ZX81

[25] In July 1977 Radionics was rescued by a state agency, the National Enterprise Board (NEB), which recapitalised it, provided a loan facility and took effective control of the company by acquiring a 73% stake.

As he told the Sunday Times in April 1985, "We only got involved in computers in order to fund the rest of the business", specifically the development of the ultimately unsuccessful TV80 pocket television and C5 electric vehicle.

New Scientist stated in 1977 that "the price of an American kit in dollars rapidly translates into the same figure in pounds sterling by the time it has reached the shores of Britain".

[33] Off-the-shelf personal computers were also available for the high end of the market but were extremely expensive; Olivetti's offering cost £2,000, and the Commodore PET, launched in 1979, sold for £700.

It had no screen but instead used an LED segment display (though Science of Cambridge did produce an add-on module allowing it to be hooked up to a UHF TV); it had no case, consisting of an exposed circuit board; it had no built-in storage capabilities and only 256 bytes of memory; and input was via a 20-key hexadecimal keyboard.

[34] Its distinctive wedge-shaped white case concealing the circuitry and the touch-sensitive membrane keyboard were the brainchild of Rick Dickinson, a young British industrial designer who had recently been hired by Sinclair.

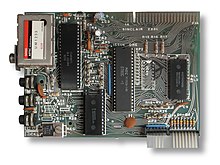

The main difference between the two machines lay in the internal software; when the ZX81 was released, ZX80 owners were able to upgrade by the relatively simple expedient of plugging a new ROM onto the circuit board.

Sinclair responded by launching his own half-price deal, offering schools the chance to buy a ZX81 and 16 KB RAM pack for £60, plus a ZX Printer at half price, for a total cost of £90.

This short-lived technology of the day was cheaper and quicker than the design of a customised logic chip, which typically required very high volumes to recoup its development cost.

[65] Unfortunately for Vickers, he introduced a briefly notorious error – the so-called "square-root bug" that caused the square root of 0.25 to be returned erroneously as 1.3591409 – as a result of problems with integrating the ZX Printer code into the ROM.

"[46] The company's slowness in replacing returns and delivering freshly ordered machines meant that Sinclair Research gained a reputation for poor customer service.

"[54] A New Scientist retrospective published in 1986 commented: Sir Clive's marketing achievement was to downgrade the "concept" of a computer to the point where he could claim to provide one for less than the magical £100 mark.

In the main, it was ignorance of genuine computer technology that fired the success of the ZX range, despite the availability of accessories that, albeit inefficiently, turned the Z80 processor chip at the heart of these up-market toys into the core of a useful machine.

A big splash on launch produced a large influx of cash at the outset of a campaign, though it did also depend on the advertiser having enough product to satisfy the initial surge in demand.

His "Uncle Clive" persona is said to have been created by the gossip columnist for Personal Computer World,[80] while the media praised Sinclair as a visionary genius (or even, in the words of The Sun, "the most prodigious inventor since Leonardo.")

As Ian Adamson and Richard Kennedy put it, Sinclair outgrew "the role of microcomputer manufacturer and accepted the mantle of pioneering boffin leading Britain into a technological utopia.

The advantage of his approach is that vacillating customers are drawn into the fold while the product's promotion retains a commercial urgency, and the costings of the competition are thrown into utter disarray.

The "Computer Know-How" sections were swamped with eager customers, overwhelming the 300 staff who had been trained to demonstrate the machines; a Financial Times correspondent wrote of being "dazed and bewildered by the crowds of schoolchildren clustered round the ZX81 in your local branch of W.H.

[97] Sinclair launched the ZX81 in the United States in November 1981 at a price of $149.95 assembled and $99.95 in kit form, initially selling directly to the American market by mail order.

The Japanese market's favourable reaction to the ZX81 led Mitsui to begin selling the ZX81 over the counter in large bookshops from September 1982, with annual sales of 20,000 units predicted.

[104] There was no such restriction on sales to communist China and in November 1983 Sinclair Research announced that it had signed an agreement to export ZX81 kits to a factory in Guangzhou, where they would be assembled for the Chinese market.

He highlighted weaknesses in the manual and Sinclair's accompanying software, criticising them for "a misconceived design and sloppiness in execution which make the machine seem harder to use and more limited than it should" and questioned whether it might be more worthwhile to save up for a more powerful computer such as Acorn or Commodore's offerings.

[90] Billy Garrett of Byte, who already owned a ZX80, complimented the Timex/Sinclair 1000's manual (although he regretted the removal of the British original's humour), the "state-of-the-art circuitry", and the BASIC for being "remarkably powerful" despite the small ROM size.

Clive Sinclair was "amused and gratified" by the attention the machine received[30] but other than what Clarke described as "a few remarkably poor programs on cassette",[78] his company made little effort to exploit the demand, effectively ceding a very lucrative market to third party suppliers, a decision that undoubtedly forfeited a lot of potential earnings.

Smith, for instance, was able to exploit a peculiarity of the ZX81; owners found that technically obsolete low-fidelity mono tape cassette recorders worked better as storage devices than higher-quality music systems.

These included RAM packs providing up to 64 KB of extra memory and promising to "fit snugly ... giving a firm connection" to the computer,[114] typewriter-style keyboards, more advanced printers and sound generators.

The TS1000 was launched in July 1982 and sparked a massive surge of interest; at one point, the Timex phoneline was receiving over 5,000 calls an hour, 50,000 a week, inquiring about the machine or about microcomputers in general.

[127] Competitors such as Apple, Atari, Commodore and Texas Instruments promoted their machines as being for business or entertainment rather than education, highlighting the value of computers with ready-made applications and more advanced features such as graphics, colour and sound.

[130] Some companies outside the US and UK produced their own "pirate" versions of the ZX81 and Timex Sinclair computers,[131] aided by weak intellectual property laws in their countries of origin.

[46] Ian Adamson and Richard Kennedy note that the popularity of the ZX81 was "subtly different from the run-of-the-mill social fad"; although most enthusiasts were in their teens or early twenties, many were older users – often parents who had become fascinated by the ZX81s that they had bought for their children.