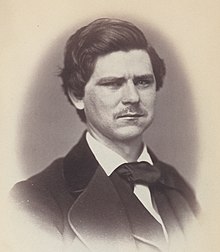

Zebulon Vance

[13][12][14] His paternal grandfather, David Vance, was a member of the North Carolina House of Commons and a colonel in the American Revolutionary War, serving under George Washington at Valley Forge.

[18][12] Vance then went to Raleigh, where he studied law with Judge William Horn Battle of the North Carolina Supreme Court and Samuel F. Phillips, former Solicitor General of the United States.

[4] The opposition paper, the Asheville News wrote, "Mr. Vance is the Spectator's specialty, and at every mention of his name it sputters and snaps and snarls like a cat with its tail in a steel trap.

[24] Instead, he wrote a letter that was published in the Fayetteville Observer saying, "If, therefore, my fellow citizens believe that I could serve the great Cause better as Governor than I am now doing, and should see proper to confer this responsibility upon me without solicitation on my part, I should not feel at liberty to decline it, however conscious of my own unworthiness.

[24] It also helped that Johnston's Democratic party could be blamed for "high prices, conscription, military defeats, suffering of the soldiers, and the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus".

[24] Despite Vance's continued requests to Richmond for military reinforcements, he was ignored and North Carolina's defenses failed when 10,000 Union troops advanced on Kinston in December 1862.

[13] When President Jefferson Davis announced plans to indefinitely imprison Southerners suspected of "disloyalty" without a trial, Vance refused to deprive North Carolinians of their constitutional rights, saying he would rather recall the state's soldiers fighting in Virginia and order them to protect his constituents by force if necessary.

[31][32] Davis did not risk challenging Vance; as a result, North Carolina was the only state to observe the right of habeas corpus and keep its courts fully functional during the war.

[35]On April 26, 1865, Vance learned that Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston had surrendered his forces to Sherman at the James Bennett farmhouse near Durham, North Carolina.

[13] On April 28, Vance gave a final proclamation to the people of his state, telling both civilians and soldiers "to retire quietly in their homes, and exert themselves in preserving order".

[12] Then, wiping his eyes, Vance expressed concern for his wife and children who had no money to live on and worried about the "indignities" that North Carolina might suffer in the aftermath of the war.

[47] In 1870, the North Carolina legislature appointed Vance to the United States Senate, but because of the Fourteenth Amendment, he was not eligible to serve unless authorized by a two-thirds majority vote in both houses of Congress.

[48] Historian Leonard Rogoff, president of Jewish Heritage North Carolina, also notes that Vance established a relationship with Samuel Wittkowsky, a Jew and fellow Mason.

In short, I regard it as an unmistakable policy to imbue these black people with a hearty North Carolina feeling and make them cease to look abroad for the aids to their progress and civilization, and the protection of their rights as they have been taught to do, and teach them to look to their State instead...."[12] Two years later, his message to the legislature announced that the Board of Education had created two normal schools—a summer institute at the University of North Carolina for white teachers and a new permanent institution, the State Colored Normal School, for black teachers at the Howard School in Fayetteville.

[14] Despite Vance's intervention, at least 125 of the 558 convicts died because of inclement weather, inadequate housing, lack of food, and dangerous working conditions such as the cave-ins and accidents at the Swannanoa Tunnel that killed 21 people.

[12] He also said, "To suppose the States are either unable, unwilling, or too corrupt to hold peaceful and honest elections, is to declare unmistakably that the people therein are incapable of self-government...For one, I can say, with unspeakable pride and absolute truth, that the people of North Carolina who sent me here are able, willing, and virtuous enough to fulfill these and all other higher functions of government; that they have ever done so since the keels of Raleigh's ships first grated upon the white sands of her shores; and God helping them, they and their children will continue to do so, if not destroyed by centralization..."[12] Vance also supported the Blair Education Bill which requested federal funding to help educate the freed slaves in the South.

[12] In a speech on January 30, 1890, regarding Senate Bill 1121, which authorized people of color to emigrate from Southern states, Vance came close to speaking against slavery, saying, "Those of us in the South who had deprecated the war and deplored the agitation which led to it, as we sat in the ashes of our own homes and scraped ourselves with potsherds of desolation, yet consoled ourselves for the slaughter of our kindred and the devastation of our fields by the reflection that this, at least, was the end; that the great original wrong committed by our fathers had at last been atoned for...."[12] [emphasis added] Nonetheless, Vance's racial views showed when he talked about Reconstruction.

Vance also outlined his vision of the future, with a bit of sarcasm:The millennium has not yet arrived in the land of reconstruction; the reign of perfect righteousness, of absolute justice, has not yet been established south of Mason and Dixon's line, though of course, it is in full operation north of that imaginary division.

[12] Later, he introduced Senate Bill 2806, aka the sub-treasury scheme, at the request of North Carolina's first Commissioner of Agriculture, Leonidas L. Polk, who had become president of the National Farmers' Alliance and Industrial Union.

[12] When the North Carolina legislature stated that their appointed Senator for the 1891 term should vote for the sub-treasury scheme, Vance "positively and emphatically declined" to agree to be elected under such constraints.

"[12] Vance, who was dealing with poor health at the time, wrote a letter, rather than speaking in public, about the need for Democrats to fight the Republicans who want to limit rights given by the Constitution.

But an individual preference before the nomination of a candidate is one thing and the duty of a true man after that nomination has been fairly made is another and very different thing indeed...If we refuse to abide by the voice of the majority of our fellow Democrats, freely and unmistakably expressed in friendly convention, there is an end of all associated party effort in the government of our country; if we personally participate in that...convention and then refuse to abide by the decision of its tribunal...then there is an end of all personal honor among all men, and the confidence which is necessary to all combined efforts is forever gone.

[12] Vance made his last speech in the Senate on September 1, 1893, speaking against House Bill 1, regarding the unconditional repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act that was approved in 1890.

"[12] Following the Civil War, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) emerged as an organization that engaged in terrorism and intimidation throughout the South, including North Carolina.

Hope of Lincoln County, North Carolina, submitted to the US Congress's Joint Select Committee to Inquire into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States, which published its report in 1872.

[58][45] Modern experts note other discrepancies in Authentic History, including fabricated descriptions of Klan costumes, giving reason to question any claims she made about Vance.

[26][4] After he had passed the Bar and started a law practice, Vance married Harriett at Quaker Meadows, the home of her uncle Charles McDowell in Burke County, North Carolina on August 3, 1853.

[12][71] Thousands of people lined the railroad tracks "to pay their last respects to one whom they loved and admired very much" as the funeral train headed south and west and stopped at towns and cities such as Richmond, Danville, Greensboro, Durham, and Raleigh.

[16] Surviving members of Vance's Rough and Ready Guard led a procession of 710 carriages from the church to Riverside Cemetery where nearly 10,000 mourners attended his funeral and burial, including people he formerly enslaved.

It's fair to say, though, that his legacy is that he set the stage for North Carolina to be perceived as at least somewhat more racially tolerant and culturally progressive than its Deep South neighbors, a tradition that held through the 20th–century and beyond until quite recently.