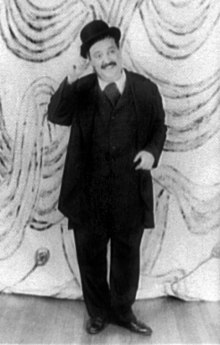

Zero Mostel

He showed an intelligence and perception which convinced his father he had the makings of a rabbi,[13] but Zero preferred painting and drawing, a passion he retained for life.

According to Roger Butterfield, Zero's mother sent him to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to copy paintings while dressed in a velvet suit.

Zero had a favorite painting, John White Alexander's Study in Black and Green, which he copied every day, to the delight of the gallery crowds.

The marriage did not last, however, since Clara could not accept the many hours Mostel spent in his studio with his fellow artists, and he did not seem to be able to provide for her at the level to which she had been accustomed.

[16] Part of Mostel's duty with the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) was to give gallery talks at New York's museums.

[citation needed] In 1941, the Café Society, a downtown Manhattan nightclub, hired Mostel as a professional comedian to play regularly there, where he adopted the stage name Zero.

Although he gave varying accounts of his Army service, records show he was honorably discharged in August 1943 because of an unspecified physical disability.

[18] Mostel married Kathryn (Kate) Cecilia Harkin, an actress and dancer, on July 2, 1944, after two years of courtship.

[23] It was not until 1950 that Mostel again acted in movies, for a role in the Oscar-winning film Panic in the Streets, at the request of its director, Elia Kazan.

Kazan describes his attitude and feelings during that period, where Mostel played supporting roles in five movies for Twentieth Century Fox in 1950, all in films released in 1951.

[25] On January 29, 1952, Martin Berkeley identified Mostel to the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) as having been a member of the Communist Party.

During this period he also appeared in many regional productions of shows like Peter Pan (as Captain Hook) and Kismet (as the Wazir), with his name seen prominently in the advertising.

In 1957, Toby Cole, a New York theatrical agent who strongly opposed the blacklist, contacted Mostel and asked to represent him.

[28] On January 13, 1960, while exiting a taxi on his way back from rehearsals for the play The Good Soup, Mostel was hit by a number 18 (now the M86) 86th Street crosstown bus, and his leg was crushed.

His transition onstage from man to rhinoceros became a thing of legend; he won his first Tony Award for Best Actor, even though he was not in the lead role.

The reviews were excellent, and, after a few slow weeks after which the play was partially rewritten with a new opening song, "Comedy Tonight", which became the play's most popular piece, the show became a great commercial success, running 964 performances and conferring star status on Mostel (he also won a Tony Award for Best Actor in a Musical for this role).

Because of Mostel's respect for the works of Sholem Aleichem he insisted that more of the author's mood and style be incorporated into the musical, and he made major contributions to its shape.

Mostel received a Tony Award for it and was invited to a reception in the White House, officially ending his status as a political pariah.

Reflecting on that rising popularity, Roger Ebert, longtime critic for the Chicago Sun-Times, wrote in 2000, "This is one of the funniest movies ever made", adding that Mostel's performance "is a masterpiece of low comedy.

"[31] He lived in a large rented apartment in The Belnord on the Upper West Side of Manhattan and built a summer house on Monhegan Island in Maine.

[32] In his last decade, Mostel's star dimmed as he appeared in movies that were received with indifference by both critics and the general audience.

His more notable films in these years include the movie version of Rhinoceros (appearing with his Producers costar Gene Wilder), The Hot Rock and The Front (where he played Hecky Brown, a blacklisted performer whose story bears a similarity to Mostel's own, and for which he was nominated for a BAFTA Award for Best Supporting Actor).

Screenwriter Walter Bernstein loosely based the character of Hecky Brown on television actor Philip Loeb, who was a friend of Mostel.

[33] On Broadway, he starred in revivals of Ulysses in Nighttown (receiving a Tony nomination for Best Actor) and Fiddler on the Roof.

He also made memorable appearances in children's shows such as Sesame Street, The Electric Company (for which he performed the Spellbinder in the Letterman cartoons), and gave voice to the boisterous seagull Kehaar in the animated film Watership Down.

Norman Jewison stated this as a reason for preferring Chaim Topol for the role of Tevye in the movie version of Fiddler on the Roof.

[38]Other producers, such as Jerome Robbins and Hal Prince, preferred to hire Mostel on short contracts, knowing that he would become less faithful to the script as time went on.

His exuberant personality, though largely responsible for his success, had also intimidated others in his profession and prevented him from receiving some important roles.

[citation needed] In his autobiography Kiss Me Like a Stranger, actor Gene Wilder describes being initially terrified of Mostel.

The play recounts events from Mostel's life and career, including his HUAC testimony, his professional relationships, and his theatrical work.