Carnegie Hall

It also faces the Rodin Studios and 888 Seventh Avenue to the west; Alwyn Court, The Briarcliffe, the Louis H. Chalif Normal School of Dancing, and One57 to the north; the Park Central Hotel to the southwest; and CitySpire and New York City Center to the southeast.

[8][9][10] The area contains several buildings constructed as residences for artists and musicians, such as 130 and 140 West 57th Street, the Osborne, and the Rodin Studios.

[11] By the 21st century, the artistic hub had largely been replaced with Billionaires' Row, a series of luxury skyscrapers around the southern end of Central Park.

[13][15] Carnegie Hall was constructed with heavy masonry bearing walls, as lighter structural steel framework was not widely used when the building was completed.

[17][18] As originally designed, the terracotta and brick were both brown, and the pitched roof was made of corrugated black tile,[18] but this was later replaced with the eighth floor.

[20] The lobby ceiling was designed as a barrel vault, containing soffits with heavy coffers and cross-arches, and was painted white with gold decorations.

[34][35] The rebuilt lobby contains geometric decorations evocative by the work of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, as well as Corinthian-style capitals with lighting fixtures.

In its place, a temporary framework of steel pipe columns, supporting I-beam girders and thick Neoprene insulation pads, was installed.

[51] An elliptical concrete wall, measuring 12 inches (300 mm) wide, surrounds Zankel Hall and supports the Stern Auditorium.

A proscenium arch made of plywood, as well as a paneled wall behind the stage, were installed after the recital hall's completion but were removed in the 1980s to improve acoustics.

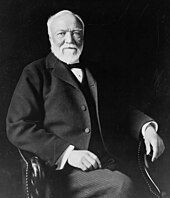

[13][68][71] While studying music in Germany in 1887, the younger Damrosch was introduced to the businessman Andrew Carnegie, who served on the board of not only the Oratorio Society but also the New York Symphony.

[72][73] In early March 1889, Morris Reno, director of the Oratorio and New York Symphony societies acquired nine lots on and around the southeast corner of Seventh Avenue and 57th Street.

[14] The Henry Elias Brewery owned the corner of Seventh Avenue and 56th Street and originally would not sell the land, as its proprietor believed the site had a good water source.

[90] The Music Hall officially opened on May 5, 1891, with a rendition of the Old 100th hymn, a speech by Episcopal bishop Henry C. Potter, and a concert conducted by Walter Damrosch and Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

[102] Carnegie Hall officials renovated the building in 1920, replacing its porte-cochère, overhauling the Philharmonic Society's office, and removing staircases for about $70,000.

[103] By late 1924, the Carnegie Foundation was considering selling the hall to a private developer because of increasing financial deficits, which amounted to $15,000 a year.

[43][50] Simon sold the entire stock of Carnegie Hall, Inc., the venue's legal owner, to a commercial developer, the Glickman Corporation, in July 1956 for $5 million.

[122] The move gained support from mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr., who created a taskforce to save Carnegie Hall in early 1960,[132][133] but Simon and his co-owners still filed eviction notices against some studio tenants.

By the mid-1970s, the venue suffered from burst pipes and falling sections of the ceiling, and there were large holes in the balconies that patrons could put their feet through.

[136] The next year, the Carnegie Hall Corporation and the New York City government signed a memorandum of understanding, which would permit the development of the adjacent site to the east, a parking lot.

[36][136] A controversy also emerged when the Carnegie Hall Corporation started evicting longtime tenants of the upper-story studios, particularly those who refused to pay steeply increased rents.

[157][158][159] As part of the third phase of renovations, a recording studio called the Alice and Jacob M. Kaplan Space was built within the old chapter room on the fifth floor, directly above the main hall.

[56] The main hall (including the Stern Auditorium) was reopened on December 15, 1986, with a gala featuring Zubin Mehta, Frank Sinatra, Vladimir Horowitz, and the New York Philharmonic.

[191] In June 2003, tentative plans were made for the Philharmonic to return to Carnegie Hall beginning in 2006, and for the orchestra to merge its business operations with those of the venue.

[45][193] Music critic Anthony Tommasini praised Zankel Hall's flexibility, though he said "the builders did not quite succeed in insulating the auditorium from the sounds of passing trains".

[194] Architecturally, the space was described by critic Herbert Muschamp as "a luxury version of a black-box theater, the hall has the feel of a broadcasting studio, which it partly is".

[31] By the 1900s, conductors such as Richard Strauss, Ruggero Leoncavallo, Camille Saint-Saëns, Alexander Scriabin, Edward Elgar, and Sergei Rachmaninoff were staging or performing their own music at Carnegie Hall.

[213] On November 14, 1943, the 25-year-old Leonard Bernstein had his major conducting debut when he had to substitute for a suddenly ill Bruno Walter in a concert that was broadcast by CBS.

[234] Promoter Sid Bernstein convinced Carnegie officials that allowing a Beatles concert at the venue "would further international understanding" between the United States and Great Britain.

[260] Alternatives to violinist Jascha Heifetz as the second party include an unnamed beatnik, bopper, or "absent-minded maestro", as well as pianist Arthur Rubinstein and trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie.