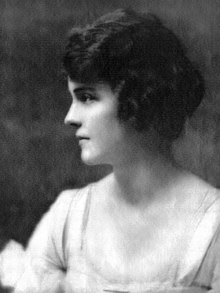

Zelda Fitzgerald

[10] While institutionalized at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, she authored the 1932 novel Save Me the Waltz, a semi-autobiographical account of her early life in the American South during the Jim Crow era and her marriage to F. Scott Fitzgerald.

[42][43] An outspoken advocate of lynching who served six terms in the United States Senate, Morgan played a key role in laying the foundation for the Jim Crow era in the American South.

[52] She developed an appetite for attention, actively seeking to flout convention, whether by dancing or by wearing a tight, flesh-colored bathing suit to fuel rumors that she swam nude.

"[65] In addition to inspiring the character of Rosalind Connage, Scott used a quote from Zelda's letters for a soliloquy by the narrator at the conclusion of The Romantic Egotist, later retitled and published as This Side of Paradise.

[63] While dating Zelda and other women in Montgomery, Scott received a letter from Ginevra King informing him of her impending arranged marriage to polo player William "Bill" Mitchell.

[84] However, when Scott's attempts to become a published author faltered during the next four months, Zelda became convinced that he could not support her accustomed lifestyle, and she broke off the engagement during the Red Summer of 1919.

[85][86] Having been rejected by both Zelda and Ginevra during the past year due to his lack of financial prospects, Scott suffered from intense despair,[87] and he carried a revolver daily while contemplating suicide.

[89] Abstaining from alcohol and parties,[90] he worked day and night to revise The Romantic Egotist as This Side of Paradise—an autobiographical account of his Princeton years and his romances with Ginevra, Zelda, and others.

"[63] Zelda agreed to marry Scott once Scribner's published the novel;[82] in turn, Fitzgerald promised to bring her to New York with "all the iridescence of the beginning of the world.

[111] Zelda's parents visited their Westport cottage soon after, but her father Judge Anthony Sayre took a dim view of the couples' constant partying and scandalous lifestyle.

[131] Zelda's thoughts on terminating her second pregnancy are unknown, but in the first draft of The Beautiful and Damned, Scott wrote a scene in which Gloria Gilbert believes she is pregnant and Anthony Patch suggests she "talk to some woman and find out what's best to be done.

"[132] Anthony's suggestion was removed from the final version, and this significant alteration shifted the focus from a moral dilemma about the act of abortion to Gloria's superficial concern that a baby would ruin her figure.

[134] During this period, while Scott wrote short stories at home, the New York Police Department detained Zelda near the Queensboro Bridge on the suspicion of her being the "Bobbed Haired Bandit," an infamous spree-robber later identified as Celia Cooney.

[7] On his part, Jozan dismissed the entire story as pure fabrication and claimed that no romance with Zelda had ever occurred: "They both had a need of drama, they made it up and perhaps they were the victims of their own unsettled and a little unhealthy imagination.

"[139] The incident likely influenced Fitzgerald's writing of The Great Gatsby, and he drew upon many elements of his tempestuous relationship with Zelda, including the loss of certainty in her love.

[146] In August, he wrote to his friend Ludlow Fowler: "I feel old too, this summer ... the whole burden of this novel—the loss of those illusions that give such color to the world that you don't care whether things are true or false as long as they partake of the magical glory.

Disliking Fitzgerald's chosen title of Trimalchio in West Egg, editor Max Perkins persuaded him that the reference was too obscure and that people would be unable to pronounce it.

[154] In his memoir A Moveable Feast, Hemingway claims he realized that Zelda had a mental illness when she insisted that jazz singer Al Jolson was greater than Jesus Christ.

"[187] Despite her being far too old to achieve such an ambition, Scott Fitzgerald paid for Zelda to begin practicing under the tutelage of Catherine Littlefield, director of the Philadelphia Opera Ballet.

"[118] According to Zelda's daughter, although Scott "greatly appreciated and encouraged his wife's unusual talents and ebullient imagination,"[123] he became alarmed when her "dancing became a twenty-four-hour preoccupation which was destroying her physical and mental health.

[191] In October 1929, during an automobile trip to Paris along the mountainous roads of the Grande Corniche, Zelda seized the car's steering wheel and tried to kill herself, her husband, and her nine-year-old daughter, Scottie, by driving over a cliff.

[193] The clinic primarily treated gastrointestinal ailments, and, due to her profound psychological problems, she was moved again to a psychiatric facility in Prangins on the shores of Lake Geneva on June 5, 1930.

[197] On February 12, 1932, over her husband's objections,[198] Fitzgerald was admitted by The Henry Phipps Psychiatric Clinic at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, where her treatment was overseen by Dr. Adolf Meyer, an expert on schizophrenia.

[212] On October 7, 1932, Scribner's published Save Me the Waltz with a printing of 3,010 copies—not unusually low for a first novel in the middle of the Great Depression—on cheap paper, with a cover of green linen.

The parallels to the Fitzgeralds were obvious: The protagonist of the novel is Alabama Beggs—like Zelda, the daughter of a Southern judge—who marries David Knight, an aspiring painter who abruptly becomes famous for his work.

In 1936, Scott placed her in the Highland Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina, writing to friends:[226] Zelda now claims to be in direct contact with Christ, William the Conqueror, Mary Stuart, Apollo and all the stock paraphernalia of insane-asylum jokes ... For what she has really suffered, there is never a sober night that I do not pay a stark tribute of an hour to in the darkness.

In 1950, acquaintance and screenwriter Budd Schulberg wrote The Disenchanted, with characters based recognizably on the Fitzgeralds who end up as forgotten former celebrities, he awash with alcohol and she befuddled by mental illness.

"[249] However, in the wake of Milford's biography, a new perspective emerged,[26] and scholar Jacqueline Tavernier-Courbin wrote in 1979: "Save Me the Waltz is a moving and fascinating novel which should be read on its own terms equally as much as Tender Is the Night.

"[249] After Milford's 1970 biography, Save Me the Waltz became the focus of many literary studies that explored different aspects of her work: how the novel contrasted with Scott's depiction of their marriage in Tender Is the Night,[25] and how the consumer culture that emerged in the 1920s placed stress on modern women.

A review of the exhibition by curator Everl Adair noted the influence of Vincent van Gogh and Georgia O'Keeffe on her paintings and concluded that her surviving corpus of art "represents the work of a talented, visionary woman who rose above tremendous odds to create a fascinating body of work—one that inspires us to celebrate the life that might have been.