No-till farming

[2] While no-till is agronomically advantageous and results in higher yields, farmers wishing to adapt the system face a number of challenges.

Established farms may have to face a learning curve, buy new equipment, and deal with new field conditions.

[3][4] Perhaps the biggest impediment, especially for grains, is that farmers can no longer rely on the mechanical pest and weed control that occurs when crop residue is buried to significant depths.

No-till farmers must rely on chemicals, biological pest control, cover cropping, and more intensive management of fields.

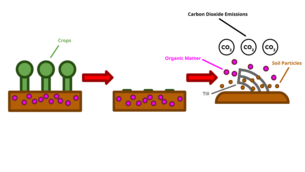

Tillage is the agricultural preparation of soil by mechanical agitation, typically removing weeds established in the previous season.

The first adopters of no-till include Klingman (North Carolina), Edward Faulkner, L. A. Porter (New Zealand), Harry and Lawrence Young (Herndon, Kentucky), and the Instituto de Pesquisas Agropecuarias Meridional (1971 in Brazil) with Herbert Bartz.

No-till management results in fewer passes with equipment, and the crop residue prevents evaporation of rainfall and increases water infiltration into the soil.

[18] By 2023, farmland with strict no-tillage principles comprise roughly 30% of the cropland in the U.S.[19] As of 2020, an estimated 7% of English arable land was being cultivated using no-till farming.

[20] The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) offers incentives to farmers to convert to no-till farming, such as a payment of £73 per hectare of land eligible for this scheme.

[26] Another possible benefit is that because of the higher water content, instead of leaving a field fallow it can make economic sense to plant another crop instead.

[27] A problem with no-till farming is that the soil warms and dries more slowly in spring, which may delay planting.

The slower warming is due to crop residue being a lighter color than the soil exposed in conventional tillage, which absorbs less solar energy.

[28] Another problem with no-till farming is that if production is impacted negatively by the implemented process, the practice's profitability may decrease with increasing fuel prices and high labor costs.

[29] In spring, poor draining clay soil may have lower production due to a cold and wet year.

[30] The economic and ecological benefits of implementing no-till practices can require sixteen to nineteen years.

A combination of techniques, equipment, pesticides, crop rotation, fertilization, and irrigation have to be used for local conditions.

[citation needed] On some crops, like continuous no-till corn, the residue's thickness on the field's surface can become problematic without proper preparation and equipment.

[35] Faster growing weeds can be reduced by increased competition with eventual growth of perennials, shrubs and trees.

The use of herbicides is not strictly necessary, as demonstrated in natural farming, permaculture, and other practices related to sustainable agriculture.

H.R.2508 is also backed by two other representatives from high agricultural states, Rep. Eric A. Crawford of Arkansas and Rep. Don Bacon of Nebraska.

[47] Farmers within the U.S. are encouraged through subsidies and other programs provided by the government to meet a defined level of tillage conservation.

[50] Efforts are put out to help reduce the amount of contamination from the agricultural industry as well as increasing the health of the soil.

[58][59] Nitrous oxide is a potent greenhouse gas, 300 times stronger than CO2, and stays in the atmosphere for 120 years.

The potential for global cooling as a result of increased albedo in no-till croplands is similar in magnitude to other biogeochemical carbon sequestration processes.