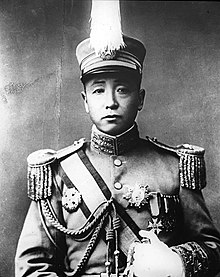

Zhang Zuolin

Zhang was born in 1875 in Haicheng (now PanJin),[1] a county in southern Fengtian province (modern Liaoning) in northeastern China, to poor parents.

At the end of the Qing dynasty Zhang managed to have his men recognised as a regiment of the regular Chinese army, patrolling the borders of Manchuria and suppressing other bandit gangs.

[2] The American surgeon Louis Livingston Seaman met Zhang during the Russo-Japanese War, and took several photographs of him and his troops as well as writing an account of his journey.

[7][8] During the 1911 Xinhai Revolution some military commanders wanted to declare independence for Manchuria; but the pro-Manchu governor used Zhang's regiment to set up a "Manchurian People's Peacekeeping Council", intimidating would-be rebels and revolutionaries.

Yuan Shikai, operating out of Beijing, sent other northern military commanders a series of telegrams, advising them to oppose Sun's administration.

Zhang then murdered a number of leading figures in his base city of Shenyang (then known as "Mukden"), and was rewarded with a series of impressive-sounding titles by the nearly defunct Qing court.

After Yuan died in June 1916, the new central government named Zhang both military and civil governor of Liaoning, the essential components of a successful warlord.

Zhang sought good relations with Puyi in order to increase his power and cement his legitimacy if a restoration was ever attempted.

He began to surround himself in luxury, building a chateau-style home near Shenyang, and had at least five wives (an accepted practice of any powerful or wealthy Chinese at the time).

It had obtained large stocks of weapons left over from World War I and included naval units, an air force and an armaments industry.

Zhang integrated a large number of local militias into his army, and thus prevented Manchuria from falling into the chaos which reigned in China proper at the time.

Only postal and customs revenues continued to be sent to Beijing, because they had been pledged to the victorious foreign powers after the failed Boxer Rebellion of 1900, and Zhang feared their intervention.

From 1917 to about 1924 the new Communist government in Moscow was having such difficulties establishing itself in Siberia that often it was not clear who was in charge of operating the railway on the Russian side.

The situation's precariousness was demonstrated by an outbreak of pneumonic plague in Hailar, a town at the western end of the Chinese Eastern Railway, in October 1920.

[clarification needed] The soldiers freed some of their comrades who had been imprisoned as contacts, and they escaped to the mining town of Dalainor on the Amur River, where a quarter of the population died.

Lu Zhankui, a Mongol officer under Zhang, was instrumental in bringing Oomoto leader Onisaburo Deguchi, and Aikido founder Morihei Ueshiba, to Mongolia in 1924.

[citation needed] He had inherited a financially weak provincial government—in 1917 Fengtian faced ten outstanding loans from foreign-controlled consortia and banks totaling over 12 million yuan.

Zhang chose Wang Yongjiang, who had served as head of a regional tax office, for the task of solving Fengtian's financial problems.

A number of currencies were circulating in the province, as was the custom in China, and the paper notes issued by the provincial government had experienced a steady depreciation in value.

Much to the surprise of the Chinese, the new currency even gained in value against the gold yen, although Japanese businessmen claimed that it was not backed up by sufficient silver reserves.

In 1919 France had left Renault FT tanks in Vladivostok after the joint Allied intervention,[20] and Zhang Zuolin soon incorporated them into the Manchurian Army.

In the summer of 1920, Zhang made a foray into North China on the other side of the Great Wall, trying to topple Duan Qirui, the leading warlord of Beijing.

In December 1921, Zhang visited Beijing; at his request, the entire cabinet, led by Jin Yunpeng, resigned, leaving him free to appoint a new government.

In the spring of 1922, Zhang personally took the position of Commander-in-Chief of the Fengtian Army, and on April 19 his forces entered China proper.

As an incentive, they were made eligible for reduced fares on all Chinese-owned railways in Manchuria, received funds to build dwellings and were promised total ownership after five years of continuous occupation.

An especially ambitious project was to break the Japanese monopoly on cotton textiles by creating a large mill which, much to Japan's sorrow, succeeded.

After the disastrous defeat of 1922, Zhang had reorganized his Fengtian Army, started a training program, and bought new equipment, including mobile radios and machine guns.

However, the military situation was so unstable that Sun Chuanfang, a Zhili clique warlord whose sphere of influence extended along the Yangtze, managed to push back the Fengtian Army again.

An extremely serious crisis erupted in November 1925, when Guo Songling revolted and ordered his troops to turn back and march on Shenyang.

In addition, Japan applied pressure on Zhang to leave Beijing and to return to Manchuria and underscored that by bringing reinforcements to Tianjin.