Zapatista Army of National Liberation

The group takes its name from Emiliano Zapata, the agrarian revolutionary and commander of the Liberation Army of the South during the Mexican Revolution, and sees itself as his ideological heir.

The situation led many young people to consider the legal channels of political participation closed and to bet on the formation of clandestine armed organizations to seek the overthrow of a regime that from their point of view was authoritarian, and thus improve the living conditions of the population.

According to Mario Arturo Acosta Chaparro, in his report Subversive movements in Mexico, "they had established their areas of operations in the states of Veracruz, Puebla, Tabasco, Nuevo León and Chiapas."

In February 1974, a confrontation took place in San Miguel Nepantla [Wikidata], State of Mexico, between a unit of the Mexican Army, under the command of Mario Arturo Acosta Chaparro, and members of the FLN, some of whom died during combat, reportedly having been tortured.

[18][19] Over the years, the group slowly grew, building on social relations among the indigenous base and making use of an organizational infrastructure created by peasant organizations and the Catholic Church (see Liberation theology).

[20] In the 1970s, through the efforts of the Roman Catholic Diocese of San Cristóbal de Las Casas, most indigenous communities in the Lacandon forest were already politically active and had practice in dealing with governmental agencies and local officials.

[23] The EZLN also called for greater democratization of the Mexican government, which had been controlled by the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (Institutional Revolutionary Party, also known as PRI) for 65 years, and for land reform mandated by the 1917 Constitution of Mexico, which had been repealed in 1991.

"[27] Following a ceasefire on January 12, peace talks commenced later in the month between Catholic bishop Samuel Ruiz for the Zapatistas and former mayor of Mexico City, Manuel Camacho Solis, for the state.

[29] Arrest-warrants were made for Marcos, Javier Elorriaga Berdegue, Silvia Fernández Hernández, Jorge Santiago, Fernando Yanez, German Vicente and other Zapatistas.

Javier Elorriaga was captured on February 9, 1995, by forces from a military garrison at Gabina Velázquez in the town of Las Margaritas, and was later taken to the Cerro Hueco prison in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas.

In April 2000, Vicente Fox, the presidential candidate for the opposition National Action Party (PAN), sent a new proposal for dialogue to Subcomandante Marcos, without obtaining a response.

This declaration reiterated the support for the indigenous peoples, who make up roughly one-third of the population of Chiapas, and extended the cause to include "all the exploited and dispossessed of Mexico".

The following days were marked by violence, with some 216 arrests, over 30 rape and sexual abuse accusations against the police, five deportations, and one casualty, a 14-year-old boy named Javier Cortes shot by a policeman.

A 20-year-old UNAM economics student, Alexis Benhumea, died on the morning of June 7, 2006, after being in a coma caused by a blow to the head from a tear-gas grenade launched by police.

[43] In mid-January 2009, Marcos made a speech on behalf of the Zapatistas in which he supported the resistance of the Palestinians as "the Israeli government's heavily trained and armed military continues its march of death and destruction".

"[44] On December 21, 2012, tens of thousands of EZLN supporters marched silently through five cities in the state of Chiapas: Ocosingo, Las Margaritas, Palenque, Altamirano and San Cristóbal.

The poet and journalist Hermann Bellinghausen, specialist in coverage of the movement, ended his chronicle in this way:[48] Able to "appear" suddenly, the rebellious indigenous "disappeared" as neatly and silently as they had arrived in this city at dawn that, two decades after the EZLN's traumatic uprising here on the new year of 1994, received them with care and curiosity, without any expression of rejection.

Under the arches of the mayor's office, which today suspended its activities, dozens of Ocosinguenses gathered to photograph with cell phones and cameras the spectacular concentration of hooded people who filled the park like a game of Tetris, advancing between the planters with an order that seemed choreographed, to get the platform installed quickly from early on, raise their fist and say, quietly, "here we are, once again".

In May 2017, María de Jesús Patricio Martínez, a woman of Mexican and Nahua heritage, was selected to stand,[52][53] but she was unable to gather the 866,000 signatures required to appear on the ballot.

The ideology of the Zapatista movement, Neozapatismo, synthesizes Mayan tradition with elements of libertarian socialism,[63] anarchism,[9] Catholic liberation theology[64] and Marxism.

The EZLN opposes economic globalization, arguing that it severely and negatively affects the peasant life of its indigenous support base and oppresses people worldwide.

[69] The Zapatistas have used organizations like the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) to raise awareness for their rebellion and indigenous rights, and what they claim is the Mexican government's lack of respect for the country's impoverished and marginalized populations.

Indigenous catechists that taught liberation theology proved essential in organising the local population, and gave the aura of legitimacy to movements hitherto considered too dangerous or radical.

[74] In the decades preceding the 1994 uprising, the Roman Catholic Diocese of San Cristóbal de Las Casas, guided by the Bishop Samuel Ruiz Garcia, developed a cadre of indigenous catechists.

[64] In practice, these liberationist Christian catechists promoted political awareness, established organizational structures, and helped raise progressive sentiment among indigenous communities in Chiapas.

[76] Anthropologists Duncan Earle and Jeanne Simonelli assert that the liberationist Catholicism spread by the aforementioned catechists which emphasized helping the poor and addressing material conditions in tandem with spiritual ones brought many indigenous Catholics into the Zapatista Movement.

[83] The Zapatistas initially focused on the news media as a weak point of the Mexican federal government and turned the Chiapas war from a military impossibility to an informational guerrilla movement.

[84] Marcos and the Zapatistas would issue hundreds of missives, hold encuentros (mass meetings), give numerous interviews, meet high-profile public and literary figures including Oliver Stone, Naomi Klein, Gael García Bernal, Danielle Mitterrand, Régis Debray, John Berger, Eduardo Galeano, Gabriel García Márquez, José Saramago and Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, participate in symposia and colloquia, deliver speeches, host visits by thousands of national and international activists, and participate in two marches that toured much of the country.

By employing mythopoetics—a style characterized by metaphorical narratives, allegories, and cultural symbolism—they effectively communicated Mesoamerican philosophical tenets while broadening their appeal to both local and international audiences.

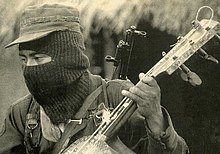

[92] Subcomandante Marcos's image and signature balaclava and pipe are widely appropriated in the tourism industry, similar to the iconic status of Che Guevara.

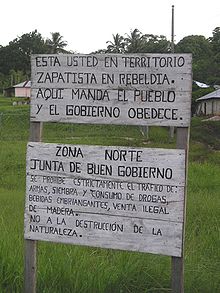

The top sign reads, in Spanish, "You are in Zapatista rebel territory. Here the people command and the government obeys."

Bottom sign: "North Zone. Council of Good Government. Trafficking in weapons, planting of drugs, drug use, alcoholic beverages, and illegal selling of wood are strictly prohibited. No to the destruction of nature."

Zapata lives, the fight continues...

You are in Zapatista territory in Rebellion. Here the people rule, the government obeys.