Yukatchu

Ryukyuan Caste System: The Yukatchu class was also responsible for the development of and training methodology of their martial knowledge called Ti (Te).

[citation needed] The first time that the Yukatchu's weapons were confiscated was during the reign of King Shō Shin (1477–1526), who centralized the Ryukyu Kingdom by forcing the Aji to leave their respective Magiri and move to Shuri.

Toshihiro Oshiro, historian and Okinawan martial arts master, states: There is further documentation that in 1613 the Satsuma issued permits for the Ryukyu Samure to travel with their personal swords (tachi and wakizashi) to the smiths and polishers in Kagushima, Japan for maintenance and repair.

The former feudal Lord, his family and kin will be accorded princely treatment, and the persons of citizens, Ryūkyū Samure, their hereditary stipends, property and business interests will be dealt with in a manner as close to traditional customs as is possible.

To avoid armed revolt in Okinawa, as had happened in Japan, special ceremonies were performed for the Yukatchu class, where they were permitted to accept defeat honorably, and ritually cut off their hair (top-knot).

Peasants, who often had to perform manual labor for eighteen hours a day to pay taxes to the upper classes and sustain themselves, did not have the energy, time or financial resources to practice the warrior arts.

Shōshin Nagamine (recipient of the Fifth Class Order of the Rising Sun from the Emperor of Japan) states in his book The Essence of Okinawan Karate-Do, on pg.

An embassy was established in Fujian where yukatchu lived and studied; a small number would come and go every few years, so the individual residents at this trading post were constantly changing.

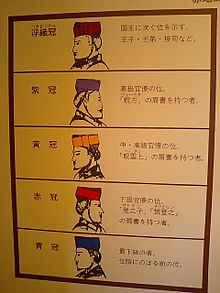

By 1700 or so, thirty years after the end of Shō Shōken's time, the yukatchu had developed truly into an aristocratic class, defining themselves by birth, by their rankings, wealth, and family name, more so than by their education or intellect.

He also issued regulations for the yukatchu in 1730, banning prostitution, which blossomed at the time and disrupted the noble nature of the aristocratic class, and setting mandates regarding the status of illegitimate offspring.

One group of Shuri yukatchu, led by Heshikiya Chōbin, spoke out against the strict, repressive Confucian system of ethics, advocating a more natural, Buddhistic attitude, and exclaiming the importance of love and equality among all people.

The number of yukatchu increased dramatically again at the end of the 18th century, as families who contributed to the support of the impoverished government were accorded noble status in exchange.

Perhaps one of the most damaging events for the stability and importance of the Kumemura yukatchu community was the establishment and gradual development of academies, and eventually a university, in Shuri.

When Ryukyu was formally annexed by Japan in 1879, Shigenori Uesugi,[4] the second appointed governor of the new territory, accused the yukatchu class as a whole of oppressing the Ryukyuan peasantry, and efforts were made to remove the nobles from power.

Similarly, Gregory Smits points out that while "noble" and "aristocrat" are commonly used to refer to yukatchu in English-language texts, these terms too have particular connotations based on their European origins which do not truly apply to the Ryukyuan case.