccoon dogs), foxes and weasels.

Furthermore, in the suburbs, and other regions, even when living in a primary-sector environment, there are tools that are no longer seen, such as the inkstone, the kama (a large cooking pot), or the tsurube (a bucket used for getting water from a well), and there exist yōkai that are reminiscent of old lifestyles such as the azukiarai and the dorotabō [ja].

As a result, even for those born in the first decade of the Shōwa period (1925–1935), except for some who were evacuated to the countryside, they would feel that those things that become yōkai are "not familiar" and "not very understandable".

From 1975 onwards, starting with the popularity of kuchisake-onna, these urban legends began to be referred to in mass media as "modern yōkai".

[29] This terminology was also used in recent publications dealing with urban legends,[30] and the researcher on yōkai, Bintarō Yamaguchi [ja], used this especially frequently.

[31] Furthermore, there is a favorable view that says that introducing various yōkai characters through these books nurtured creativity and emotional development of young readers of the time.

Shigeru Mizuki, the manga creator of such series as GeGeGe no Kitaro and Kappa no Sanpei, keeps yōkai in the popular imagination.

Other popular works focusing on yōkai include the Nurarihyon no Mago series, Yu Yu Hakusho, Inuyasha: A Feudal Fairy Tale, Yo-kai Watch and the 1960s Yokai Monsters film series, which was loosely remade in 2005 as Takashi Miike's The Great Yokai War and more recently Yukinobu Tatsu 's Dandadan.